Dix ans après, un accord de Paris aux résultats mitigés

China has delayed the return of a crewed mission to the country’s space station over fears that the astronaut’s spacecraft has been struck by space debris. The craft was supposed to return to Earth on 5 November but the China Manned Space Agency says it will now carry out an impact analysis and risk assessment before making any further decisions about when the astronauts will return.

The Shenzhou programme involves taking astronauts to and from China’s Tiangong space station, which was constructed in 2022, for six-month stays.

Shenzhou-20, carrying three crew, launched on 24 April from Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center on board a Long March 2F rocket. Once docked with Tiangong the three-member crew of Shenzhou-19 began handing over control of the station to the crew of Shenzhou-20 before they returned to Earth on 30 April.

The three-member crew of Shenzhou-21 launched on 31 October and underwent the same hand-over process with the crew of Shenzhou-20 before they were set to return to Earth on Wednesday.

Yet pre-operation checks revealed that the craft had been hit by “a small piece of debris” with the location and scale of the damage to Shenzhou-20 having not been released.

If the craft is deemed unsafe following the assessment, it is possible that the crew of Shenzhou-20 will return to Earth aboard Shenzhou-21. Another option is to launch a back-up Shenzhou spacecraft, which remains on stand-by and could be launched within eight days.

Space debris is of increasing concern and this marks the first time that a crewed craft has been delayed due to a potential space debris impact. In 2021, for example, China noted that Tiangong had to perform two emergency avoidance manoeuvres to avoid fragments produced by Starlink satellites that were launched by SpaceX.

The post China’s Shenzhou-20 crewed spacecraft return delayed by space debris impact appeared first on Physics World.

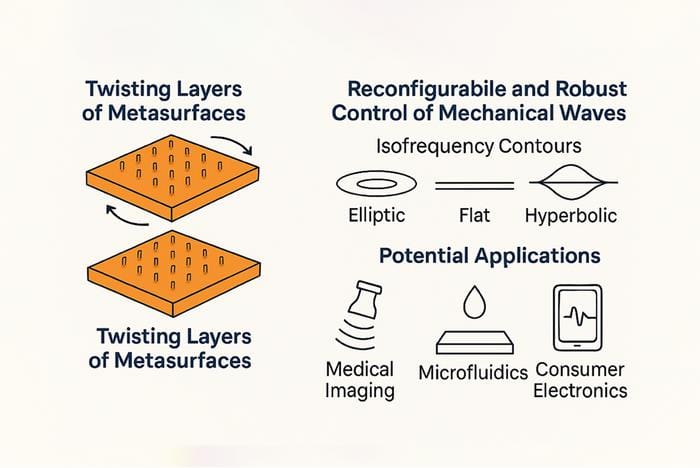

By simply placing two identical elastic metasurfaces atop each other and then rotating them relative to each other, the topology of the elastic waves dispersing through the resulting stacked structure can be changed – from elliptic to hyperbolic. This new control technique, from physicists at the CUNY Advanced Science Research Center in the US, works over a broad frequency range and has been dubbed “twistelastics”. It could allow for advanced reconfigurable phononic devices with potential applications in microelectronics, ultrasound sensing and microfluidics.

The researchers, led by Andrea Alù, say they were inspired by the recent advances in “twistronics” and its “profound impact” on electronic and photonic systems. “Our goal in this work was to explore whether similar twist-induced topological phenomena could be harnessed in elastodynamics in which phonons (vibrations of the crystal lattice) play a central role,” says Alù.

In twistelastics, the rotations between layers of identical, elastic engineered surfaces are used to manipulate how mechanical waves travel through the materials. The new approach, say the CUNY researchers, allows them to reconfigure the behaviour of these waves and precisely control them. “This opens the door to new technologies for sensing, communication and signal processing,” says Alù.

In their work, the researchers used computer simulations to design metasurfaces patterned with micron-sized pillars. When they stacked one such metasurface atop the other and rotated them at different angles, the resulting combined structure changed the way phonons spread. Indeed, their dispersion topology went from elliptic to hyperbolic.

At a specific rotation angle, known as the “magic angle” (just like in twistronics), the waves become highly focused and begin to travel in one direction. This effect could allow for more efficient signal processing, says Alù, with the signals being easier to control over a wide range of frequencies.

The new twistelastic platform offers broadband, reconfigurable, and robust control over phonon propagation,” he tells Physics World. “This may be highly useful for a wide range of application areas, including surface acoustic wave (SAW) technologies, ultrasound imaging and sensing, microfluidic particle manipulation and on-chip phononic signal processing.

Since the twist-induced transitions are topologically protected, again like in twistronics, the system is resilient to fabrication imperfections, meaning it can be miniaturized and integrated into real-world devices, he adds. “We are part of an exciting science and technology centre called ‘New Frontiers of Sound’, of which I am one of the leaders. The goal of this ambitious centre is to develop new acoustic platforms for the above applications enabling disruptive advances for these technologies.”

Looking ahead, the researchers say they are looking into miniaturizing their metasurface design for integration into microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). They will also be studying multi-layer twistelastic architectures to improve how they can control wave propagation and investigating active tuning mechanisms, such as electromechanical actuation, to dynamically control twist angles. “Adding piezoelectric phenomena for further control and coupling to the electromagnetic waves,” is also on the agenda says Alù.

The present work is detailed in PNAS.

The post Twistelastics controls how mechanical waves move in metamaterials appeared first on Physics World.

Researchers in China claim to have made the first ever room-temperature superconductor by compressing an alloy of lanthanum-scandium (La-Sc) and the hydrogen-rich material ammonia borane (NH3BH3) together at pressures of 250–260 GPa, observing superconductivity with a maximum onset temperature of 298 K. While these high pressures are akin to those at the centre of the Earth, the work marks a milestone in the field of superconductivity, they say.

Superconductors conduct electricity without resistance and many materials do this when cooled below a certain transition temperature, Tc. In most cases this temperature is very low – for example, solid mercury, the first superconductor to be discovered, has a Tc of 4.2 K. Researchers have therefore been looking for superconductors that operate at higher temperatures – perhaps even at room temperature. Such materials could revolutionize a host of application areas, including increasing the efficiency of electrical generators and transmission lines through lossless electricity transmission. They would also greatly simplify technologies such as MRI, for instance, that rely on the generation or detection of magnetic fields.

Researchers made considerable progress towards this goal in the 1980s and 1990s with the discovery of the “high-temperature” copper oxide superconductors, which have Tc values between 30 and 133 K. Fast-forward to 2015 and the maximum known critical temperature rose even higher thanks to the discovery of a sulphide material, H3S, that has a Tc of 203 K when compressed to pressures of 150 GPa.

This result sparked much interest in solid materials containing hydrogen atoms bonded to other elements and in 2019, the record was broken again, this time by lanthanum decahydride (LaH10), which was found to have a Tc of 250–260 K, albeit again at very high pressures. Then in 2021, researchers observed high-temperature superconductivity in the cerium hydrides, CeH9 and CeH10, which are remarkable because they are stable and boast high-temperature superconductivity at lower pressures (about 80 GPa, or 0.8 million atmospheres) than the other so-called “superhydrides”.

In recent years, researchers have started turning their attention to ternary hydrides – substances that comprise three different atomic species rather than just two. Compared with binary hydrides, ternary hydrides are more structurally complex, which may allow them to have higher Tc values. Indeed, Li2MgH16 has been predicted to exhibit “hot” superconductivity with a Tc of 351–473 K under multimegabar pressures and several other high-Tc hydrides, including MBxHy, MBeH8 and Mg2IrH6-7, have been predicted to be stable under comparatively lower pressures.

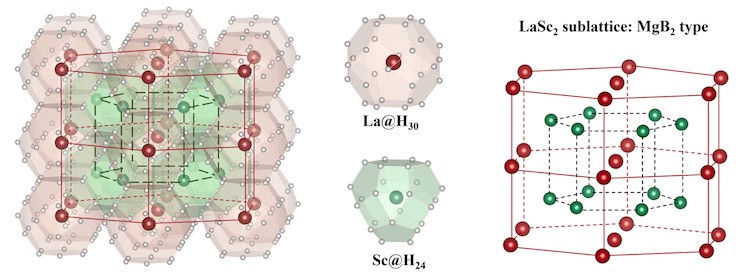

In the new work, a team led by physicist Yanming Ma of Jilin University, studied LaSc2H24 – a compound that’s made by doping Sc into the well-known La-H binary system. Ma and colleagues had already predicted in theory – using the crystal structure prediction (CALYPSO) method – that this ternary material should feature a hexagonal P6/mmm symmetry. Introducing Sc into the La-H results in the formation of two novel interlinked H24 and H30 hydrogen clathrate “cages” with the H24 surrounding Sc and the H30 surrounding La.

The researchers predicted that these two novel hydrogen frameworks should produce an exceptionally large hydrogen-derived density of states at the Fermi level (the highest energy level that electrons can occupy in a solid at a temperature of absolute zero), as well as enhancing coupling between electrons and phonons (vibrations of the crystal lattice) in the material, leading to an exceptionally high Tc of up to 316 K at high pressure.

