Nothing Projector Black Series 120" motorisé: l'écran géant pour projecteur UST

VR puzzle adventure Tin Hearts will bring its first act to Quest in February.

Developed by Rogue Sun and IPHIGAMES, Tin Hearts is a Lemmings-style game that explores the story of a fictional Victorian inventor, Albert Butterworth. Guiding toy soldiers through this Dickensian world with block-based puzzles, VR support arrived in a post-launch update on PS VR2 and Steam last year. Originally targeting a December 11 launch, that's now been delayed to February 12, 2026.

Detailed in a press release, publisher Wired Productions calls Act 1 a standalone episode where these tiny soldiers are appropriately dressed for the festive season in an attic filled with toys. Costing $5.99 for the first part, the publisher previously stated Acts 2, 3, and 4 will follow “in the coming weeks” on Quest. No specific release dates have been confirmed yet.

Originally released through a now delisted PC VR prologue on PC VR in 2018, we had positive impressions in our Tin Hearts VR preview two years ago. Stating it offers “some well-considered mechanics” that caught our attention, we believed it provides “enjoyable puzzles and an intriguing whimsical setting.”

Tin Hearts is out now in full on flatscreen platforms, PS VR2, and PC VR. Act 1 arrives on the Meta Quest platform on February 12, 2026.

This article was originally published on November 14, 2025. It was updated on December 10, 2025, after Wired Productions confirmed Act 1's release date on Quest has been delayed.

As we enter the final stretch of the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ), I hope you’ve enjoyed our extensive quantum coverage over the last 12 months. We’ve tackled the history of the subject, explored some of the unexplained mysteries that still make quantum physics so exciting, and examined many of the commercial applications of quantum technology. You can find most of our coverage collected into two free-to-read digital Quantum Briefings, available here and here on the Physics World website.

Over the last 100 years since Werner Heisenberg first developed quantum mechanics on the island of Helgoland in June 1925, quantum mechanics has proved to be an incredibly powerful, successful and logically consistent theory. Our understanding of the subatomic world is no longer the “lamentable hodgepodge of hypotheses, principles, theorems and computational recipes”, as the Israeli physicist and philosopher Max Jammer memorably once described it.

In fact, quantum mechanics has not just transformed our understanding of the natural world; it has immense practical ramifications too, with so-called “quantum 1.0” technologies – lasers, semiconductors and electronics – underpinning our modern world. But as was clear from the UK National Quantum Technologies Showcase in London last week, organized by Innovate UK, the “quantum 2.0” revolution is now in full swing.

The day-long event, which is now in its 10th year, featured over 100 exhibitors, including many companies that are already using fundamental quantum concepts such as entanglement and superposition to support the burgeoning fields of quantum computing, quantum sensing and quantum communication. The show was attended by more than 3000 delegates, some of whom almost had to be ushered out of the door at closing time, so keen were they to keep talking.

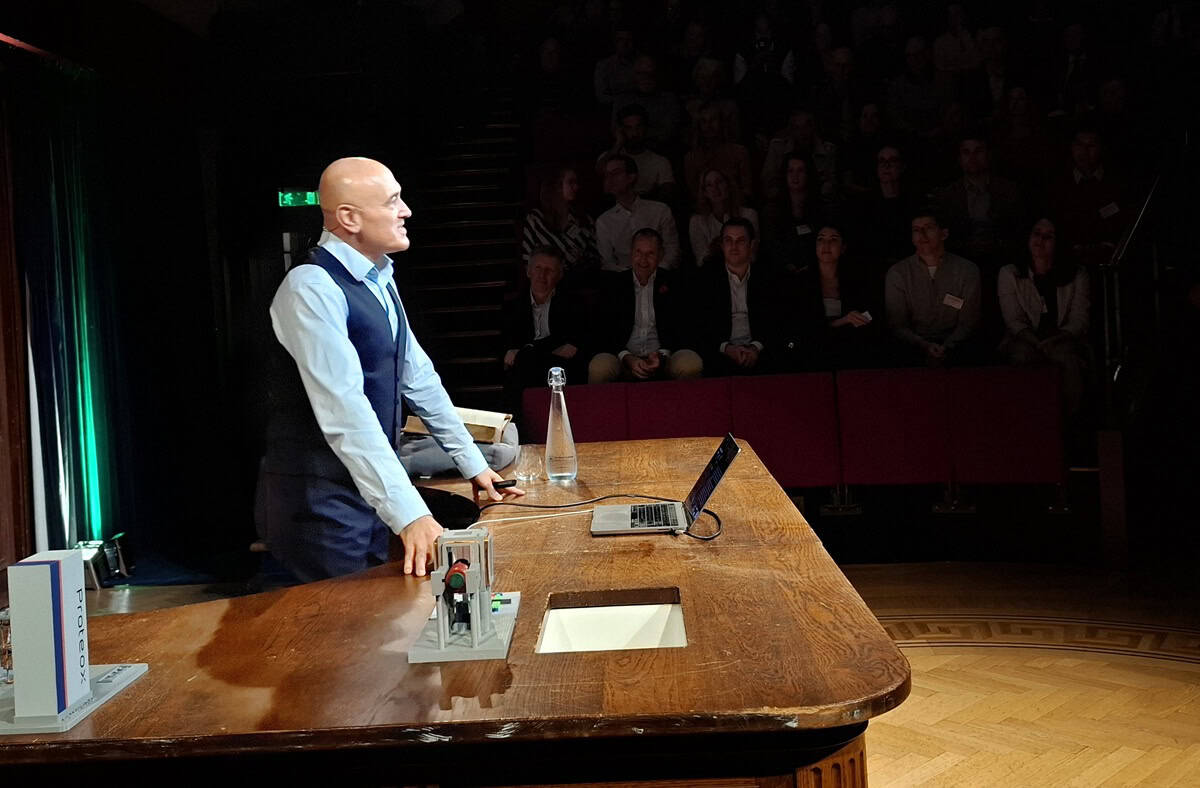

Last week also saw a two-day conference at the historic Royal Institution (RI) in central London that was a centrepiece of IYQ in the UK and Ireland. Entitled Quantum Science and Technology: the First 100 Years; Our Quantum Future and attended by over 300 people, it was organized by the History of Physics and the Business Innovation and Growth groups of the Institute of Physics (IOP), which publishes Physics World.

The first day, focusing on the foundations of quantum mechanics, ended with a panel discussion – chaired by my colleague Tushna Commissariat and Daisy Shearer from the UK’s National Quantum Computing Centre – with physicists Fay Dowker (Imperial College), Jim Al-Khalili (University of Surrey) and Peter Knight. They talked about whether the quantum wavefunction provides a complete description of physical reality, prompting much discussion with the audience. As Al-Khalili wryly noted, if entanglement has emerged as the fundamental feature of quantum reality, then “decoherence is her annoying and ever-present little brother”.

Knight, meanwhile, who is a powerful figure in quantum-policy circles, went as far as to say that the limit of decoherence – and indeed the boundary between the classical and quantum worlds – is not a fixed and yet-to-be revealed point. Instead, he mused, it will be determined by how much money and ingenuity and time physicists have at their disposal.

On the second day of the IOP conference at the RI, I chaired a discussion that brought together four future leaders of the subject: Mehul Malik (Heriot-Watt University) and Sarah Malik (University College London) along with industry insiders Nicole Gillett (Riverlane) and Muhammad Hamza Waseem (Quantinuum).

As well as outlining the technical challenges in their fields, the speakers all stressed the importance of developing a “skills pipeline” so that the quantum sector has enough talented people to meet its needs. Also vital will be the need to communicate the mysteries and potential of quantum technology – not just to the public but to industrialists, government officials and venture capitalists. By many measures, the UK is at the forefront of quantum tech – and it is a lead it should not let slip.

The week ended with Al-Khalili giving a public lecture, also at the Royal Institution, entitled “A new quantum world: ‘spooky’ physics to tech revolution”. It formed part of the RI’s famous Friday night “discourses”, which this year celebrate their 200th anniversary. Al-Khalili, who also presents A Life Scientific on BBC Radio 4, is now the only person ever to have given three RI discourses.

After the lecture, which was sold out, he took part in a panel discussion with Knight and Elizabeth Cunningham, a former vice-president for membership at the IOP. Al-Khalili was later presented with a special bottle of “Glentanglement” whisky made by Glasgow-based Fraunhofer UK for the Scottish Quantum Technology cluster.

The post The future of quantum physics and technology debated at the Royal Institution appeared first on Physics World.

