Imaging reveals how microplastics may harm the brain

Pollution from microplastics – small plastic particles less than 5 mm in size – poses an ongoing threat to human health. Independent studies have found microplastics in human tissues and within the bloodstream. And as blood circulates throughout the body and through vital organs, these microplastics reach can critical regions and lead to tissue dysfunction and disease. Microplastics can also cause functional irregularities in the brain, but exactly how they exert neurotoxic effects remains unclear.

A research collaboration headed up at the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences and Peking University has shed light on this conundrum. In a series of cerebral imaging studies reported in Science Advances, the researchers tracked the progression of fluorescent microplastics through the brains of mice. They found that microplastics entering the bloodstream become engulfed by immune cells, which then obstruct blood vessels in the brain and cause neurobehavioral abnormalities.

“Understanding the presence and the state of microplastics in the blood is crucial. Therefore, it is essential to develop methods for detecting microplastics within the bloodstream,” explains principal investigator Haipeng Huang from Peking University. “We focused on the brain due to its critical importance: if microplastics induce lesions in this region, it could have a profound impact on the entire body. Our experimental technology enables us to observe the blood vessels within the brain and detect microplastics present in these vessels.”

In vivo imaging

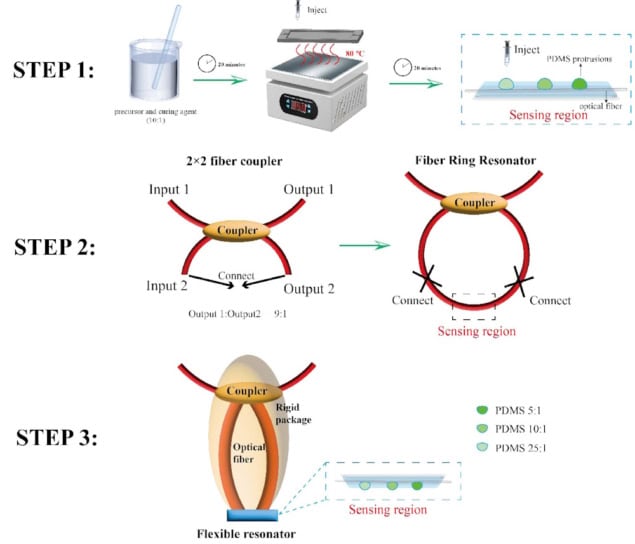

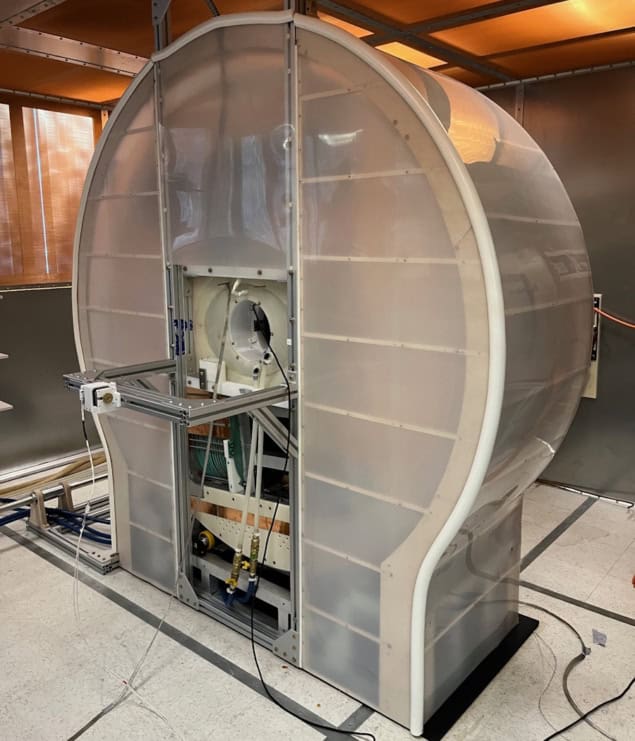