To characterize their material, the researchers placed it in a diamond-anvil cell, a device that generates extreme pressures as it squeezes the sample between two tiny, gem-grade crystals of diamond (one of the hardest substances known) while heating it with a laser. In situ X-ray diffraction experiments revealed that the compound crystallizes into a hexagonal structure, in excellent agreement with the predicted P6/mmm LaSc2H24 structure.

A key piece of experimental evidence for superconductivity in the La-Sc-H ternary system, says co-author Guangtao Liu, came from measurements that repeatedly demonstrated the onset of zero electrical resistance below the Tc.

Another significant proof, Liu adds, is that the Tc decreases monotonically with the application of an external magnetic field in a number of independently synthesized samples. “This behaviour is consistent with the conventional theory of superconductivity since an external magnetic field disrupts Cooper pairs – the charge carriers responsible for the zero-resistance state – thereby suppressing superconductivity.”

“These two main observations demonstrate the superconductivity in our synthesized La-Sc-H compound,” he tells Physics World.

The experiments were not easy, Liu recalls. The first six months of attempting to synthesize LaSc2H24 below 200 GPa yielded no obvious Tc enhancement. “We then tried higher pressure and above 250 GPa, we had to manually deposit three precursor layers and ensure that four electrodes (for subsequent conductance measurements) were properly connected to the alloy in an extremely small sample chamber, just 10 to 15 µm in size,” he says. “This required hundreds of painstaking repetitions.”

And that was not all: to synthesize the LaSc2H24, the researchers had to prepare the correct molar ratios of a precursor alloy. The Sc and La elements cannot form a solid solution because of their different atomic radii, so using a normal melting method makes it hard to control this ratio. “After about a year of continuous investigations, we finally used the magnetron sputtering method to obtain films of LaSc2H24 with the molar ratios we wanted,” Liu explains. “During the entire process, most of our experiments failed and we ended up damaging at least 70 pairs of diamonds.”

Sven Friedemann of the University of Bristol, who was not involved in this work, says that the study is “an important step forward” for the field of superconductivity with a new record transition temperature of 295 K. “The new measurements show zero resistance (within resolution) and suppression in magnetic fields, thus strongly suggesting superconductivity,” he comments. “It will be exciting to see future work probing other signatures of superconductivity. The X-ray diffraction measurements could be more comprehensive and leave some room for uncertainty to whether it is indeed the claimed LaSc2H24 structure giving rise to the superconductivity.”

Ma and colleagues say they will continue to study the properties of this compound – and in particular, verify the isotope effect (a signature of conventional superconductors) or measure the superconducting critical current. “We will also try to directly detect the Meissner effect – a key goal for high-temperature superhydride superconductors in general,” says Ma. “Guided by rapidly advancing theoretical predictions, we will also synthesize new multinary superhydrides to achieve better superconducting properties under much lower pressures.”

The study is available on the arXiv pre-print server.

The post Ternary hydride shows signs of room-temperature superconductivity at high pressures appeared first on Physics World.

International research collaborations will be increasingly led by scientists in China over the coming decade. That is according to a new study by researchers at the University of Chicago, which finds that the power balance in international science has shifted markedly away from the US and towards China over the last 25 years (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 122 e2414893122).

To explore China’s role in global science, the team used a machine-learning model to predict the lead researchers of almost six million scientific papers that involved international collaboration listed by online bibliographic catalogue OpenAlex. The model was trained on author data from 80 000 papers published in high-profile journals that routinely detail author contributions, including team leadership.

The study found that between 2010 and 2012 there were only 4429 scientists from China who were likely to have led China-US collaborations. By 2023, this number had risen to 12714, meaning that the proportion of team leaders affiliated with Chinese institutions had risen from 30% to 45%.

If this trend continues, China will hit “leadership parity” with the US in chemistry, materials science and computer science by 2028, with maths, physics and engineering being level by 2031. The analysis also suggests that China will achieve leadership parity with the US in eight “critical technology” areas by 2030, including AI, semiconductors, communications, energy and high-performance computing.

For China-UK partnerships, the model found that equality had already been reached in 2019, while EU and China leadership roles will be on par this year or next. The authors also found that China has been actively training scientists in nations in the “Belt and Road Initiative” which seeks to connect China closer to the world through investments and infrastructure projects.

This, the researchers warn, limits the ability to isolate science done in China. Instead, they suggest that it could inspire a different course of action, with the US and other countries expanding their engagement with the developing world to train a global workforce and accelerate scientific advancements beneficial to their economies.

The post Scientific collaborations increasingly more likely to be led by Chinese scientists, finds study appeared first on Physics World.

This episode explores the scientific and technological significance of 2D materials such as graphene. My guest is Antonio Rossi, who is a researcher in 2D materials engineering at the Italian Institute of Technology in Genoa.

Rossi explains why 2D materials are fundamentally different than their 3D counterparts – and how these differences are driving scientific progress and the development of new and exciting technologies.

Graphene is the most famous 2D material and Rossi talks about today’s real-world applications of graphene in coatings. We also chat about the challenges facing scientists and engineers who are trying to exploit graphene’s unique electronic properties.

Rossi’s current research focuses on two other promising 2D materials – tungsten disulphide and hexagonal boron nitride. He explains why tungsten disulphide shows great technological promise because of its favourable electronic and optical properties; and why hexagonal boron nitride is emerging as an ideal substrate for creating 2D devices.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming an important tool in developing new 2D materials. Rossi explains how his team is developing feedback loops that connect AI with the fabrication and characterization of new materials. Our conversation also touches on the use of 2D materials in quantum science and technology.

IOP Publishing’s new Progress In Series: Research Highlights website offers quick, accessible summaries of top papers from leading journals like Reports on Progress in Physics and Progress in Energy. Whether you’re short on time or just want the essentials, these highlights help you expand your knowledge of leading topics.

The post Unlocking the potential of 2D materials: graphene and much more appeared first on Physics World.

Microcirculation – the flow of blood through the smallest vessels – is responsible for distributing oxygen and nutrients to tissues and organs throughout the body. Mapping this flow at the whole-organ scale could enhance our understanding of the circulatory system and improve diagnosis of vascular disorders. With this aim, researchers at the Institute Physics for Medicine Paris (Inserm, ESPCI-PSL, CNRS) have combined 3D ultrasound localization microscopy (ULM) with a multi-lens array method to image blood flow dynamics in entire organs with micrometric resolution, reporting their findings in Nature Communications.

“Beyond understanding how an organ functions across different spatial scales, imaging the vasculature of an entire organ reveals the spatial relationships between macro- and micro-vascular networks, providing a comprehensive assessment of its structural and functional organization,” explains senior author Clement Papadacci.

The 3D ULM technique works by localizing intravenously injected microbubbles. Offering a spatial resolution roughly ten times finer than conventional ultrasound, 3D ULM can map and quantify micro-scale vascular structures. But while the method has proved valuable for mapping whole organs in small animals, visualizing entire organs in large animals or humans is hindered by the limitations of existing technology.

To enable wide field-of-view coverage while maintaining high-resolution imaging, the team – led by PhD student Nabil Haidour under Papadacci’s supervision – developed a multi-lens array probe. The probe comprises an array of 252 large (4.5 mm²) ultrasound transducer elements. The use of large elements increases the probe’s sensitive area to a total footprint of 104 x 82 mm, while maintaining a relatively low element count.

Each transducer element is equipped with an individual acoustic diverging lens. “Large elements alone are too directive to create an image, as they cannot generate sufficient overlap or interference between beams,” Papadacci explains. “The acoustic lenses reduce this directivity, allowing the elements to focus and coherently combine signals in reception, thus enabling volumetric image formation.”

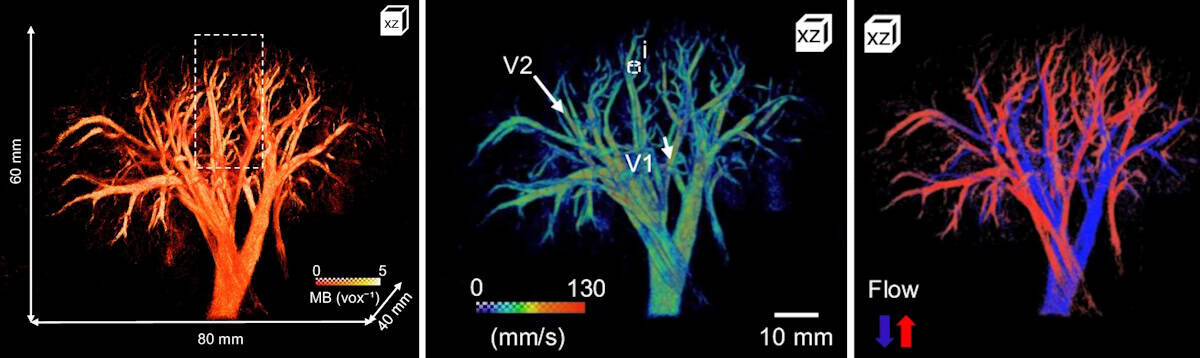

After validating their method via numerical simulations and phantom experiments, the team used a multi-lens array probe driven by a clinical ultrasound system to perform 3D dynamic ULM of an entire explanted porcine heart – considered an ideal cardiac model as its vascular anatomies and dimensions are comparable to those of humans.