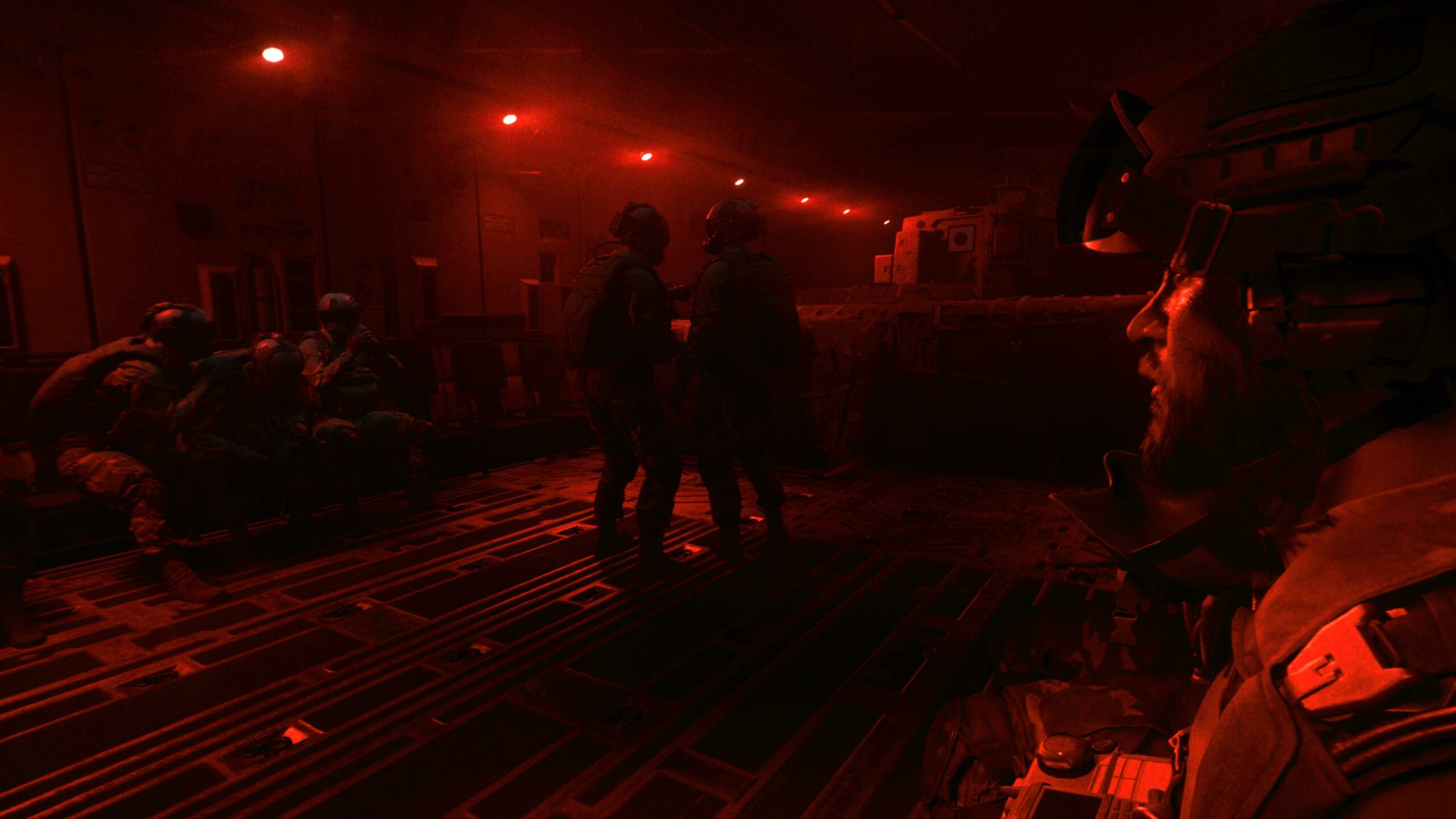

Battlefield c’est un jeu vidéo qu’on ne présente plus et qui fait la part belle aux confrontations online sur le champs de bataille… Mais c’est aussi une campagne solo mouvementée qu’on retrouve dans ce nouvel épisode Battlefield 6… Attardons-nous dessus…

Découpée en 9 chapitres qui sont autant de missions variées, cette campagne solo est un peu courte, comme souvent (6h environ…), mais elle est rythmée et vaut le coup de s’y consacrer avant de se lancer dans le multi.

Sans être attachée à un scénario spécialement ficelé, l’histoire nous fait voyager à travers le globe (Egypte, New York, Europe…) en incarnant différents personnages d’une unité d’élite américaine en guerre contre une milice privée…

On voit donc du pays mais aussi des ambiances différentes, de nuit ou de jour avec différentes approches dans le gameplay entre infiltration et assaut. Comme dans le multi, on évolue à pied ou à bord de véhicules avec des spécialités spécifiques comme sniper ou autre… Ainsi, l’approche est toujours différente même si les ennemis, eux, sont souvent un peu teubés malheureusement…

La campagne offre souvent des maps assez ouvertes mais toujours dirigistes. On suit une progression finalement assez linéaire mais dans des lieux mouvementés pour une approche parfois cinématographique plutôt spectaculaire et très explosive…

Testé sur PS5, le jeu est graphiquement très solide avec des effets de lumières réalistes et une physique exemplaire en ce qui concerne notamment la destruction des bâtiments. C’est un gros point fort du titre dans son ensemble.

Bien sûr, BF6 prend tout son sens en multijoueurs online avec des maps et des modes spécifiques pour des confrontations bien plus tactiques et pleines de rebondissements. Cela dit, la campagne solo reste un indispensable à mon sens pour entrer dans l’univers avec une approche certes plus dirigiste mais aussi plus immersive, avec une ambiance particulière. Battelfield porte bien son nom et, alors que la concurrence pointe le bout de son nez aujourd’hui, reste une référence en la matière.

Cet article TEST de BATTLEFIELD 6 – A travers la campagne… est apparu en premier sur Insert Coin.

Phénomène des années 2000-2010, sur PC, consoles mais aussi et surtout sur mobiles ou consoles portables, Plants vs. Zombie revient cette année sur Nintendo Switch 2 avec une édition « Replanted », une sorte de remaster bienvenu tant le concept du jeu est drôle et addictif. Retour à la version 2D d’origine après des versions 3D qui restaient néanmoins intéressantes comme Garden Warfare, rappelez-vous.

Dès les premières notes de musique et les premières images, on se replonge avec nostalgie dans un jeu qui a eu beaucoup de succès auprès de tous types de joueuses et joueurs. Pour ceux qui ne connaitrait pas, on contrôle des plantes pour défendre un jardin d’invasions de zombies dans un jeu type Tower Defense. Les zombies arrivent par la droite et ne doivent pas arriver jusqu’à notre maison située à gauche.

On retrouve le mode aventure par lequel on débute pour passer différents niveaux successives qui nous permettent de glaner au fur et à mesure de nouvelles plantes. Les fameux pistou-pois sont toujours les plus efficaces avec des versions plus ou moins avancées comme ceux qui gèlent les zombies. On trouve aussi les cerises qui explosent tout aux alentours ou bien la plante carnivore qui grignotte le zombie qui approche ou bien les noix qui vont ralentir les assaillants, trop occupés à les dévorer…

Beaucoup d’armes écolos à notre actif donc pour en découdre au mieux face à des vagues ennemis de plus en plus redoutables. Evidemment, ils sont parfois plus nombreux mais eux aussi possèdent des variantes avec le lanceur de javelot, le footballeur américain et j’en passe… ils peuvent ainsi parfois être plus rapide ou plus difficile à tuer…

A nous, donc, de bien choisir nos plantes avant chaque vagues car on ne pourra pas tout utiliser à chaque fois. Il faut donc prendre garde aux armes gourmandes car, en effet, ces armes doivent se recharger avec les rayons du soleil, et pour gagner des rayons du soleil il faut planter des tournesols (ceux qui tombent du ciel ne suffiront pas et lors des vagues de nuit c’est forcément plus compliqué…). Là aussi, il faut don bien composer avec cet axe « gestion ».

On retrouve bien sûr Dave le Dingo, voisin farfelu qui va pouvoir nous vendre des petites choses afin de faire évoluer au mieux notre équipement.

Pour aller plus loin dans le fun, le jeu propose d’autres modes et notamment un mode 2 joueurs en local (coop ou versus) qui est plutôt sympa et bien conçu. Si le mode coop reste assez classique, il s’agit surtout d’être coordonné, le mode est versus est plus original pour celui qui gère les zombies. C’est en effet une première qui permet de faire avancer ces amusants morts-vivants un peu à la manière des plantes avec ici, une recharge en cervelles et non en rayons du soleil…

Parlons également des mini-jeux proposés avec du bowling à base noix, le zombie manchot, ce genre de petits jeux efficaces qui se marient bien au concept. Mais on trouve aussi un mode Enigmes qui propose de petits défis un peu plus stratégiques avec une difficulté croissante. Une bonne idée en tous cas pour les plus acharnés.

Visuellement, le titre est très beau et très coloré sur la Switch 2 avec une animation fluide. Mais la direction artistique reste celle qu’on connait, et c’est sans doute pas plus mal.

Plants vs. Zombies : Replanted est un remake bienvenu d’un concept qui a toujours fait mouche. On gagne ici en contenu avec des modes de jeux amusants et efficace et notamment la possibilité d’en découdre à 2 dans un jeu plutôt solitaire à la base. La recette est toujours parfaite pour un jeu que les plus anciens redécouvriront avec nostalgie. Les plus jeunes découvriront un principe addictif et délirant qui leur plaira à coup sûr.

Cet article TEST de PLANTS VS ZOMBIES: REPLANTED – Les gens du jardin sont de retour!… est apparu en premier sur Insert Coin.

Significant progress towards answering one of the Clay Mathematics Institute’s seven Millennium Prize Problems has been achieved using deep learning. The challenge is to establish whether or not the Navier-Stokes equation of fluid dynamics develops singularities. The work was done by researchers in the US and UK – including some at Google Deepmind. Some team members had already shown that simplified versions of the equation could develop stable singularities, which reliably form. In the new work, the researchers found unstable singularities, which form only under very specific conditions.