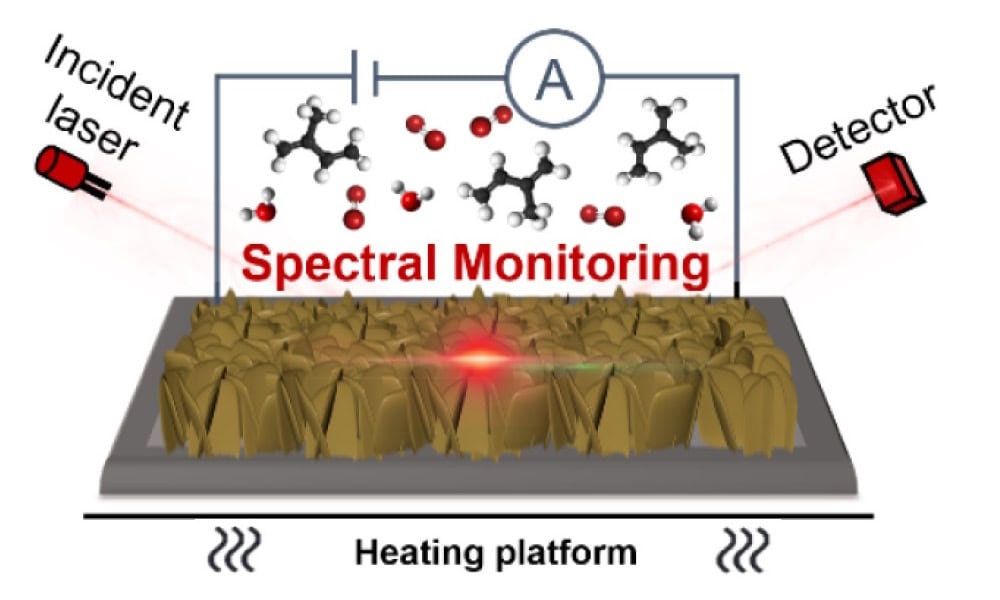

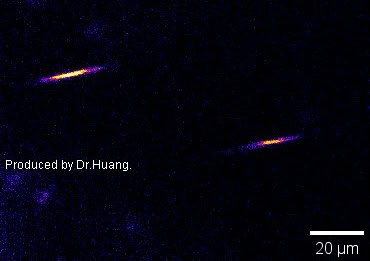

Huang and colleagues developed a microplastics imaging system by integrating a two-photon microscopy system with fluorescent plastic particles and demonstrated that it could image brain blood vessels in awake mice. They then fed five mice with water containing 5-µm diameter fluorescent microplastics. After a couple of hours, fluorescence images revealed microplastics within the animals’ cerebral vessels.

As they move through rapidly flowing blood, the microplastics generate a fluorescence signal resembling a lightning bolt, which the researchers call a “microplastic flash” (MP-flash). This MP-flash was observed in four of the mice, with the entire MP-flash trajectory captured in a single imaging frame of less than 208 ms.

Three hours after administering the microplastics, the researchers observed fluorescent cells in the bloodstream. The signals from these cells were of comparable intensity to the MP-flash signal, suggesting that the cells had engulfed microplastics in the blood to create microplastic-labelled cells (MPL-cells). The team note that the microplastics did not directly attach to the vessel wall or cross into brain tissue.

To test this idea further, the researchers injected microplastics directly into the bloodstream of the mice. Within minutes, they saw the MP-Flash signal in the brain’s blood vessels, and roughly 6 min later MPL-cells appeared. No fluorescent cells were seen in non-treated mice. Flow cytometry of mouse blood after microplastics injection revealed that the MPL-cells, which were around 21 µm in dimeter, were immune cells, mostly neutrophils and macrophages.