The heart was perfused with microbubble solution, enabling the probe to visualize the whole coronary microcirculation network over a large volume of 120 x 100 x 82 mm, with a spatial resolution of around 125 µm. The technique enabled visualization of both large vessels and the finest microcirculation in real time. The team also used a skeletonization algorithm to measure vessel radii at each voxel, which ranged from approximately 75 to 600 µm.

As well as structural imaging, the probe can also assess flow dynamics across all vascular scales, with a high temporal resolution of 312 frames/s. By tracking the microbubbles, the researchers estimated absolute flow velocities ranging from 10 mm/s in small vessels to over 300 mm/s in the largest. They could also differentiate arteries and veins based on the flow direction in the coronary network.

Next, the researchers used the multi-lens array probe to image the entire kidney and liver of an anaesthetized pig at the Veterinary school of Maison Alfort, with the probe positioned in front of the kidney or liver, respectively, and held using an articulated arm. They employed electrocardiography to synchronize the ultrasound acquisitions with periods of minimal respiratory motion and injected microbubble solution intravenously into the animal’s ear.

The probe mapped the vascular network of the kidney over a 60 x 80 x 40 mm volume with a spatial resolution of 147 µm. The maximum 3D absolute flow velocity was approximately 280 mm/s in the large vessels and the vessel radii ranged from 70 to 400 µm. The team also used directional flow measurements to identify the arterial and venous flow systems.

Liver imaging is more challenging due to respiratory, cardiac and stomach motions. Nevertheless, 3D dynamic ULM enabled high-depth visualization of a large volume of liver vasculature (65 x 100 x 82 mm) with a spatial resolution of 200 µm. Here, the researchers used dynamic velocity measurement to identify the liver’s three blood networks (arterial, venous and portal veins).

“The combination of whole-organ volumetric imaging with high-resolution vascular quantification effectively addresses key limitations of existing modalities, such as ultrasound Doppler imaging, CT angiography and 4D flow MRI,” they write.

Clinical applications of 3D dynamic ULM still need to be demonstrated, but Papadacci suggests that the technique has strong potential for evaluating kidney transplants, coronary microcirculation disorders, stroke, aneurysms and neoangiogenesis in cancer. “It could also become a powerful tool for monitoring treatment response and vascular remodelling over time,” he adds.

Papadacci and colleagues anticipate that translation to human applications will be possible in the near future and plan to begin a clinical trial early in 2026.

The post Ultrasound probe maps real-time blood flow across entire organs appeared first on Physics World.

La suite de la fameuse bande dessinée Lore Olympus vient tout juste de sortir. En effet, le tome 9 est disponible depuis hier ! Pour rappel, c’est Rachel Smythe qui en est à l’origine.

Le monde souterrain a une reine !

Perséphone et Hadès sont enfin réunis lorsque la déesse du printemps, bannie, retourne aux Enfers pour revendiquer sa place de reine. Maintenant qu’Hadès et Perséphone ont vaincu et emprisonné à nouveau Cronos, assoiffé de pouvoir, plus rien ne peut les séparer, et les années d’éloignement n’ont fait qu’accroître leur désir l’un pour l’autre. Mais les autres Olympiens ne peuvent s’empêcher de s’en mêler, poussant le couple à officialiser les choses par un couronnement – et un mariage.

Ignorant ceux qui tentent de définir leur relation, Hadès et Perséphone s’efforcent de vivre à leur propre rythme et de se concentrer sur la reconstruction des Enfers. Ils commencent par enquêter sur la façon dont Cronos a pu s’échapper et apprennent l’horrible vérité : il a capturé un jeune dieu puissant dont les capacités lui permettent de projeter ses pensées en dehors du Tartare – des pensées qu’il utilise pour tourmenter Héra. Bien que la forme physique de Cronos soit enfermée, l’Olympe ne sera jamais libre tant qu’ils n’auront pas sauvé le jeune dieu de son emprise.

Ce tome 9 est disponible depuis hier en librairie pour le tarif habituel, soit 24,95 €.

Sortie Hugo BD – Lore Olympus tome 9 a lire sur Vonguru.

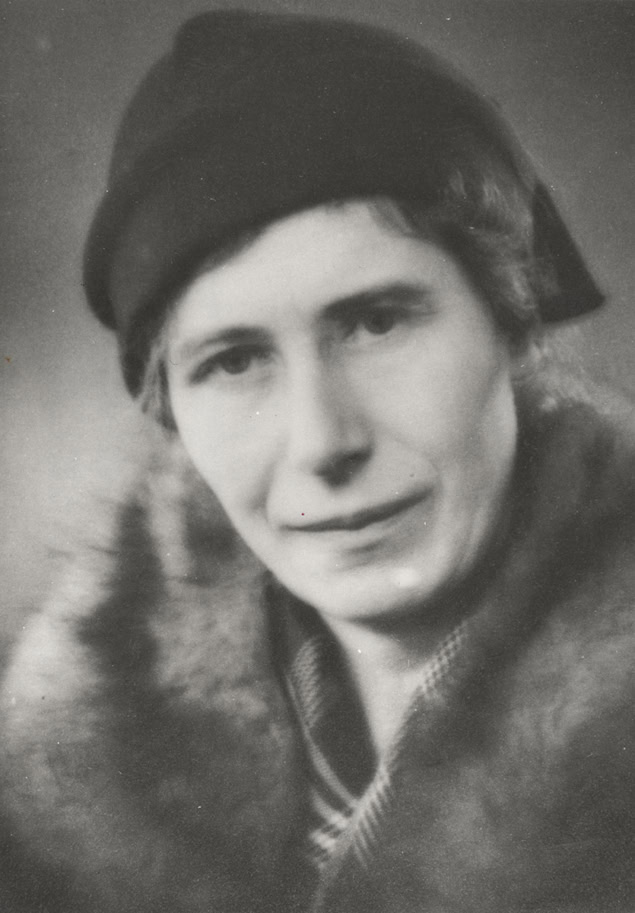

In the 1930s a little-known Danish seismologist calculated that the Earth has a solid inner core, within the liquid outer core identified just a decade earlier. The international scientific community welcomed Inge Lehmann as a member of the relatively new field of geophysics – yet in her home country, Lehmann was never really acknowledged as more than a very competent keeper of instruments.

It was only after retiring from her seismologist job aged 65 that Lehmann was able to devote herself full time to research. For the next 30 years, Lehmann worked and published prolifically, finally receiving awards and plaudits that were well deserved. However, this remarkable scientist, who died in 1993 aged 104, rarely appears in short histories of her field.

In a step to address this, we now have a biography of Lehmann: If I Am Right, and I Know I Am by Hanne Strager, a Danish biologist, science museum director and science writer. Strager pieces together Lehmann’s life in great detail, as well as providing potted histories of the scientific areas that Lehmann contributed to.

A brief glance at the chronology of Lehmann’s education and career would suggest that she was a late starter. She was 32 when she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from the University of Copenhagen, 40 when she received her master’s degree in geodosy and was appointed state geodesist for Denmark. Lehmann faced a litany of struggles in her younger years, from health problems and money issues to the restrictions placed on most women’s education in the first decades of the 20th century.

The limits did not come from her family. Lehmann and her sister were sent to good schools, she was encouraged to attend university, and was never pressed to get married, which would likely have meant the end of her education. When she asked her father’s permission to go to the University of Cambridge, his objection was the cost – though the money was found and Lehmann duly went to Newnham College in 1910. While there she passed all the preliminary exams to study for Cambridge’s legendarily tough mathematical tripos but then her health forced her to leave.

Lehmann was suffering from stomach pains; she had trouble sleeping; her hair was falling out. And this was not her first breakdown. She had previously studied for a year at the University of Copenhagen before then, too, dropping out and moving to the countryside to recover her health.

The cause of Lehmann’s recurrent breakdowns is unknown. They unfortunately fed into the prevailing view of the time that women were too fragile for the rigours of higher learning. Strager attempts to unpick these historical attitudes from Lehmann’s very real medical issues. She posits that Lehmann had severe anxiety or a physical limitation to how hard she could push herself. But this conclusion fails to address the hostile conditions Lehmann was working in.

In Cambridge Lehmann formed firm friendships that lasted the rest of her life. But women there did not have the same access to learning as men. They were barred from most libraries and laboratories; could not attend all the lectures; were often mocked and belittled by professors and male students. They could sit exams but, even if they passed, would not be awarded a degree. This was a contributing factor when after the First World War Lehmann decided to complete her undergraduate studies in Copenhagen rather than Cambridge.

Lehmann is described as quiet, shy, reticent. But she could be eloquent in writing and once her career began she established connections with scientists all over the world by writing to them frequently. She was also not the wallflower she initially appeared to be. When she was hired as an assistant at Denmark’s Institute for the Measurement of Degrees, she quickly complained that she was being using as an office clerk, not a scientist, and she would not have accepted the job had she known this was the role. She was instead given geometry tasks that she found intellectually stimulating, which led her to seismology.

Unfortunately, soon after this Lehmann’s career development stalled. While her title of “state geodesist” sounds impressive, she was the only seismologist in Denmark for decades, responsible for all the seismographs in Denmark and Greenland. Her days were filled with the practicalities of instrument maintenance and publishing reports of all the data collected.