The Navier–Stokes partial differential equation was developed in the early 19th century by Claude-Louis Navier and George Stokes. It has proved its worth for modelling incompressible fluids in scenarios including water flow in pipes; airflow around aeroplanes; blood moving in veins; and magnetohydrodynamics in plasmas.

No-one has yet proved, however, whether smooth, non-singular solutions to the equation always exist in three dimensions. “In the real world, there is no singularity…there is no energy going to infinity,” says fluid dynamics expert Pedram Hassanzadeh of the University of Chicago. “So if you have an equation that has a singularity, it tells you that there is some physics that is missing.” In 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute in Denver, Colorado listed this proof as one of seven key unsolved problems in mathematics, offering a reward of $1,000,000 for an answer.

Researchers have traditionally tackled the problem analytically, but in recent decades high-level computational simulations have been used to assist in the search. In a 2023 paper, mathematician Tristan Buckmaster of New York University and colleagues used a special type of machine learning algorithm called a physics-informed neural network to address the question.

“The main difference is…you represent [the solution] in a highly non-linear way in terms of a neural network,” explains Buckmaster. This allows it to occupy a lower-dimensional space with fewer free parameters, and therefore to be optimized more efficiently. Using this approach, the researchers successfully obtained the first stable singularity in the Euler equation. This is an analogy to the Navier-Stokes equation that does not include viscosity.

A stable singularity will still occur if the initial conditions of the fluid are changed slightly – although the time taken for them to form may be altered. An unstable singularity, however, may never occur if the initial conditions are perturbed even infinitesimally. Some researchers have hypothesized that any singularities in the Navier-Stokes equation must be unstable, but finding unstable singularities in a computer model is extraordinarily difficult.

“Before our result there hadn’t been an unstable singularity for an incompressible fluid equation found numerically,” says geophysicist Ching-Yao Lai of California’s Stanford University.

In the new work the authors of the original paper and others teamed up with researchers at Google Deepmind to search for unstable singularities in a bounded 3D version of the Euler equation using a physics-informed neural network. “Unlike conventional neural networks that learn from vast datasets, we trained our models to match equations that model the laws of physics,” writes Yongji Wang of New York University and Stanford on Deepmind’s blog. “The network’s output is constantly checked against what the physical equations expect, and it learns by minimizing its ‘residual’, the amount by which its solution fails to satisfy the equations.”

After an exhaustive search at a precision that is orders of magnitude higher than a normal deep learning protocol, the researchers discovered new families of singularities in the 3D Euler equation. They also found singularities in the related incompressible porous media equation used to model fluid flows in soil or rock; and in the Boussinesq equation that models atmospheric flows.

The researchers also gleaned insights into the strength of the singularities. This could be important as stronger singularities might be less readily smoothed out by viscosity when moving from the Euler equation to the Navier-Stokes equation. The researchers are now seeking to model more open systems to study the problem in a more realistic space.

Hassanzadeh, who was not involved in the work, believes that it is significant – although the results are not unexpected. “If the Euler equation tells you that ‘Hey, there is a singularity,’ it just tells you that there is physics that is missing and that physics becomes very important around that singularity,” he explains. “In the case of Euler we know that you get the singularity because, at the very smallest scales, the effects of viscosity become important…Finding a singularity in the Euler equation is a big achievement, but it doesn’t answer the big question of whether Navier-Stokes is a representation of the real world, because for us Navier-Stokes represents everything.”

He says the extension to studying the full Navier-Stokes equation will be challenging but that “they are working with the best AI people in the world at Deepmind,” and concludes “I’m sure it’s something they’re thinking about”.

The work is available on the arXiv pre-print server.

The post Neural networks discover unstable singularities in fluid systems appeared first on Physics World.

L’hiver approche, les soirées franchement froides aussi, et l’envie de s’envelopper dans quelque chose de doux et réconfortant se fait sentir. Duux, marque déjà connue pour ses appareils de confort domestique élégants, propose avec la Yentl sur-couverture chauffante Bubble Beige une expérience cocooning aussi esthétique qu’efficace. J’ai eu l’occasion de la tester ces derniers jours, et j’ai hâte de vous partager ses atouts (et défauts ?)

Vous retrouverez Yentl en 4 versions différentes, à rayure ou style bulle, en gris ou beige. Nous avons de notre côté opté pour les bulles grises pour aller au mieux avec notre intérieur, et côté dimensions, c’est du 200×200. À noter que les modèles rayés sur plus cher de 20 €. Le nôtre est quant à lui affiché au prix de 129,99 € directement sur le site de la marque.

Place au test !

Commençons notre test par notre partie unboxing où nous retrouverons à l’avant un visuel du plaid plié avec sa télécommande. Le nom de la marque ainsi que du modèle, Yentl et ses dimensions ainsi que sa fonction, « heated overblanket » soit en français sur-couverture chauffante sont bien représentés en compagnie de quelques fonctionnalités. Mais c’est à l’arrière que l’on retrouvera un descriptif plus complet avec notamment les spécifications et les fonctionnalités. Nous y reviendrons peu après plus en détails.

| Marque | Duux |

|---|---|

| Code EAN | 8716164983852 |

| Numéro de produit | DXOB11 |

| Couleur | Gris |

| Afficheur | Oui |

| Adapté aux enfants | Oui |

| Minuteur | 1 – 9 heures |

| Positions | 9 |

| Interrupteur marche/arrêt | Oui |

| Garantie | 24 mois |

| Inclus | Manuel |

| Spécifications techniques | |

| Consommation | 160W |

| Tension | 220 – 240 volts |

| Dimensions et poids | |

| Poids | 3,3 kg |

| Dimensions Emballage | 46 x 46 x 18 cm |

| Opération | Contrôleur avec LCD |

| Protection contre la surchauffe | Oui |

| Matériau | Fausse fourrure de première qualité |

| Lavable en machine | Oui, max. 30°C |

| Résistant au sèche-linge | Oui, uniquement sur la température la plus basse |

| Dimensions | 200 x 200 cm |

Dès le déballage, le ton est donné : la Yentl dégage une vraie impression de qualité. Son tissu façon fausse fourrure à effet « bubble » est incroyablement doux, moelleux, presque velouté sous les doigts. Le coloris gris s’intègre facilement à tout type de décoration intérieure, qu’on soit dans un salon moderne, une chambre bohème ou un van aménagé. Ce n’est pas seulement une couverture chauffante, c’est un vrai élément de confort visuel et tactile.

Avec ses 200 × 200 cm, elle est imposante, idéale pour deux personnes ou pour s’enrouler dedans seul. Sa taille généreuse lui permet de couvrir tout un lit, mais elle s’utilise tout aussi bien sur un canapé ou un fauteuil. Duux a pensé à la praticité : la commande est amovible, la couverture passe à la machine à 30 °C et même au sèche-linge, à basse température. Un détail qui change tout quand on a des enfants ou des animaux à la maison.

La puissance de 160 W suffit largement à chauffer la surface de manière homogène. En une dizaine de minutes, on sent déjà la chaleur se diffuser agréablement. Le contrôle propose neuf niveaux de chaleur, ce qui permet de vraiment ajuster selon la température de la pièce ou la sensibilité de chacun. La minuterie intégrée, réglable de une à neuf heures, est un vrai atout : on peut s’endormir tranquillement sans craindre que la couverture reste allumée toute la nuit. C’est d’ailleurs une fonction essentielle en matière de sécurité, tout comme la protection contre la surchauffe intégrée au système.

À l’usage, le confort est indéniable. On retrouve la sensation d’une chaleur douce et enveloppante, pas d’un chauffage artificiel. Le tissu reste respirant, on ne transpire pas dessous, et la chaleur se répartit bien sur l’ensemble du plaid. Que ce soit pour une soirée Netflix, une sieste, ou simplement un moment de détente après avoir couché les enfants, elle devient rapidement indispensable. Dans une région comme le Var, où les hivers ne sont pas extrêmes mais où les soirées peuvent vite devenir fraîches, elle permet d’éviter de raviver la cheminée. Mes enfants, surtout mon grand, l’adore ! Il s’y blottit dans le canapé les matins où il tombe du lit un peu trop tôt.

Côté design, Duux réussit presque un sans-faute. Contrairement à beaucoup de couvertures chauffantes qui font un peu accessoire médical, la Yentl a le look d’un plaid haut de gamme. Elle se fond dans le décor sans le moindre fil apparent. On la laisse volontiers sur le canapé, non pas parce qu’on ne sait pas où la ranger, mais parce qu’elle ajoute une touche cosy à la pièce.

Bien sûr, il faut garder à l’esprit que ce type de produit demande un minimum de précautions : ne pas la plier lorsqu’elle est en marche, vérifier l’état du câble et éviter de l’utiliser dans des contextes trop humides. Mais dans le cadre d’un usage domestique classique, le système semble bien fiable, et la qualité de fabrication inspire confiance.

C’est typiquement le genre d’objet qu’on adopte sans s’en rendre compte — et qu’on ne veut plus quitter une fois essayé. Cependant il y a deux bémols. Pour commencer, le câble est trop court selon la disposition de votre pièce et une rallonge s’impose pour une utilisation dans mon canapé, ce qui est tout de même gênant. Il n’y a pas de bonnes longueurs et je comprends le choix de Duux de ne pas avoir fait un câble de 3m de long. Cependant si comme moi, vous avez votre canapé en plein milieu de la pièce, cela peut être un souci. Dernier point, le plaid est de même assez lourd et ne se fait pas oublier lorsqu’il est sur nous.