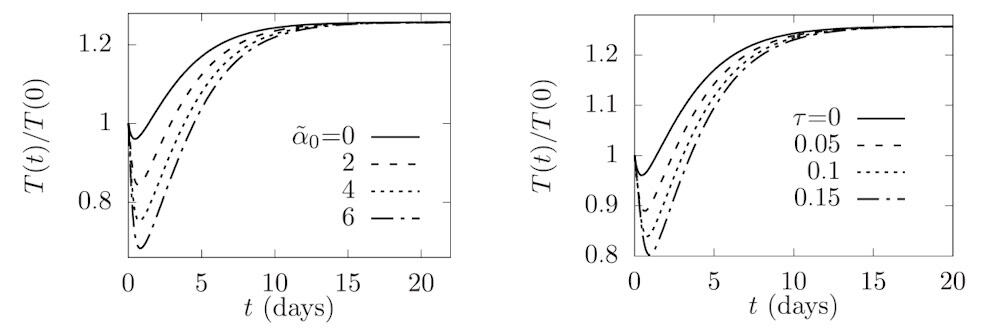

Tracking these MPL-cells revealed that they sometimes became trapped within a blood vessel. Some cells exited the imaging field following a period of obstruction while others remained in cerebral vessels for extended durations, in some instances for nearly 2.5 h of imaging. The team also found that one week after injection, the MPL-cells had still not cleared, although the density of blockages was much reduced.

“[While] most MPL-cells flow rapidly with the bloodstream, a small fraction become trapped within the blood vessels,” Huang tells Physics World. “We provide an example where an MPL-cell is trapped at a microvascular turn and, after some time, is fortunate enough to escape. Many obstructed cells are less fortunate, as the blockage may persist for several weeks. Obstructed cells can also trigger a crash-like chain reaction, resulting in several MPL-cells colliding in a single location and posing significant risks.”

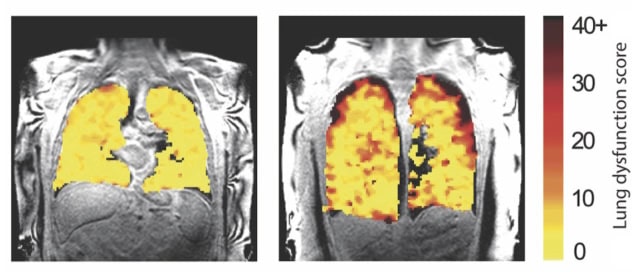

The MPL-cell blockages also impeded blood flow in the mouse brain. Using laser speckle contrast imaging to monitor blood flow, the researchers saw reduced perfusion in the cerebral cortical vessels, notably at 30 min after microplastics injection and particularly affecting smaller vessels.

Changing behaviour

Lastly, Huang and colleagues investigated whether the reduced blood supply to the brain caused by cell blockages caused behavioural changes in the mice. In an open-field experiment (used to assess rodents’ exploratory behaviour) mice injected with microplastics travelled shorter distances at lower speeds than mice in the control group.

The Y-maze test for assessing memory also showed that microplastics-treated mice travelled smaller total distances than control animals, with a significant reduction in spatial memory. Tests to evaluate motor coordination and endurance revealed that microplastics additionally inhibited motor abilities. By day 28 after injection, these behavioural impairments were restored, corresponding with the observed recovery of MPL-cell obstruction in the cerebral vasculature at 28 days.

The researchers conclude that their study demonstrates that microplastics harm the brain indirectly – via cell obstruction and disruption of blood circulation – rather than directly penetrating tissue. They emphasize, however, that this mechanism may not necessarily apply to humans, who have roughly 1200 times greater volume of circulating blood volume than mice and significantly different vascular diameters.

“In the future, we plan to collaborate with clinicians,” says Huang. “We will enhance our imaging techniques for the detection of microplastics in human blood vessels, and investigate whether ‘MPL-cell-car-crash’ happens in human. We anticipate that this research will lead to exciting new discoveries.”

Huang emphasizes how the use of fluorescent microplastic imaging technology has fundamentally transformed research in this field over the past five years. “In the future, advancements in real-time imaging of depth and the enhanced tracking ability of microplastic particles in vivo may further drive innovation in this area of study,” he says.

The post Imaging reveals how microplastics may harm the brain appeared first on Physics World.