Despite repeated requests Lehmann didn’t receive an assistant, which meant she never got round to completing a PhD, though she did work towards one in her evenings and weekends. Time and again opportunities for career advancement went to men who had the title of doctor but far less real experience in geophysics. Even after she co-founded the Danish Geophysical Society in 1934, her native country overlooked her.

The breakthrough that should have changed this attitude from the men around her came in 1936, when she published “P’ ”. This innocuous sounding paper was revolutionary, but based firmly in the P wave and S wave measurements that Lehmann routinely monitored.

In If I Am Right, and I Know I Am, Strager clearly explains what P and S waves are. She also highlights why they were being studied by both state seismologist Lehmann and Cambridge statistician Harold Jeffreys, and how they led to both scientists’ biggest breakthroughs.

After any seismological disturbance, P and S waves propagate through the Earth. P waves move at different speeds according to the material they encounter, while S waves cannot pass through liquid or air. This knowledge allowed Lehmann to calculate whether any fluctuations in seismograph readings were earthquakes, and if so where the epicentre was located. And it led to Jeffreys’ insight that the Earth must have a liquid core.

Lehmann’s attention to detail meant she spotted a “discontinuity” in P waves that did not quite match a purely liquid core. She immediately wrote to Jeffreys that she believed there was another layer to the Earth, a solid inner core, but he was dismissive – which led to her writing the statement that forms the title of this book. Undeterred, she published her discovery in the journal of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics.

In 1951 Lehmann visited the institution that would become her second home: the Lamont Geological Observatory in New York state. Its director Maurice Ewing invited her to work there on a sabbatical, arranging all the practicalities of travel and housing on her behalf.

Here, Lehmann finally had something she had lacked her entire career: friendly collaboration with colleagues who not only took her seriously but also revered her. Lehmann took retirement from her job in Denmark and began to spend months of every year at the Lamont Observatory until well into her 80s.

Though Strager tells us this “second phase” of Lehmann’s career was prolific, she provides little detail about the work Lehmann did. She initially focused on detecting nuclear tests during the Cold War. But her later work was more varied, and continued after she lost most of her vision. Lehmann published her final paper aged 99.

If I Am Right, and I Know I Am is bookended with accounts of Strager’s research into one particular letter sent to Lehmann, an anonymous (because the final page has been lost) declaration of love. It’s an insight into the lengths Strager went to – reading all the surviving correspondence to and from Lehmann; interviewing living relatives and colleagues; working with historians both professional and amateur; visiting archives in several countries.

But for me it hit the wrong tone. The preface and epilogue are mostly speculation about Lehmann’s love life. Lehmann destroyed a lot of her personal correspondence towards the end of her life, and chose what papers to donate to an archive. To me those are the actions of a woman who wants to control the narrative of her life – and does not want her romances to be written about. I would have preferred instead another chapter about her later work, of which we know she was proud.

But for the majority of its pages, this is a book of which Strager can be proud. I came away from it with great admiration for Lehmann and an appreciation for how lonely life was for many women scientists even in recent history.

The post Inge Lehmann: the ground-breaking seismologist who faced a rocky road to success appeared first on Physics World.

The LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA collaboration has detected strong evidence for second-generation black holes, which were formed from earlier mergers of smaller black holes. The two gravitational wave signals provide one of the strongest confirmations to date for how Einstein’s general theory of relativity describes rotating black holes. Studying such objects also provides a testbed for probing new physics beyond the Standard Model.

Over the past decade, the global network of interferometers operated by LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA have detected close to 300 gravitational waves (GWs) – mostly from the mergers of binary black holes.

In October 2024 the network detected a clear signal that pointed back to a merger that occurred 700 million light-years away. The progenitor black holes were 20 and 6 solar masses and the larger object was spinning at 370 Hz, which makes it one of the fastest-spinning black holes ever observed.

Just one month later, the collaboration detected the coalescence of another highly imbalanced binary (17 and 8 solar masses), 2.4 billion light-years away. This signal was even more unusual – showing for the first time that the larger companion was spinning in the opposite direction of the binary orbit.

While conventional wisdom says black holes should not be spinning at such high rates, the observations were not entirely unexpected. “With both events having one black hole, which is both significantly more massive than the other and rapidly spinning, [the observations] provide tantalizing evidence that these black holes were formed from previous black hole mergers,” explains Stephen Fairhurst at Cardiff University, spokesperson of the LIGO Collaboration. If this were the case, the two GW signals – called GW241011 and GW241110 – are first observations of second-generation black holes. This is because when a binary merges, the resulting second-generation object tends to have a large spin.

The GW241011 signal was particularly clear, which allowed the team to make the third-ever observation of higher harmonic modes. These are overtones in the GW signal that become far clearer when the masses of the coalescing bodies are highly imbalanced.

The precision of the GW241011 measurement provides one of the most stringent verifications so far of general relativity. The observations also support Roy Kerr’s prediction that rapid rotation distorts the shape of a black hole.

“We now know that black holes are shaped like Einstein and Kerr predicted, and general relativity can add two more checkmarks in its list of many successes,” says team member Carl-Johan Haster at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “This discovery also means that we’re more sensitive than ever to any new physics that might lie beyond Einstein’s theory.”

This new physics could include hypothetical particles called ultralight bosons. These could form in clouds just outside the event horizons of spinning black holes, and would gradually drain a black hole’s rotational energy via a quantum effect called superradiance.

The idea is that the observed second-generation black holes had been spinning for billions of years before their mergers occurred. This means that if ultralight bosons were present, they cannot have removed lots of angular momentum from the black holes. This places the tightest constraint to date on the mass of ultralight bosons.

“Planned upgrades to the LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA detectors will enable further observations of similar systems,” Fairhurst says. “They will enable us to better understand both the fundamental physics governing these black hole binaries and the astrophysical mechanisms that lead to their formation.”

Haster adds, “Each new detection provides important insights about the universe, reminding us that each observed merger is both an astrophysical discovery but also an invaluable laboratory for probing the fundamental laws of physics”.

The observations are described in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The post Rapidly spinning black holes put new limit on ultralight bosons appeared first on Physics World.

Quantum error correction codes protect quantum information from decoherence and quantum noise, and are therefore crucial to the development of quantum computing and the creation of more reliable and complex quantum algorithms. One example is the five-qubit error correction code, five being the minimum number of qubits required to fix single-qubit errors. These contain five physical qubits (a basic off/on unit of quantum information made using trapped ions, superconducting circuits, or quantum dots) to correct one logical qubit (a collection of physical qubits arranged in such a way as to correct errors). Yet imperfections in the hardware can still lead to quantum errors.

A method of testing quantum error correction codes is self-testing. Self-testing is a powerful tool for verifying quantum properties using only input-output statistics, treating quantum devices as black boxes. It has evolved from bipartite systems consisting of two quantum subsystems, to multipartite entanglement, where entanglement is among three or more subsystems, and now to genuinely entangled subspaces, where every state is fully entangled across all subsystems. Genuinely entangled subspaces offer stronger, guaranteed entanglement than general multipartite states, making them more reliable for quantum computing and error correction.

In this research, self-testing techniques are used to certify genuinely entangled logical subspaces within the five-qubit code on photonic and superconducting platforms. This is achieved by preparing informationally complete logical states that span the entire logical space, meaning the set is rich enough to fully characterize the behaviour of the system. They deliberately introduce basic quantum errors by simulating Pauli errors on the physical qubit, which mimics real-world noise. Finally, they use mathematical tests known as Bell inequalities, adapted to the framework used in quantum error correction, to check whether the system evolves in the initial logical subspaces after the errors are introduced.

Extractability measures tell you how close the tested quantum system is to the ideal target state, with 1 being a perfect match. The certification is supported by extractability measures of at least 0.828 ± 0.006 and 0.621 ± 0.007 for the photonic and superconducting systems, respectively. The photonic platform achieved a high extractability score, meaning the logical subspace was very close to the ideal one. The superconducting platform had a lower score but still showed meaningful entanglement. These scores show that the self-testing method works in practice and confirm strong entanglement in the five-qubit code on both platforms.

This research contributes to the advancement of quantum technologies by providing robust methods for verifying and characterizing complex quantum structures, which is essential for the development of reliable and scalable quantum systems. It also demonstrates that device-independent certification can extend beyond quantum states and measurements to more general quantum structures.

Certification of genuinely entangled subspaces of the five qubit code via robust self-testing

Yu Guo et al 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 050501

Quantum error correction for beginners by Simon J Devitt, William J Munro and Kae Nemoto (2013)

The post Making quantum computers more reliable appeared first on Physics World.

For almost a century, physicists have tried to understand why and how materials become magnetic. From refrigerator magnets to magnetic memories, the microscopic origins of magnetism remain a surprisingly subtle puzzle — especially in materials where electrons behave both like individual particles and like a collective sea.

In most transition-metal compounds, magnetism comes from the dance between localized and mobile electrons. Some electrons stay near their home atoms and form tiny magnetic moments (spins), while others roam freely through the crystal. The interaction between these two types of electrons produces “double-exchange” ferromagnetism — the mechanism that gives rise to the rich magnetic behaviour of materials such as manganites, famous for their colossal magnetoresistance (a dramatic change in electrical resistance under a magnetic field). Traditionally, scientists modelled this behaviour by treating the localized spins as classical arrows — big and well-defined, like compass needles. This approximation works well enough for explaining basic ferromagnetism, but experiments over the last few decades have revealed strange features that defy the classical picture. In particular, neutron scattering studies of manganites showed that the collective spin excitations, called magnons, do not behave as expected. Their energy spectrum “softens” (the waves slow down) and their sharp signals blur into fuzzy continua — a sign that the magnons are losing their coherence. Until now, these effects were usually blamed on vibrations of the atomic lattice (phonons) or on complex interactions between charge, spin, and orbital motion.