En résumé, la Yentl Bubble grise de Duux réussit à combiner performance et raffinement. Elle chauffe vite, elle est douce, belle, et simple à entretenir. Elle n’est pas la moins chère du marché, mais son rapport qualité-prix reste très bon compte tenu de la finition et du confort qu’elle offre. Si vous cherchez une couverture chauffante à la fois élégante et efficace, capable d’accompagner vos soirées d’hiver ou vos escapades en van, la Yentl coche toutes les cases.

On rappellera que vous pourrez retrouvere Yentl en 4 versions différentes, à rayure ou style bulle, en gris ou beige. Nous avons de notre côté opté pour les bulles grises pour aller au mieux avec notre intérieur, et côté dimensions, c’est du 200×200. À noter que les modèles rayés sur plus cher de 20 €. Le nôtre est quant à lui affiché au prix de 129,99 € directement sur le site de la marque.

Test – Sur-couverture chauffante Yentl de Duux a lire sur Vonguru.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) looks set to lose a big proportion of its budget as a two-decade reorganization plan for the centre is being accelerated. The move, which is set to be complete by March, has left the Goddard campus with empty buildings and disillusioned employees. Some staff even fear that the actions during the 43-day US government shutdown, which ended on 12 November, could see the end of much of the centre’s activities.

Based in Greenbelt, Maryland, the GSFC has almost 10 000 scientists and engineers, about 7000 of whom are directly employed by NASA contractors. Responsible for many of NASA’s most important uncrewed missions, telescopes, and probes, the centre is currently working on the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2027, as well as the Dragonfly mission that is due to head for Saturn’s largest moon Titan in 2028.

The ability to meet those schedules has now been put in doubt by the Trump administration’s proposed budget for financial year 2026, which started in September. It calls for NASA to receive almost $19bn – far less than the $25bn it has received for the past two years. If passed, Goddard would lose more than 42% of its staff.

Congress, which passes the final budget, is not planning to cut NASA so deeply as it prepares its 2026 budget proposal. But on 24 September, Goddard managers began what they told employees was “a series of moves…that will reduce our footprint into fewer buildings”. The shift is intended to “bring down overall operating costs while maintaining the critical facilities we need for our core capabilities of the future”.

While this is part of a 20-year “master plan” for the GSFC that NASA’s leadership approved in 2019, the management’s memo stated that “all planned moves will take place over the next several months and be completed by March 2026″. A report in September by Democratic members of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, which is responsible for NASA, asserts that the cuts are “in clear violation of the [US] constitution [without] regard for the impacts on NASA’s science missions and workforce”.

On 3 November, the Goddard Engineers, Scientists and Technicians Association, a union representing NASA workers, reported that the GSFC had already closed over a third of its buildings, including some 100 labs. This had been done, it says, “with extreme haste and with no transparent strategy or benefit to NASA or the nation”. The union adds that the “closures are being justified as cost-saving but no details are being provided and any short-term savings are unlikely to offset a full account of moving costs and the reduced ability to complete NASA missions”.

Zoe Lofgren, the lead Democrat on the House of Representatives Science Committee, has demanded of Sean Duffy, NASA’s acting administrator, that the agency “must now halt” any laboratory, facility and building closure and relocation activities at Goddard. In a letter to Duffy dated 10 November, she also calls for the “relocation, disposal, excessing, or repurposing of any specialized equipment or mission-related activities, hardware and systems” to also end immediately.

Lofgren now wants NASA to carry out a “full accounting of the damage inflicted on Goddard thus far” by 18 November. Owing to the government shutdown, no GSFC or NASA official was available to respond to Physics World’s requests for a response.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has renominated billionaire entrepreneur Jared Isaacman as NASA’s administrator. Trump had originally nominated Isaacman, who had flown on a private SpaceX mission and carried out spacewalk, on the recommendation of SpaceX founder Elon Musk. But the administration withdrew the nomination in May following concerns among some Republicans that Isaacman had funded the Democrat party.

The post NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center hit by significant downsizing appeared first on Physics World.

Like any major endeavour, designing and fabricating semiconductor chips requires compromise. As well as trade-offs between cost and performance, designers also consider carbon emissions and other environmental impacts.

In this episode of the Physics World Weekly podcast, Margaret Harris reports from the Heidelberg Laureate Forum where she spoke to two researchers who are focused on some of these design challenges.

Up first is Mariam Elgamal, who’s doing a PhD at Harvard University on the development of environmentally sustainable computing systems. She explains why sustainability goes well beyond energy efficiency and must consider the manufacturing process and the chemicals used therein.

Harris also chats with Andrew Gunter, who is doing a PhD at the University of British Columbia on circuit design for computer chips. He talks about the maths-related problems that must be solved in order to translate a desired functionality into a chip that can be fabricated.

The post Designing better semiconductor chips: NP hard problems and forever chemicals appeared first on Physics World.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is used extensively within preclinical research, enabling molecular imaging of rodent brains, for example, to investigate neurodegenerative disease. Such imaging studies require the highest possible spatial resolution to resolve the tiny structures in the animal’s brain. A research team at the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST) in Japan has now developed the first PET scanner to achieve sub-0.5 mm spatial resolution.

Submillimetre-resolution PET has been demonstrated by several research groups. Indeed, the QST team previously built a PET scanner with 0.55 mm resolution – sufficient to visualize the thalamus and hypothalamus in the mouse brain. But identification of smaller structures such as the amygdala and cerebellar nuclei has remained a challenge.

“Sub-0.5 mm resolution is important to visualize mouse brain structures with high quantification accuracy,” explains first author Han Gyu Kang. “Moreover, this research work will change our perspective about the fundamental limit of PET resolution, which had been regarded to be around 0.5 mm due to the positron range of [the radioisotope] fluorine-18”.

With Monte Carlo simulations revealing that sub-0.5 mm resolution could be achievable with optimal detector parameters and system geometry, Kang and colleagues performed a series of modifications to their submillimetre-resolution PET (SR-PET) to create the new high-resolution PET (HR-PET) scanner.

The HR-PET, described in IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, is based around two 48 mm-diameter detector rings with an axial coverage of 23.4 mm. Each ring contains 16 depth-of-interaction (DOI) detectors (essential to minimize parallax error in a small ring diameter) made from three layers of LYSO crystal arrays stacked in a staggered configuration, with the outer layer coupled to a silicon photomultiplier (SiPM) array.

Compared with their previous design, the researchers reduced the detector ring diameter from 52.5 to 48 mm, which served to improve geometrical efficiency and minimize the noncollinearity effect. They also reduced the crystal pitch from 1.0 to 0.8 mm and the SiPM pitch from 3.2 to 2.4 mm, improving the spatial resolution and crystal decoding accuracy, respectively.

Other changes included optimizing the crystal thicknesses to 3, 3 and 5 mm for the first, second and third arrays, as well as use of a narrow energy window (440–560 keV) to reduce the scatter fraction and inter-crystal scattering events. “The optimized staggered three-layer crystal array design is also a key factor to enhance the spatial resolution by improving the spatial sampling accuracy and DOI resolution compared with the previous SR-PET,” Kang points out.

Performance tests showed that the HR-PET scanner had a system-level energy resolution of 18.6% and a coincidence timing resolution of 8.5 ns. Imaging a NEMA 22Na point source revealed a peak sensitivity at the axial centre of 0.65% for the 440–560 keV energy window and a radial resolution of 0.67±0.06 mm from the centre to 10 mm radial offset (using 2D filtered-back-projection reconstruction) – a 33% improvement over that achieved by the SR-PET.

To further evaluate the performance of the HR-PET, the researchers imaged a rod-based resolution phantom. Images reconstructed using a 3D ordered-subset-expectation-maximization (OSEM) algorithm clearly resolved all of the rods. This included the smallest rods with diameters of 0.5 and 0.45 mm, with average valley-to-peak ratios of 0.533 and 0.655, respectively – a 40% improvement over the SR-PET.

The researchers then used the HR-PET for in vivo mouse brain imaging. They injected 18F-FITM, a tracer used to image the central nervous system, into an awake mouse and performed a 30 min PET scan (with the animal anesthetized) 42 min after injection. For comparison, they scanned the same mouse for 30 min with a preclinical Inveon PET scanner.

After OSEM reconstruction, strong tracer uptake in the thalamus, hypothalamus, cerebellar cortex and cerebellar nuclei was clearly visible in the coronal HR-PET images. A zoomed image distinguished the cerebellar nuclei and flocculus, while sagittal and axial images visualized the cortex and striatum. Images from the Inveon, however, could barely resolve these brain structures.

The team also imaged the animal’s glucose metabolism using the tracer 18F-FDG. A 30 min HR-PET scan clearly delineated glucose transporter expression in the cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus and cerebellar nuclei. Here again, the Inveon could hardly identify these small structures.

The researchers note that the 18F-FITM and 18F-FDG PET images matched well with the anatomy seen in a preclinical CT scan. “To the best of our knowledge, this is the first separate identification of the hypothalamus, amygdala and cerebellar nuclei of mouse brain,” they write.

Future plans for the HR-PET scanner, says Kang, include using it for research on neurodegenerative disorders, with tracers that bind to amyloid beta or tau protein. “In addition, we plan to extend the axial coverage over 50 mm to explore the whole body of mice with sub-0.5 mm resolution, especially for oncological research,” he says. “Finally, we would like to achieve sub-0.3 mm PET resolution with more optimized PET detector and system designs.”