A new theoretical study challenges that assumption. By going fully quantum mechanical — treating every localized spin not as a classical arrow but as a true quantum object that can fluctuate, entangle, and superpose — the researchers have reproduced these puzzling experimental observations without invoking phonons at all. Using two powerful model systems (a quantum version of the Kondo lattice and a two-orbital Hubbard model), the team simulated how electrons and spins interact when no semiclassical approximations are allowed. The results reveal a subtle quantum landscape. Instead of a single type of electron excitation, the system hosts two. One behaves like a spinless fermion — a charge carrier stripped of its magnetic identity. The other forms a broad, “incoherent” band of excitations arising from local quantum triplets. These incoherent states sit close to the Fermi level and act as a noisy background — a Stoner-like continuum — that the magnons can scatter off. The result: magnons lose their coherence and energy in just the way experiments observe.

Perhaps most surprisingly, this mechanism doesn’t rely on the crystal lattice at all. It’s an intrinsic consequence of the quantum nature of the spins themselves. Larger localized spins, such as those in classical manganites, tend to suppress the effect — explaining why decoherence is weaker in some materials than others. Consequently, the implications reach beyond manganites. Similar quantum interplay may occur in iron-based superconductors, ruthenates, and heavy-fermion systems where magnetism and superconductivity coexist. Even in materials without permanent local moments, strong electronic correlations can generate the same kind of quantum magnetism.

In short, this work uncovers a purely electronic route to complex magnetic dynamics — showing that the quantum personality of the electron alone can mimic effects once thought to require lattice distortions. By uniting electronic structure and spin excitations under a single, fully quantum description, it moves us one step closer to understanding how magnetism truly works in the most intricate materials.

Magnon damping and mode softening in quantum double-exchange ferromagnets

A Moreo et al 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 068001

Nanoscale electrodynamics of strongly correlated quantum materials by Mengkun Liu, Aaron J Sternbach and D N Basov (2017)

The post Quantum ferromagnets without the usual tricks: a new look at magnetic excitations appeared first on Physics World.

Mise à jour 04/01 — 699 €, c’est le nouveau prix plancher du MacBook Air M2. Il était déjà disponible à ce prix chez Boulanger en milieu de semaine. C’est au tour de Darty de le proposer à ce prix en collaboration avec Rakuten. Pour bénéficier de cette offre, il suffit de saisir le code RAKUTEN50 lors de la commande. La transaction est gérée par Rakuten, mais la livraison est l’œuvre de Darty.

Cette configuration embarque 16 Go de RAM et 256 Go d’espace de stockage. Une offre à ne pas rater, si vous cherchez un Mac à petit prix.

Mise à jour 26/12 — Boulanger poursuit sa double remise sur le MacBook Air M2 minuit qui le fait tomber à seulement 724 €, son prix le plus bas. La machine est affichée à 749 €, mais une fois dans le panier, une remise supplémentaire de 25 € est appliquée.

Lancé en 2022, le MacBook Air M2 est très agréable à utiliser : il est léger, silencieux, performant et endurant. Deux générations lui ont succédé, mais la formule n’a pas changé, si bien qu’il reste tout à fait dans le coup aujourd’hui. Les 16 Go de RAM sont suffisants pour les usages classiques. Les 256 Go de stockage peuvent, eux, être trop faibles pour certains, mais on peut pallier le problème avec un SSD externe.

Test du MacBook Air M2 : le saut dans l'air moderne

Mise à jour 20/12 — Petit à petit, le MacBook Air M2 se rapproche de la barre psychologique des 700 €. Ces derniers jours, on voit fleurir de plus en plus d’offres éphémères entre 720 et 750 €. Aujourd’hui, la meilleure nous vient du duo Rakuten / Darty : en saisissant le code DARTY10, vous pouvez obtenir le portable d’Apple à 739 €. Il s’agit d’une configuration avec 16 Go de RAM et 256 Go de SSD. La transaction est effectuée via Rakuten, mais la livraison est assurée par Darty. Amazon de son côté propose la même configuration pour 749 €.

Mise à jour 16/12 — Amazon riposte à son tour à Boulanger et propose le même MacBook Air M2 16 Go à 725 € !

Mise à jour 15/12 — En 2026, le prix des Mac pourrait à nouveau augmenter, mais 2026, c’est encore (un peu) loin. Autant dire qu’on ne reverra peut-être pas de si tôt un MacBook Air à 724 € ! À ce prix, vous pouvez obtenir chez Boulanger le MacBook Air M2 équipé de 16 Go et 256 de mémoire vive. Il s’agit bien entendu d’un modèle neuf ! Pour l’obtenir à ce prix, pensez à saisir le code NOEL25.

Mise à jour 11/12 — Le MacBook Air M2 est proposé ce jour à 749 € chez Boulanger ! Il s’agit du même modèle : 16 Go de RAM et 256 Go de SSD.

Mise à jour 09/12 — Depuis le Black Friday, les prix ont tendance à repartir à la hausse sur certaines configurations de Mac. Il reste toutefois de bonnes affaires à saisir ! Après avoir été proposé pendant quelques jours à 799 €, le MacBook Air M2 avec 16 Go de RAM et 256 Go de stockage est de nouveau affiché à 775 €. Mais la vraie surprise vient de Cdiscount, qui ne s’est pas contenté de s’aligner : le site dégaine une contre-offensive encore plus agressive. Avec le code MBA25, le même MacBook Air M2 tombe à 750 €, tout simplement l’un des meilleurs prix jamais vus pour ce modèle.

Le MacBook Air M4, lui, est proposé à 942,11 €. Il était resté longtemps à 899 €.

Mise à jour 3/12 — Amazon vient de baisser à nouveau le prix du MacBook Air M2 16 Go. Il est proposé au prix de 748 € !

Mise à jour 26/11 — Chaque jour, le MacBook Air M2 abandonne quelques euros. Le voilà disponible pour 773 € sur Amazon ! Pour l’avoir à ce prix, il vous faut activer le coupon qui est proposé !

Mise à jour 21/11 — Le prix du MacBook Air M2 repart à la baisse sur Amazon. Il est affiché ce jour à 798 €, mais Amazon lui retranche 15 € au moment de passer la commande. Ce qui nous ramène le MacBook Air M2 à 783 € !

Mise à jour le 14 novembre 14:10 : Le prix du MacBook Air M2 continue de dégringoler : on peut l’obtenir pour 773 € en ce moment chez Cdiscount. Il faudra pour cela entrer le code POMME25 à l’étape du paiement. Il s’agit de la version 256 Go et avec 16 Go de RAM. La machine est vendue et expédiée par Cdiscount. Ne traînez pas trop, car rien n’indique jusqu’à quand l’offre restera en ligne.

Article original : Si Apple a diminué récemment le prix du MacBook Air M4 13 pouces, qui est passé à 1 099 €, il n'y a pas encore de Mac portable réellement low cost dans la gamme… du moins pas chez Apple directement. En effet, de nombreux revendeurs proposent encore le MacBook Air M2 à la vente, dans sa variante dotée de 16 Go de RAM et de 256 Go de stockage. Et Amazon propose même une (petite) réduction : il est à 798 €, son prix le plus bas chez Amazon1.

La machine a été lancée en 2022 à 1 500 € (avec 8 Go de RAM), et c'est un ordinateur portable toujours performant, très autonome et silencieux, contrairement aux MacBook Pro M5, par exemple. Le MacBook Air M4 a évidemment un système sur puce plus moderne et plus performant, mais la puce M2 ne démérite pas. C'est la version noire (Minuit) qui est proposée à ce prix, et elle n'a qu'un défaut : elle est (très) sensible aux traces de doigts. Mais pour le reste, le MacBook Air M2 reste un excellent appareil, surtout à ce prix.

Soyons honnêtes : il est depuis quelques semaines à 799 €, mais ça reste une bonne affaire souvent méconnue. ↩︎

Using a new type of low-power, compact, fluid-based prism to steer the beam in a laser scanning microscope could transform brain imaging and help researchers learn more about neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The “electrowetting prism” utilized was developed by a team led by Juliet Gopinath from the electrical, computer and energy engineering and physics departments at the University of Colorado at Boulder (CU Boulder) and Victor Bright from CU Boulder’s mechanical engineering department, as part of their ongoing collaboration on electrically controllable optical elements for improving microscopy techniques.

“We quickly became interested in biological imaging, and work with a neuroscience group at University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus that uses mouse models to study neuroscience,” Gopinath tells Physics World. “Neuroscience is not well understood, as illustrated by the neurodegenerative diseases that don’t have good cures. So a great benefit of this technology is the potential to study, detect and treat neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and schizophrenia,” she explains.

The researchers fabricated their patented electrowetting prism using custom deposition and lithography methods. The device consists of two immiscible liquids housed in a 5 mm tall, 4 mm diameter glass tube, with a dielectric layer on the inner wall coating four independent electrodes. When an electric field is produced by applying a potential difference between a pair of electrodes on opposite sides of the tube, it changes the surface tension and therefore the curvature of the meniscus between the two liquids. Light passing through the device is refracted by a different amount depending on the angle of tilt of the meniscus (as well as on the optical properties of the liquids chosen), enabling beams to be steered by changing the voltage on the electrodes.

Beam steering for scanning in imaging and microscopy can be achieved via several means, including mechanically controlled mirrors, glass prisms or acousto-optic deflectors (in which a sound wave is used to diffract the light beam). But, unlike the new electrowetting prisms, these methods consume too much power and are not small or lightweight enough to be used for miniature microscopy of neural activity in the brains of living animals.

In tests detailed in Optics Express, the researchers integrated their electrowetting prism into an existing two-photon laser scanning microscope and successfully imaged individual 5 µm-diameter fluorescent polystyrene beads, as well as large clusters of those beads.

They also used computer simulation to study how the liquid–liquid interface moved, and found that when a sinusoidal voltage is used for actuation, at 25 and 75 Hz, standing wave resonance modes occur at the meniscus – a result closely matched by a subsequent experiment that showed resonances at 24 and 72 Hz. These resonance modes are important for enhancing device performance since they increase the angle through which the meniscus can tilt and thus enable optical beams to be steered through a greater range of angles, which helps minimize distortions when raster scanning in two dimensions.

Bright explains that this research built on previous work in which an electrowetting prism was used in a benchtop microscope to image a mouse brain. He cites seeing the individual neurons as a standout moment that, coupled with the current results, shows their prism is now “proven and ready to go”.

Gopinath and Bright caution that “more work is needed to allow human brain scans, such as limiting voltage requirements, allowing the device to operate at safe voltage levels, and miniaturization of the device to allow faster scan speeds and acquiring images at a much faster rate”. But they add that miniaturization would also make the device useful for endoscopy, robotics, chip-scale atomic clocks and space-based communication between satellites.

The team has already begun investigating two other potential applications: LiDAR (light detection and ranging) systems and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Next, the researchers “hope to integrate the device into a miniaturized microscope to allow imaging of the brain in freely moving animals in natural outside environments,” they say. “We also aim to improve the packaging of our devices so they can be integrated into many other imaging systems.”

The post Fluid-based laser scanning technique could improve brain imaging appeared first on Physics World.

To coincide with a week of quantum-related activities organized by the Institute of Physics (IOP) in the UK, Physics World has just published a free-to-read digital magazine to bring you up to date about all the latest developments in the quantum world.

The 62-page Physics World Quantum Briefing 2.0 celebrates the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ) and also looks ahead to a quantum-enhanced future.

Marking 100 years since the advent of quantum mechanics, IYQ aims to raise awareness of the impact of quantum physics and its myriad future applications, with a global diary of quantum-themed public talks, scientific conferences, industry events and more.

The 2025 Physics World Quantum Briefing 2.0, which follows on from the first edition published in May, contains yet more quantum topics for you to explore and is once again divided into “history”, “mystery” and “industry”.

You can find out more about the contributions of Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose to quantum science; explore weird phenomena such as causal order and quantum superposition; and discover the latest applications of quantum computing.

A century after quantum mechanics was first formulated, many physicists are still undecided on some of the most basic foundational questions. There’s no agreement on which interpretation of quantum mechanics holds strong; whether the wavefunction is merely a mathematical tool or a true representation of reality; or what impact an observer has on a quantum state.

Some of the biggest unanswered questions in physics – such as finding the quantum/classical boundary or reconciling gravity and quantum mechanics – lie at the heart of these conundrums. So as we look to the future of quantum – from its fundamentals to its technological applications – let us hope that some answers to these puzzles will become apparent as we crack the quantum code to our universe.

This article forms part of Physics World‘s contribution to the 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ), which aims to raise global awareness of quantum physics and its applications.

Stayed tuned to Physics World and our international partners throughout the year for more coverage of the IYQ.

Find out more on our quantum channel.

The post Intrigued by quantum? Explore the 2025 <em>Physics World Quantum Briefing 2.0</em> appeared first on Physics World.

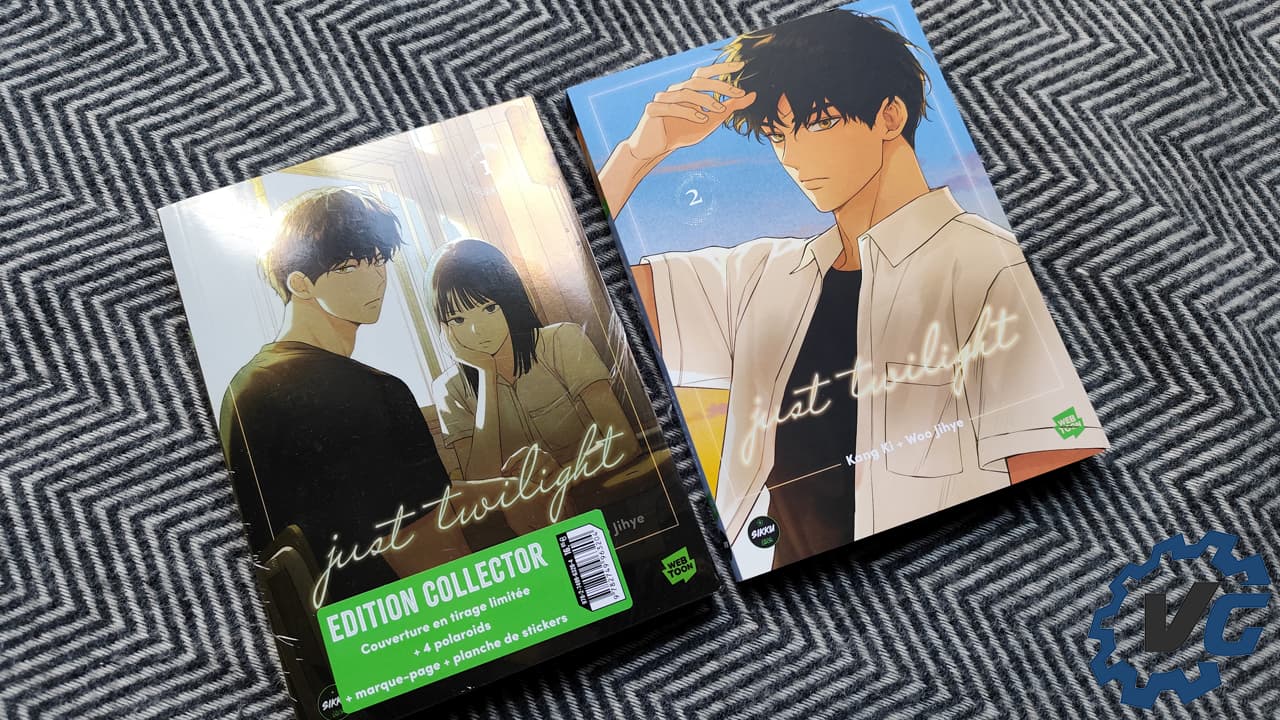

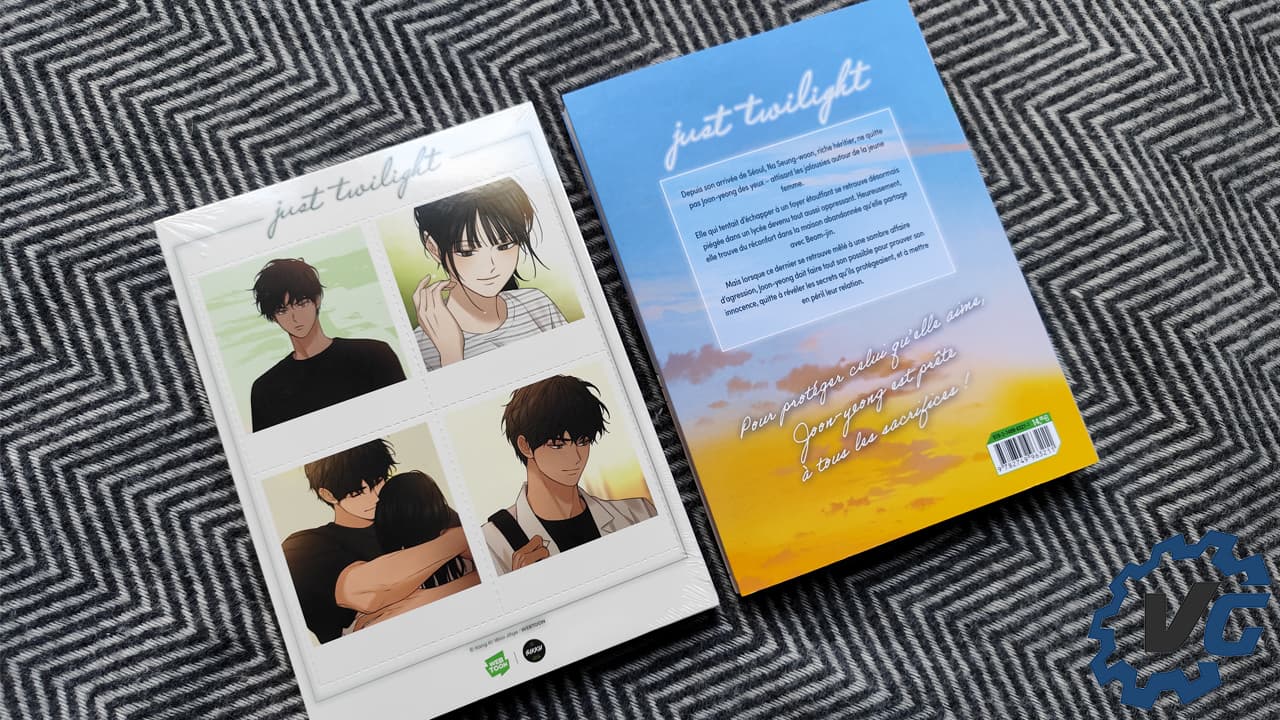

Les éditions Michel Lafon nous dévoilent un tout nouveau webtoon en ce mois d’octobre : Just Twilight de Kang Ki et Woo Jihye. En plus, l’éditeur nous ravie avec la sortie des deux premiers tomes simultanément.