The post High-resolution PET scanner visualizes mouse brain structures with unprecedented detail appeared first on Physics World.

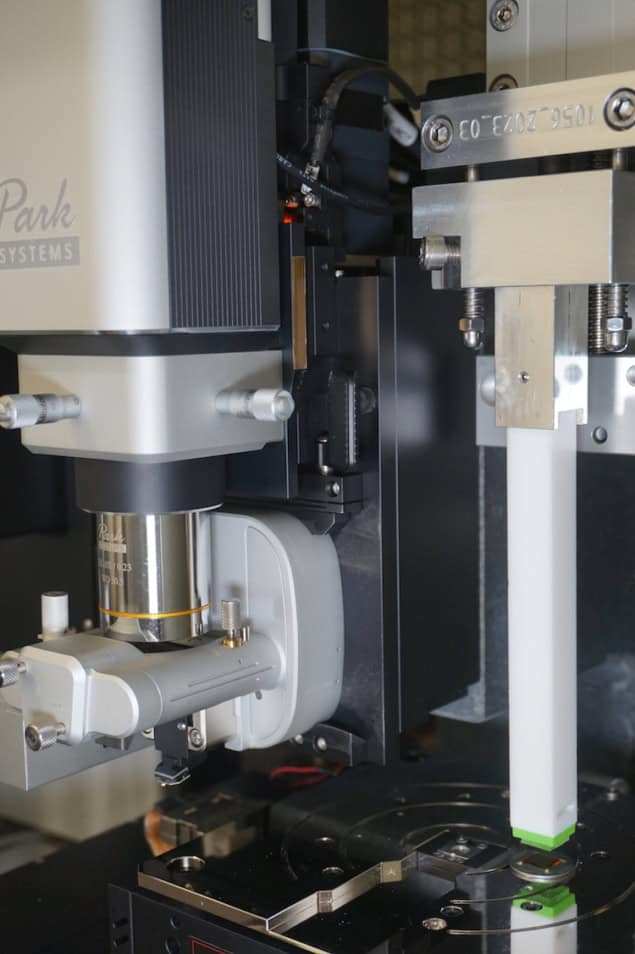

Static electricity is an everyday phenomenon, but it remains poorly understood. Researchers at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) have now shed new light on it by capturing an “image” of charge distributions as charge transfers from one surface to another. Their conclusions challenge longstanding interpretations of previous experiments and enhance our understanding of how charge behaves on insulating surfaces.

Static electricity is also known as contact electrification because it occurs when charge is transferred from one object to another by touch. The most common laboratory example involves rubbing a balloon on someone’s head to make their hair stand on end. However, static electricity is also associated with many other activities, including coffee grinding, pollen transport and perhaps even the formation of rocky planets.

One of the most useful ways of studying contact electrification is to move a metal tip slowly over the surface of a sample without touching it, recording a voltage all the while. These so-called scanning Kelvin methods produce an “image” of voltages created by the transferred charge. At the macroscale, around 100 μm to 10 cm, the main method is termed scanning Kelvin probe microscopy (SKPM). At the nanoscale, around 10 nm to 100 μm, a related but distinct variant known as Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) is used instead.

In previous fundamental physics studies using these techniques, the main challenges have been to make sense of the stationary patterns of charge left behind after contact electrification, and to investigate how these patterns evolve over space and time. In the latest work, the ISTA team chose to ask a slightly different question: when are the dynamics of charge transfer too fast for measured stationary patterns to yield meaningful information?

To find out, ISTA PhD student Felix Pertl built a special setup that could measure a sample’s surface charge with KPFM; transfer it below a linear actuator so that it could exchange charge when it contacted another material; and then transfer it underneath the KPFM again to image the resulting change in the surface charge.

“In a typical set-up, the sample transfer, moving the AFM to the right place and reinitiation and recalibration of the KPFM parameters can easily take as long as tens of minutes,” Pertl explains. “In our system, this happens in as little as around 30 s. As all aspects of the system are completely automated, we can repeat this process, and quickly, many times.”

This speed-up is important because static electricity dissipates relatively rapidly. In fact, the researchers found that the transferred charge disappeared from the sample’s surface quicker than the time required for most KPFM scans. Their data also revealed that the deposited charge was, in effect, uniformly distributed across the surface and that its dissipation depended on the material’s electrical conductivity. Additional mathematical modelling and subsequent experiments confirmed that the more insulating a material is, the slower it dissipates charge.

Pertl says that these results call into question the validity of some previous static electricity studies that used KPFM to study charge transfer. “The most influential paper in our field to date reported surface charge heterogeneity using KPFM,” he tells Physics World. At first, the ISTA team’s goal was to understand the origin of this heterogeneity. But when their own experiments showed an essentially homogenous distribution of surface charge, the researchers had to change tack.

“The biggest challenge in our work was realizing – and then accepting – that we could not reproduce the results from this previous study,” Pertl says. “Convincing both my principal investigator and myself that our data revealed a very different physical mechanism required patience, persistence and trust in our experimental approach.”

The discrepancy, he adds, implies that the surface heterogeneity previously observed was likely not a feature of static electricity, as was claimed. Instead, he says, it was probably “an artefact of the inability to image the charge before it had left the sample surface”.

Studies of contact electrification studies go back a long way. Philippe Molinié of France’s GeePs Laboratory, who was not involved in this work, notes that the first experiments were performed by the English scientist William Gilbert clear back in the sixteenth century. As well as coining the term “electricity” (from the Greek “elektra”, meaning amber), Gilbert was also the first to establish that magnets maintain their electrical attraction over time, while the forces produced by contact-charged insulators slowly decrease.

“Four centuries later, many mysteries remain unsolved in the contact electrification phenomenon,” Molinié observes. He adds that the surfaces of insulating materials are highly complex and usually strongly disordered, which affects their ability to transfer charge at the molecular scale. “The dynamics of the charge neutralization, as Pertl and colleagues underline, is also part of the process and is much more complex than could be described by a simple resistance-capacitor model,” Molinié says.

Although the ISTA team studied these phenomena with sophisticated Kelvin probe microscopy rather than the rudimentary tools available to Gilbert, it is, Molinié says, “striking that the competition between charge transfer and charge screening that comes from the conductivity of an insulator, first observed by Gilbert, is still at the very heart of the scientific interrogations that this interesting new work addresses.”

The Austrian researchers, who detail their work in Phys. Rev. Lett., say they hope their experiments will “encourage a more critical interpretation” of KPFM data in the future, with a new focus on the role of sample grounding and bulk conductivity in shaping observed charge patterns. “We hope it inspires KPFM users to reconsider how they design and analyse experiments, which could lead to more accurate insights into charge behaviour in insulators,” Pertl says.

“We are now planning to deliberately engineer surface charge heterogeneity into our samples,” he reveals. “By tuning specific surface properties, we aim to control the sign and spatial distribution of charge on defined regions of these.”

The post New experiments on static electricity cast doubt on previous studies in the field appeared first on Physics World.

“Global collaborations for European economic resilience” is the theme of SEMICON Europa 2025. The event is coming to Munich, Germany on 18–21 November and it will attract 25,000 semiconductor professionals who will enjoy presentations from over 200 speakers.

The TechARENA portion of the event will cover a wide range of technology-related issues including new materials, future computing paradigms and the development of hi-tech skills in the European workface. There will also be an Executive Forum, which will feature leaders in industry and government and will cover topics including silicon geopolitics and the use of artificial intelligence in semiconductor manufacturing.

SEMICON Europa will be held at the Messe München, where it will feature a huge exhibition with over 500 exhibitors from around the world. The exhibition is spread out over three halls and here are some of the companies and product innovations to look out for on the show floor.