Pour le tome 1 collector : une couverture métallisée exclusive, contenant 4 ex-libris format polaroïds, une planche de stickers et un marque-page !

Joon-yeong, meilleure élève de son lycée, cherche désespérément un refuge pour étudier, loin du domicile familial qu’elle fuit. Par hasard, elle découvre une maison abandonnée dans la forêt, idéale pour travailler en paix. Mais le lieu est déjà occupé : Beom-jin, son camarade de classe à mauvaise réputation, s’y cache lui aussi. Une étrange cohabitation se met alors en place entre ces deux lycéens que tout oppose, unis par l’envie de préserver ce havre secret. Et dans ce lieu hors du monde, quelque chose d’inattendu pourrait bien naître.

Les tomes 1 et 2 sont sortis simultanément le 16 octobre dernier. Le premier tome est disponible au tarif de 16,95 € tandis que vous trouverez tome 2 pour 14,95 €.

Sortie Michel Lafon – Just Twilight Tomes 1 et 2 a lire sur Vonguru.

Unless you’ve been living under a stone, you can’t have failed to notice that 2025 marks the first 100 years of quantum mechanics. A massive milestone, to say the least, about which much has been written in Physics World and elsewhere in what is the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ). However, I’d like to focus on a specific piece of quantum technology, namely quantum computing.

I keep hearing about quantum computers, so people must be using them to do cool things, and surely they will soon be as commonplace as classical computers. But as a physicist-turned-engineer working in the aerospace sector, I struggle to get a clear picture of where things are really at. If I ask friends and colleagues when they expect to see quantum computers routinely used in everyday life, I get answers ranging from “in the next two years” to “maybe in my lifetime” or even “never”.

Before we go any further, it’s worth reminding ourselves that quantum computing relies on several key quantum properties, including superposition, which gives rise to the quantum bit, or qubit. The basic building block of a quantum computer – the qubit – exists as a combination of 0 and 1 states at the same time and is represented by a probabilistic wave function. Classical computers, in contrast, use binary digital bits that are either 0 or 1.

Also vital for quantum computers is the notion of entanglement, which is when two or more qubits are co-ordinated, allowing them to share their quantum information. In a highly correlated system, a quantum computer can explore many paths simultaneously. This “massive scale” parallel processing is how quantum may solve certain problems exponentially faster than a classical computer.

The other key phenomenon for quantum computers is quantum interference. The wave-like nature of qubits means that when different probability amplitudes are in phase, they combine constructively to increase the likelihood of the right solution. Conversely, destructive interference occurs when amplitudes are out of phase, making it less likely to get the wrong answer.

Quantum interference is important in quantum computing because it allows quantum algorithms to amplify the probability of correct answers and suppress incorrect ones, making calculations much faster. Along with superposition and entanglement, it means that quantum computers could process and store vast numbers of probabilities at once, outstripping even the best classical supercomputers.

To me, it all sounds exciting, but what have quantum computers ever done for us so far? It’s clear that quantum computers are not ready to be deployed in the real world. Significant technological challenges need to be overcome before they become fully realisable. In any case, no-one is expecting quantum computers to displace classical computers “like for like”: they’ll both be used for different things.

Yet it seems that the very essence of quantum computing is also its Achilles heel. Superposition, entanglement and interference – the quantum properties that will make it so powerful – are also incredibly difficult to create and maintain. Qubits are also extremely sensitive to their surroundings. They easily lose their quantum state due to interactions with the environment, whether via stray particles, electromagnetic fields, or thermal fluctuations. Known as decoherence, it makes quantum computers prone to error.

That’s why quantum computers need specialized – and often cryogenically controlled – environments to maintain the quantum states necessary for accurate computation. Building a quantum system with lots of interconnected qubits is therefore a major, expensive engineering challenge, with complex hardware and extreme operating conditions. Developing “fault-tolerant” quantum hardware and robust error-correction techniques will be essential if we want reliable quantum computation.

As for the development of software and algorithms for quantum systems, there’s a long way to go, with a lack of mature tools and frameworks. Quantum algorithms require fundamentally different programming paradigms to those used for classical computers. Put simply, that’s why building reliable, real-world deployable quantum computers remains a grand challenge.

Despite the huge amount of work that still lies in store, quantum computers have already demonstrated some amazing potential. The US firm D-Wave, for example, claimed earlier this year to have carried out simulations of quantum magnetic phase transitions that wouldn’t be possible with the most powerful classical devices. If true, this was the first time a quantum computer had achieved “quantum advantage” for a practical physics problem (whether the problem was worth solving is another question).

There is also a lot of research and development going on around the world into solving the qubit stability problem. At some stage, there will likely be a breakthrough design for robust and reliable quantum computer architecture. There is probably a lot of technical advancement happening right now behind closed doors.

The first real-world applications of quantum computers will be akin to the giant classical supercomputers of the past. If you were around in the 1980s, you’ll remember Cray supercomputers: huge, inaccessible beasts owned by large corporations, government agencies and academic institutions to enable vast amounts of calculations to be performed (provided you had the money).

And, if I believe what I read, quantum computers will not replace classical computers, at least not initially, but work alongside them, as each has its own relative strengths. Quantum computers will be suited for specific and highly demanding computational tasks, such as drug discovery, materials science, financial modelling, complex optimization problems and increasingly large artificial intelligence and machine-learning models.

These are all things beyond the limits of classical computer resource. Classical computers will remain relevant for everyday tasks like web browsing, word processing and managing databases, and they will be essential for handling the data preparation, visualization and error correction required by quantum systems.

And there is one final point to mention, which is cyber security. Quantum computing poses a major threat to existing encryption methods, with potential to undermine widely used public-key cryptography. There are concerns that hackers nowadays are storing their stolen data in anticipation of future quantum decryption.

Having looked into the topic, I can now see why the timeline for quantum computing is so fuzzy and why I got so many different answers when I asked people when the technology would be mainstream. Quite simply, I still can’t predict how or when the tech stack will pan out. But as IYQ draws to a close, the future for quantum computers is bright.

The post Quantum computing: hype or hope? appeared first on Physics World.

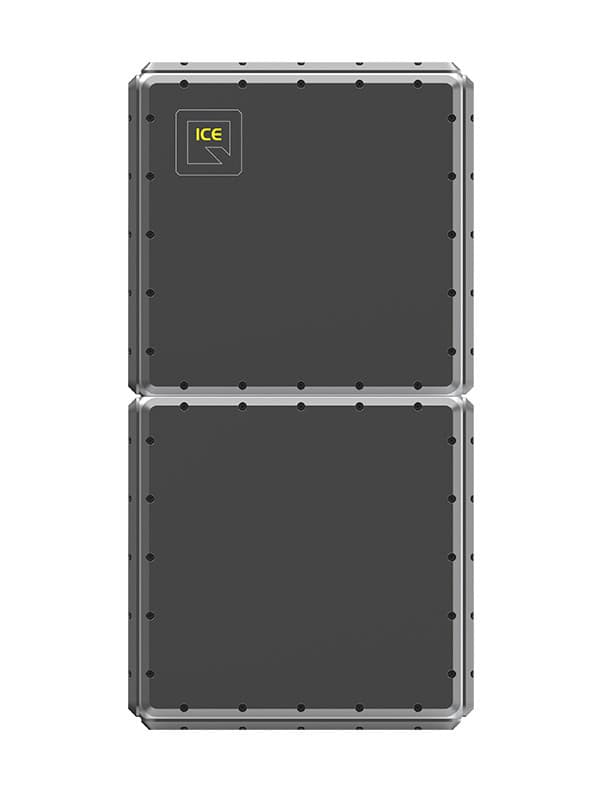

At the centre of most quantum labs is a large cylindrical cryostat that keeps the delicate quantum hardware at ultralow temperatures. These cryogenic chambers have expanded to accommodate larger and more complex quantum systems, but the scientists and engineers at UK-based cryogenics specialist ICEoxford have taken a radical new approach to the challenge of scalability. They have split the traditional cryostat into a series of cube-shaped modules that slot into a standard 19-inch rack mount, creating an adaptable platform that can easily be deployed alongside conventional computing infrastructure.