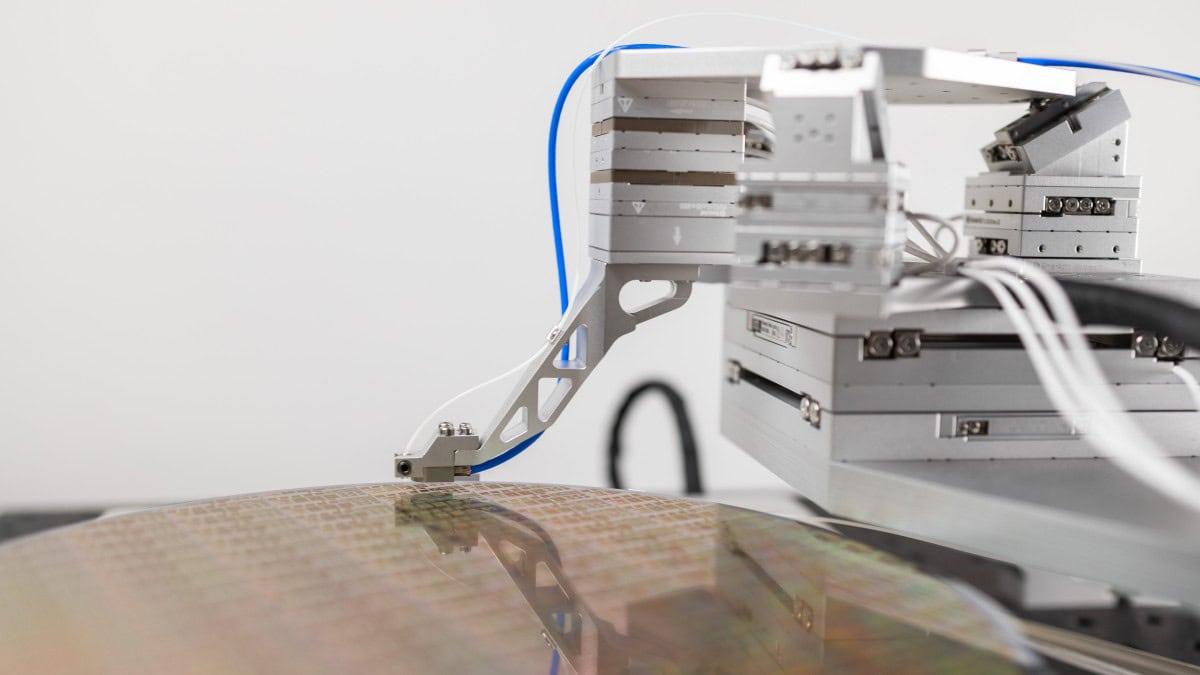

As the boundaries between electronic and photonic technologies continue to blur, the semiconductor industry faces a growing challenge: how to test and align increasingly complex electro-photonic chip architectures efficiently, precisely, and at scale. At SEMICON Europa 2025, SmarAct will address this challenge head-on with its latest innovation – Fast Scan Align. This is a high-speed and high-precision alignment solution that redefines the limits of testing and packaging for integrated photonics.

In the emerging era of heterogeneous integration, electronic and photonic components must be aligned and interconnected with sub-micrometre accuracy. Traditional positioning systems often struggle to deliver both speed and precision, especially when dealing with the delicate coupling between optical and electrical domains. SmarAct’s Fast Scan Align solution bridges this gap by combining modular motion platforms, real-time feedback control, and advanced metrology into one integrated system.

At its core, Fast Scan Align leverages SmarAct’s electromagnetic and piezo-driven positioning stages, which are capable of nanometre-resolution motion in multiple degrees of freedom. Fast Scan Align’s modular architecture allows users to configure systems tailored to their application – from wafer-level testing to fibre-to-chip alignment with active optical coupling. Integrated sensors and intelligent algorithms enable scanning and alignment routines that drastically reduce setup time while improving repeatability and process stability.

Fast Scan Align’s compact modules allow various measurement techniques to be integrated with unprecedented possibilities. This has become decisive for the increasing level of integration of complex electro-photonic chips.

Apart from the topics of wafer-level testing and packaging, wafer positioning with extreme precision is as crucial as never before for the highly integrated chips of the future. SmarAct’s PICOSCALE interferometer addresses the challenge of extreme position by delivering picometer-level displacement measurements directly at the point of interest.

When combined with SmarAct’s precision wafer stages, the PICOSCALE interferometer ensures highly accurate motion tracking and closed-loop control during dynamic alignment processes. This synergy between motion and metrology gives users unprecedented insight into the mechanical and optical behaviour of their devices – which is a critical advantage for high-yield testing of photonic and optoelectronic wafers.

Visitors to SEMICON Europa will also experience how all of SmarAct’s products – from motion and metrology components to modular systems and up to turn-key solutions – integrate seamlessly, offering intuitive operation, full automation capability, and compatibility with laboratory and production environments alike.

For more information visit SmarAct at booth B1.860 or explore more of SmarAct’s solutions in the semiconductor and photonics industry.

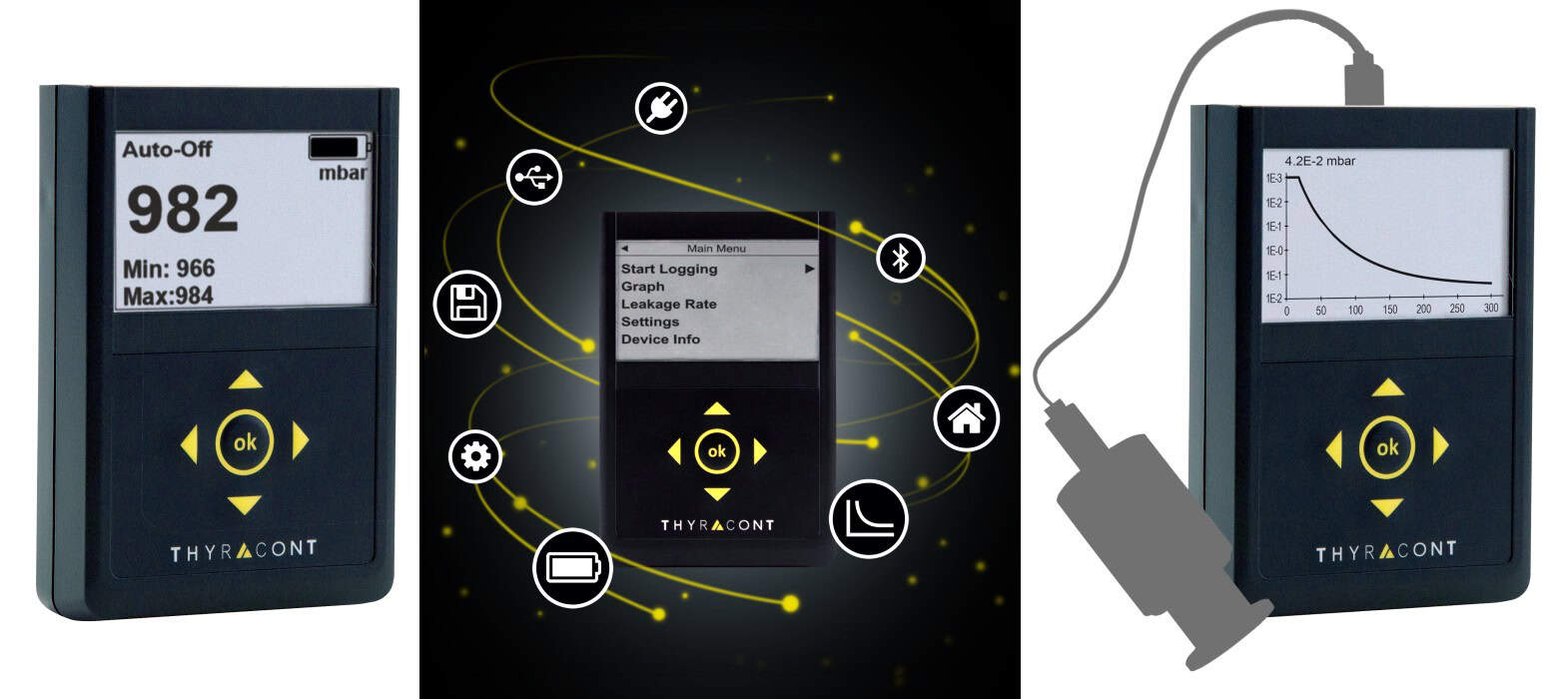

Thyracont Vacuum Instruments will be showcasing its precision vacuum metrology systems in exhibition hall C1. Made in Germany, the company’s broad portfolio combines diverse measurement technologies – including piezo, Pirani, capacitive, cold cathode, and hot cathode – to deliver reliable results across a pressure range from 2000 to 3e-11 mbar.

Front-and-centre at SEMICON Europa will be Thyracont’s new series of VD800 compact vacuum meters. These instruments provide precise, on-site pressure monitoring in industrial and research environments. Featuring a direct pressure display and real-time pressure graphs, the VD800 series is ideal for service and maintenance tasks, laboratory applications, and test setups.

The VD800 series combines high accuracy with a highly intuitive user interface. This delivers real-time measurement values; pressure diagrams; and minimum and maximum pressure – all at a glance. The VD800’s 4+1 membrane keypad ensures quick access to all functions. USB-C and optional Bluetooth LE connectivity deliver seamless data readout and export. The VD800’s large internal data logger can store over 10 million measured values with their RTC data, with each measurement series saved as a separate file.

Data sampling rates can be set from 20 ms to 60 s to achieve dynamic pressure tracking or long-term measurements. Leak rates can be measured directly by monitoring the rise in pressure in the vacuum system. Intelligent energy management gives the meters extended battery life and longer operation times. Battery charging is done conveniently via USB-C.

The vacuum meters are available in several different sensor configurations, making them adaptable to a wide range of different uses. Model VD810 integrates a piezo ceramic sensor for making gas-type-independent measurements for rough vacuum applications. This sensor is insensitive to contamination, making it suitable for rough industrial environments. The VD810 measures absolute pressure from 2000 to 1 mbar and relative pressure from −1060 to +1200 mbar.

Model VD850 integrates a piezo/Pirani combination sensor, which delivers high resolution and accuracy in the rough and fine vacuum ranges. Optimized temperature compensation ensures stable measurements in the absolute pressure range from 1200 to 5e-5 mbar and in the relative pressure range from −1060 to +340 mbar.

The model VD800 is a standalone meter designed for use with Thyracont’s USB-C vacuum transducers, which are available in two models. The VSRUSB USB-C transducer is a piezo/Pirani combination sensor that measures absolute pressure in the 2000 to 5.0e-5 mbar range. The other is the VSCUSB USB-C transducer, which measures absolute pressures from 2000 down to 1 mbar and has a relative pressure range from -1060 to +1200 mbar. A USB-C cable connects the transducer to the VD800 for quick and easy data retrieval. The USB-C transducers are ideal for hard-to-reach areas of vacuum systems. The transducers can be activated while a process is running, enabling continuous monitoring and improved service diagnostics.

With its blend of precision, flexibility, and ease of use, the Thyracont VD800 series defines the next generation of compact vacuum meters. The devices’ intuitive interface, extensive data capabilities, and modern connectivity make them an indispensable tool for laboratories, service engineers, and industrial operators alike.

To experience the future of vacuum metrology in Munich, visit Thyracont at SEMICON Europa hall C1, booth 752. There you will discover how the VD800 series can optimize your pressure monitoring workflows.

The post SEMICON Europa 2025 presents cutting-edge technology for semiconductor R&D and production appeared first on Physics World.

IOP Publishing’s Machine Learning series is the world’s first open-access journal series dedicated to the application and development of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) for the sciences.

Part of the series is Machine Learning: Science and Technology, launched in 2019, which bridges the application and advances in machine learning across the sciences. Machine Learning: Earth is dedicated to the application of ML and AI across all areas of Earth, environmental and climate sciences while Machine Learning: Health covers healthcare, medical, biological, clinical and health sciences and Machine Learning: Engineeringfocuses on applied AI and non-traditional machine learning to the most complex engineering challenges.

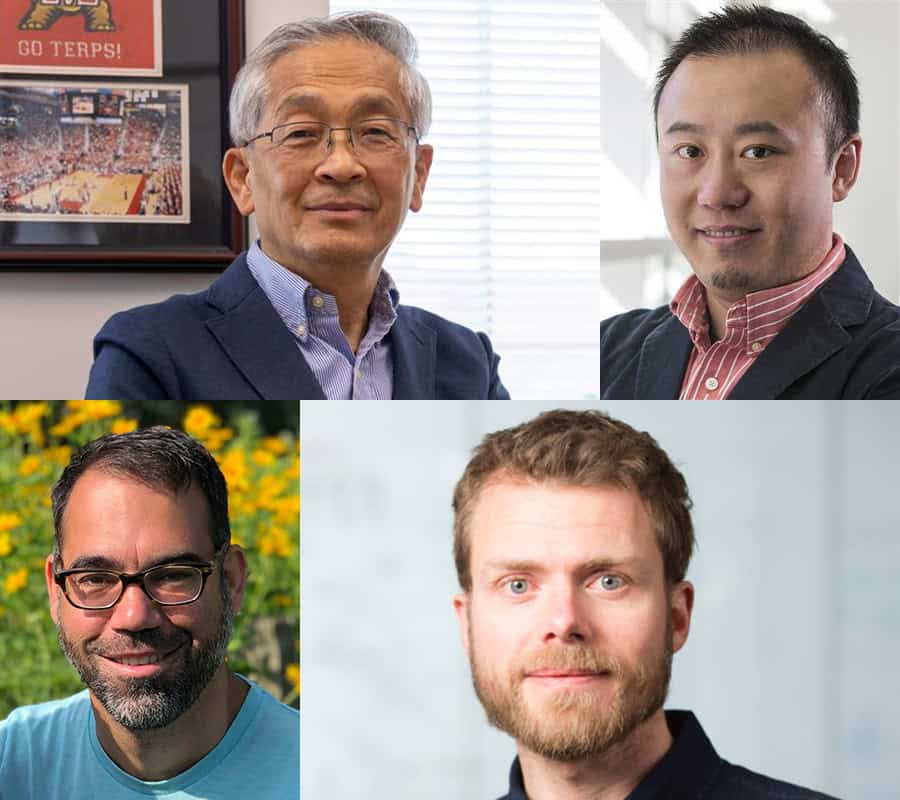

Here, the editors-in-chief (EiC) of the four journals discuss the growing importance of machine learning and their plans for the future.

Kyle Cranmer is a particle physicist and data scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is EiC of Machine Learning: Science and Technology (MLST). Pierre Gentine is a geophysicist at Columbia University and is EiC of Machine Learning: Earth. Jimeng Sun is a biophysicist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and is EiC of Machine Learning: Health. Mechanical engineer Jay Lee is from the University of Maryland and is EiC of Machine Learning: Engineering.

Kyle Cranmer (KC): It is due to a convergence of multiple factors. The initial success of deep learning was driven largely by benchmark datasets, advances in computing with graphics processing units, and some clever algorithmic tricks. Since then, we’ve seen a huge investment in powerful, easy-to-use tools that have dramatically lowered the barrier to entry and driven extraordinary progress.

Pierre Gentine (PG): Machine learning has been transforming many fields of physics, as it can accelerate physics simulation, better handle diverse sources of data (multimodality), help us better predict.

Jimeng Sun (JS): Over the past decade, we have seen machine learning models consistently reach — and in some cases surpass — human-level performance on real-world tasks. This is not just in benchmark datasets, but in areas that directly impact operational efficiency and accuracy, such as medical imaging interpretation, clinical documentation, and speech recognition. Once ML proved it could perform reliably at human levels, many domains recognized its potential to transform labour-intensive processes.

Jay Lee (JL): Traditionally, ML growth is based on the development of three elements: algorithms, big data, and computing. The past decade’s growth in ML research is due to the perfect storm of abundant data, powerful computing, open tools, commercial incentives, and groundbreaking discoveries—all occurring in a highly interconnected global ecosystem.

KC: The advances in generative AI and self-supervised learning are very exciting. By generative AI, I don’t mean Large Language Models — though those are exciting too — but probabilistic ML models that can be useful in a huge number of scientific applications. The advances in self-supervised learning also allows us to engage our imagination of the potential uses of ML beyond well-understood supervised learning tasks.

PG: I am very interested in the use of ML for climate simulations and fluid dynamics simulations.

JS: The emergence of agentic systems in healthcare — AI systems that can reason, plan, and interact with humans to accomplish complex goals. A compelling example is in clinical trial workflow optimization. An agentic AI could help coordinate protocol development, automatically identify eligible patients, monitor recruitment progress, and even suggest adaptive changes to trial design based on interim data. This isn’t about replacing human judgment — it’s about creating intelligent collaborators that amplify expertise, improve efficiency, and ultimately accelerate the path from research to patient benefit.

JL: One area is generative and multimodal ML — integrating text, images, video, and more — are transforming human–AI interaction, robotics, and autonomous systems. Equally exciting is applying ML to nontraditional domains like semiconductor fabs, smart grids, and electric vehicles, where complex engineering systems demand new kinds of intelligence.

KC: The need for a venue to propagate advances in AI/ML in the sciences is clear. The large AI conferences are under stress, and their review system is designed to be a filter not a mechanism to ensure quality, improve clarity and disseminate progress. The large AI conferences also aren’t very welcoming to user-inspired research, often casting that work as purely applied. Similarly, innovation in AI/ML often takes a back seat in physics journals, which slows the propagation of those ideas to other fields. My vision for MLST is to fill this gap and nurture the community that embraces AI/ML research inspired by the physical sciences.

PG: I hope we can demonstrate that machine learning is more than a nice tool but that it can play a fundamental role in physics and Earth sciences, especially when it comes to better simulating and understanding the world.

JS: I see Machine Learning: Health becoming the premier venue for rigorous ML–health research — a place where technical novelty and genuine clinical impact go hand in hand. We want to publish work that not only advances algorithms but also demonstrates clear value in improving health outcomes and healthcare delivery. Equally important, we aim to champion open and reproducible science. That means encouraging authors to share code, data, and benchmarks whenever possible, and setting high standards for transparency in methods and reporting. By doing so, we can accelerate the pace of discovery, foster trust in AI systems, and ensure that our field’s breakthroughs are accessible to — and verifiable by — the global community.

JL: Machine Learning: Engineering envisions becoming the global platform where ML meets engineering. By fostering collaboration, ensuring rigour and interpretability, and focusing on real-world impact, we aim to redefine how AI addresses humanity’s most complex engineering challenges.

The post Physicists discuss the future of machine learning and artificial intelligence appeared first on Physics World.

Games played under the laws of quantum mechanics dissipate less energy than their classical equivalents. This is the finding of researchers at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU), who worked with colleagues in the UK, Austria and the US to apply the mathematics of game theory to quantum information. The researchers also found that for more complex game strategies, the quantum-classical energy difference can increase without bound, raising the possibility of a “quantum advantage” in energy dissipation.

Game theory is the field of mathematics that aims to formally understand the payoff or gains that a person or other entity (usually called an agent) will get from following a certain strategy. Concepts from game theory are often applied to studies of quantum information, especially when trying to understand whether agents who can use the laws of quantum physics can achieve a better payoff in the game.

In the latest work, which is published in Physical Review Letters, Jayne Thompson, Mile Gu and colleagues approached the problem from a different direction. Rather than focusing on differences in payoffs, they asked how much energy must be dissipated to achieve identical payoffs for games played under the laws of classical versus quantum physics. In doing so, they were guided by Landauer’s principle, an important concept in thermodynamics and information theory that states that there is a minimum energy cost to erasing a piece of information.

This Landauer minimum is known to hold for both classical and quantum systems. However, in practice systems will spend more than the minimum energy erasing memory to make space for new information, and this energy will be dissipated as heat. What the NTU team showed is that this extra heat dissipation can be reduced in the quantum system compared to the classical one.