“We wanted to create a robust, modular and scalable solution that enables different quantum technologies to be integrated into the cryostat,” says Greg Graf, the company’s engineering manager. “This approach offers much more flexibility, because it allows different modules to be used for different applications, while the system also delivers the efficiency and reliability that are needed for operational use.”

The standard configuration of the ICE-Q platform has three separate modules: a cryogenics unit that provides the cooling power, a large payload for housing the quantum chip or experiment, and a patent-pending wiring module that attaches to the side of the payload to provide the connections to the outside world. Up to four of these side-loading wiring modules can be bolted onto the payload at the same time, providing thousands of external connections while still fitting into a standard rack. For applications where space is not such an issue, the payload can be further extended to accommodate larger quantum assemblies and potentially tens of thousands of radio-frequency or fibre-optic connections.

The cube-shaped form factor provides much improved access to these external connections, whether for designing and configuring the system or for ongoing maintenance work. The outer shell of each module consists of panels that are easily removed, offering a simple mechanism for bolting modules together or stacking them on top of each other to provide a fully scalable solution that grows with the qubit count.

The flexible design also offers a more practical solution for servicing or upgrading an installed system, since individual modules can be simply swapped over as and when needed. “For quantum computers running in an operational environment it is really important to minimize the downtime,” says Emma Yeatman, senior design engineer at ICEoxford. “With this design we can easily remove one of the modules for servicing, and replace it with another one to keep the system running for longer. For critical infrastructure devices, it is possible to have built-in redundancy that ensures uninterrupted operation in the event of a failure.”

Other features have been integrated into the platform to make it simple to operate, including a new software system for controlling and monitoring the ultracold environment. “Most of our cryostats have been designed for researchers who really want to get involved and adapt the system to meet their needs,” adds Yeatman. “This platform offers more options for people who want an out-of-the-box solution and who don’t want to get hands on with the cryogenics.”

Such a bold design choice was enabled in part by a collaborative research project with Canadian company Photonic Inc, funded jointly by the UK and Canada, that was focused on developing an efficient and reliable cryogenics platform for practical quantum computing. That R&D funding helped to reduce the risk of developing an entirely new technology platform that addresses many of the challenges that ICEoxford and its customers had experienced with traditional cryostats. “Quantum technologies typically need a lot of wiring, and access had become a real issue,” says Yeatman. “We knew there was an opportunity to do better.”

However, converting a large cylindrical cryostat into a slimline and modular form factor demanded some clever engineering solutions. Perhaps the most obvious was creating a frame that allows the modules to be bolted together while still remaining leak tight. Traditional cryostats are welded together to ensure a leak-proof seal, but for greater flexibility the ICEoxford team developed an assembly technique based on mechanical bonding.

The side-loading wiring module also presented a design challenge. To squeeze more wires into the available space, the team developed a high-density connector for the coaxial cables to plug into. An additional cold-head was also integrated into the module to pre-cool the cables, reducing the overall heat load generated by such large numbers of connections entering the ultracold environment.

Meanwhile, the speed of the cooldown and the efficiency of operation have been optimized by designing a new type of heat exchanger that is fabricated using a 3D printing process. “When warm gas is returned into the system, a certain amount of cooling power is needed just to compress and liquefy that gas,” explains Kelly. “We designed the heat exchangers to exploit the returning cold gas much more efficiently, which enables us to pre-cool the warm gas and use less energy for the liquefaction.”

The initial prototype has been designed to operate at 1 K, which is ideal for the photonics-based quantum systems being developed by ICEoxford’s research partner. But the modular nature of the platform allows it to be adapted to diverse applications, with a second project now underway with the Rutherford Appleton Lab to develop a module that that will be used at the forefront of the global hunt for dark matter.

Already on the development roadmap are modules that can sustain temperatures as low as 10 mK – which is typically needed for superconducting quantum computing – and a 4 K option for trapped-ion systems. “We already have products for each of those applications, but our aim was to create a modular platform that can be extended and developed to address the changing needs of quantum developers,” says Kelly.

As these different options come onstream, the ICEoxford team believes that it will become easier and quicker to deliver high-performance cryogenic systems that are tailored to the needs of each customer. “It normally takes between six and twelve months to build a complex cryogenics system,” says Graf. “With this modular design we will be able to keep some of the components on the shelf, which would allow us to reduce the lead time by several months.”

More generally, the modular and scalable platform could be a game-changer for commercial organizations that want to exploit quantum computing in their day-to-day operations, as well as for researchers who are pushing the boundaries of cryogenics design with increasingly demanding specifications. “This system introduces new avenues for hardware development that were previously constrained by the existing cryogenics infrastructure,” says Kelly. “The ICE-Q platform directly addresses the need for colder base temperatures, larger sample spaces, higher cooling powers, and increased connectivity, and ensures our clients can continue their aggressive scaling efforts without being bottlenecked by their cooling environment.”

The post Modular cryogenics platform adapts to new era of practical quantum computing appeared first on Physics World.

Due to government shutdown restrictions currently in place in the US, the researchers who headed up this study have not been able to comment on their work

Laser plasma acceleration (LPA) may be used to generate multi-gigaelectronvolt muon beams, according to physicists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) in the US. Their work might help in the development of ultracompact muon sources for applications such as muon tomography – which images the interior of large objects that are inaccessible to X-ray radiography.

Muons are charged subatomic particles that are produced in large quantities when cosmic rays collide with atoms 15–20 km high up in the atmosphere. Muons have the same properties as electrons but are around 200 times heavier. This means they can travel much further through solid structures than electrons. This property is exploited in muon tomography, which analyses how muons penetrate objects and then exploits this information to produce 3D images.

The technique is similar to X-ray tomography used in medical imaging, with the cosmic-ray radiation taking the place of artificially generated X-rays and muon trackers the place of X-ray detectors. Indeed, depending on their energy, muons can traverse metres of rock or other materials, making them ideal for imaging thick and large structures. As a result, the technique has been used to peer inside nuclear reactors, pyramids and volcanoes.

As many as 10,000 muons from cosmic rays reach each square metre of the Earth’s surface every minute. These naturally produced particles have unpredictable properties, however, and they also only come from the vertical direction. This fixed directionality means that can take months to accumulate enough data for tomography.

Another option is to use the large numbers of low-energy muons that can be produced in proton accelerator facilities by smashing a proton beam onto a fixed carbon target. However, these accelerators are large and expensive facilities, limiting their use in muon tomography.

Physicists led by Davide Terzani have now developed a new compact muon source based on LPA-generated electron beams. Such a source, if optimized, could be deployed in the field and could even produce muon beams in specific directions.

In LPA, an ultra-intense, ultra-short, and tightly focused laser pulse propagates into an “under-dense” gas. The pulse’s extremely high electric field ionizes the gas atoms, freeing the electrons from the nuclei, so generating a plasma. The ponderomotive force, or radiation pressure, of the intense laser pulse displaces these electrons and creates an electrostatic wave that produces accelerating fields orders of magnitude higher than what is possible in the traditional radio-frequency cavities used in conventional accelerators.

LPAs have all the advantages of an ultra-compact electron accelerator that allows for muon production in a small-size facility such as BeLLA, where Terzani and his colleagues work. Indeed, in their experiment, they succeeded in generating a 10 GeV electron beam in a 30 cm gas target for the first time.

The researchers collided this beam with a dense target, such as tungsten. This slows the beam down so that it emits Bremsstrahlung, or braking radiation, which interacts with the material, producing secondary products that include lepton–antilepton pairs, such as electron–positron and muon–antimuon pairs. Behind the converter target, there is also a short-lived burst of muons that propagates roughly along the same axis as the incoming electron beam. A thick concrete shielding then filters most of the secondary products, letting the majority of muons pass through it.

Crucially, Terzani and colleagues were able to separate the muon signal from the large background radiation – something that can be difficult to do because of the inherent inefficiency of the muon production process. This allowed them to identify two different muon populations coming from the accelerator. These were a collimated, forward directed population, generated by pair production; and a low-energy, isotropic, population generated by meson decay.

Muons can ne used in a range of fields, from imaging to fundamental particle physics. As mentioned, muons from cosmic rays are currently used to inspect large and thick objects not accessible to regular X-ray radiography – a recent example of this is the discovery of a hidden chamber in Khufu’s Pyramid. They can also be used to image the core of a burning blast furnace or nuclear waste storage facilities.

While the new LPA-based technique cannot yet produce muon fluxes suitable for particle physics experiments – to replace a muon injector, for example – it could offer the accelerator community a convenient way to test and develop essential elements towards making a future muon collider.

The experiment in this study, which is detailed in Physical Review Accelerators and Beams, focused on detecting the passage of muons, unequivocally proving their signature. The researchers conclude that they now have a much better understanding of the source of these muons.

Unfortunately, the original programme that funded this research has ended, so future studies are limited at the moment. Not to be disheartened, the researchers say they strongly believe in the potential of LPA-generated muons and are working on resuming some of their experiments. For example, they aim to measure the flux and the spectrum of the resulting muon beam using completely different detection techniques based on ultra-fast particle trackers, for example.

The LBNL team also wants to explore different applications, such as imaging deep ore deposits – something that will be quite challenging because it poses strict limitations on the minimum muon energy required to penetrate soil. Therefore, they are looking into how to increase the muon energy of their source.

The post Portable source could produce high-energy muon beams appeared first on Physics World.