To understand why, consider that when a classical agent creates a strategy, it must plan for all possible future contingencies. This means it stores possibilities that never occur, wasting resources. Thompson explains this with a simple analogy. Suppose you are packing to go on a day out. Because you are not sure what the weather is going to be, you must pack items to cover all possible weather outcomes. If it’s sunny, you’d like sunglasses. If it rains, you’ll need your umbrella. But if you only end up using one of these items, you’ll have wasted space in your bag.

“It turns out that the same principle applies to information,” explains Thompson. “Depending on future outcomes, some stored information may turn out to be unnecessary – yet an agent must still maintain it to stay ready for any contingency.”

For a classical system, this can be a very wasteful process. Quantum systems, however, can use superposition to store past information more efficiently. When systems in a quantum superposition are measured, they probabilistically reveal an outcome associated with only one of the states in the superposition. Hence, while superposition can be used to store both pasts, upon measurement all excess information is automatically erased “almost as if they had never stored this information at all,” Thompson explains.

The upshot is that because information erasure has close ties to energy dissipation, this gives quantum systems an energetic advantage. “This is a fantastic result focusing on the physical aspect that many other approaches neglect,” says Vlatko Vedral, a physicist at the University of Oxford, UK who was not involved in the research.

Gu and Thompson say their result could have implications for the large language models (LLMs) behind popular AI tools such as ChatGPT, as it suggests there might be theoretical advantages, from an energy consumption point of view, in using quantum computers to run them.

Another, more foundational question they hope to understand regarding LLMs is the inherent asymmetry in their behaviour. “It is likely a lot more difficult for an LLM to write a book from back cover to front cover, as opposed to in the more conventional temporal order,” Thompson notes. When considered from an information-theoretic point of view, the two tasks are equivalent, making this asymmetry somewhat surprising.

In Thompson and Gu’s view, taking waste into consideration could shed light on this asymmetry. “It is likely we have to waste more information to go in one direction over the other,” Thompson says, “and we have some tools here which could be used to analyse this”.

For Vedral, the result also has philosophical implications. If quantum agents are more optimal, he says, it is “surely is telling us that the most coherent picture of the universe is the one where the agents are also quantum and not just the underlying processes that they observe”.

The post Playing games by the quantum rulebook expends less energy appeared first on Physics World.

Complex systems model real-world behaviour that is dynamic and often unpredictable. They are challenging to simulate because of nonlinearity, where small changes in conditions can lead to disproportionately large effects; many interacting variables, which make computational modelling cumbersome; and randomness, where outcomes are probabilistic. Machine learning is a powerful tool for understanding complex systems. It can be used to find hidden relationships in high-dimensional data and predict the future state of a system based on previous data.

This research develops a novel machine learning approach for complex systems that allows the user to extract a few collective descriptors of the system, referred to as inherent structural variables. The researchers used an autoencoder (a type of machine learning tool) to examine snapshots of how atoms are arranged in a system at any moment (called instantaneous atomic configurations). Each snapshot is then matched to a more stable version of that structure (an inherent structure), which represents the system’s underlying shape or pattern after thermal noise is removed. These inherent structural variables enable the analysis of structural transitions both in and out of equilibrium and the computation of high-resolution free-energy landscapes. These are detailed maps that show how a system’s energy changes as its structure or configuration changes, helping researchers understand stability, transitions, and dynamics in complex systems.

The model is versatile, and the authors demonstrate how it can be applied to metal nanoclusters and protein structures. In the case of Au147 nanoclusters (well-organised structures made up of 147 gold atoms), the inherent structural variables reveal three main types of stable structures that the gold nanocluster can adopt: fcc (face-centred cubic), Dh (decahedral), and Ih (icosahedral). These structures represent different stable states that a nanocluster can switch between, and on the high-resolution free-energy landscape, they appear as valleys. Moving from one valley to another isn’t easy, there are narrow paths or barriers between them, known as kinetic bottlenecks.

The researchers validated their machine learning model using Markov state models, which are mathematical tools that help analyse how a system moves between different states over time, and electron microscopy, which images atomic structures and can confirm that the predicted structures exist in the gold nanoclusters. The approach also captures non-equilibrium melting and freezing processes, offering insights into polymorph selection and metastable states. Scalability is demonstrated up to Au309 clusters.

The generality of the method is further demonstrated by applying it to the bradykinin peptide, a completely different type of system, identifying distinct structural motifs and transitions. Applying the method to a biological molecule provides further evidence that the machine learning approach is a flexible, powerful technique for studying many kinds of complex systems. This work contributes to machine learning strategies, as well as experimental and theoretical studies of complex systems, with potential applications across liquids, glasses, colloids, and biomolecules.

Inherent structural descriptors via machine learning

Emanuele Telari et al 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 068002

Complex systems in the spotlight: next steps after the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics by Ginestra Bianconi et al (2023)

The post Teaching machines to understand complexity appeared first on Physics World.

The Standard Model of particle physics is a very well-tested theory that describes the fundamental particles and their interactions. However, it does have several key limitations. For example, it doesn’t account for dark matter or why neutrinos have masses.

One of the main aims of experimental particle physics at the moment is therefore to search for signs of new physical phenomena beyond the Standard Model.

Finding something new like this would point us towards a better theoretical model of particle physics: one that can explain things that the Standard Model isn’t able to.

These searches often involve looking for rare or unexpected signals in high-energy particle collisions such as those at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

In a new paper published by the CMS collaboration, a new analysis method was used to search for new particles produced by proton-proton collisions at the at the LHC.

These particles would decay into two jets, but with unusual internal structure not typical of known particles like quarks or gluons.

The researchers used advanced machine learning techniques to identify jets with different substructures, applying various anomaly detection methods to maximise sensitivity to unknown signals.

Unlike traditional strategies, anomaly detection methods allow the AI models to identify anomalous patterns in the data without being provided specific simulated examples, giving them increased sensitivity to a wider range of potential new particles.

This time, they didn’t find any significant deviations from expected background values. Although no new particles were found, the results enabled the team to put several new theoretical models to the test for the first time. They were also able to set upper bounds on the production rates of several hypothetical particles.

Most importantly, the study demonstrates that machine learning can significantly enhance the sensitivity of searches for new physics, offering a powerful tool for future discoveries at the LHC.

The CMS Collaboration, 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 067802

The post Using AI to find new particles at the LHC appeared first on Physics World.

Classical clocks have to obey the second law of thermodynamics: the higher their precision, the more entropy they produce. For a while, it seemed like quantum clocks might beat this system, at least in theory. This is because although quantum fluctuations produce no entropy, if you can count those fluctuations as clock “ticks”, you can make a clock with nonzero precision. Now, however, a collaboration of researchers across Europe has pinned down where the entropy-precision trade-off balances out: it’s in the measurement process. As project leader Natalia Ares observes, “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.”

The clock the team used to demonstrate this principle consists of a pair of quantum dots coupled by a thin tunnelling barrier. In this double quantum dot system, a “tick” occurs whenever an electron tunnels from one side of the system to the other, through both dots. Applying a bias voltage gives ticks a preferred direction.

This might not seem like the most obvious kind of clock. Indeed, as an actual timekeeping device, collaboration member Florian Meier describes it as “quite bad”. However, Ares points out that although the tunnelling process is random (stochastic), the period between ticks does have a mean and a standard deviation. Hence, given enough ticks, the number of ticks recorded will tell you something about how much time has passed.

In any case, Meier adds, they were not setting out to build the most accurate clock. Instead, they wanted to build a playground to explore basic principles of energy dissipation and clock precision, and for that, it works really well. “The really cool thing I like about what they did was that with that particular setup, you can really pinpoint the entropy dissipation of the measurement somehow in this quantum dot,” says Meier, a PhD student at the Technical University in Vienna, Austria. “I think that’s really unique in the field.”

To measure the entropy of each quantum tick, the researchers measured the voltage drop (and associated heat dissipation) for each electron tunnelling through the double quantum dot. Vivek Wadhia, a DPhil student in Ares’s lab at the University of Oxford, UK who performed many of the measurements, points out that this single unit of charge does not equate to very much entropy. However, measuring the entropy of the tunnelling electron was not the full story.

Because the ticks of the quantum clock were, in effect, continuously monitored by the environment, the coherence time for each quantum tunnelling event was very short. However, because the time on this clock could not be observed directly by humans – unlike, say, the hands of a mechanical clock – the researchers needed another way to measure and record each tick.

For this, they turned to the electronics they were using in the lab and compared the power in versus the power out on a macroscopic scale. “That’s the cost of our measurement, right?” says Wadhia, adding that this cost includes both the measuring and recording of each tick. He stresses that they were not trying to find the most thermodynamically efficient measurement technique: “The idea was to understand how the readout compares to the clockwork.”

This classical entropy associated with measuring and recording each tick turns out to be nine orders of magnitude larger than the quantum entropy of a tick – more than enough for the system to operate as a clock with some level of precision. “The interesting thing is that such simple systems sometimes reveal how you can maybe improve precision at a very low cost thermodynamically,” Meier says.

As a next step, Ares plans to explore different arrangements of quantum dots, using Meier’s previous theoretical work to improve the clock’s precision. “We know that, for example, clocks in nature are not that energy intensive,” Ares tells Physics World. “So clearly, for biology, it is possible to run a lot of processes with stochastic clocks.”

The research is reported in Physical Review Letters.

The post Researchers pin down the true cost of precision in quantum clocks appeared first on Physics World.

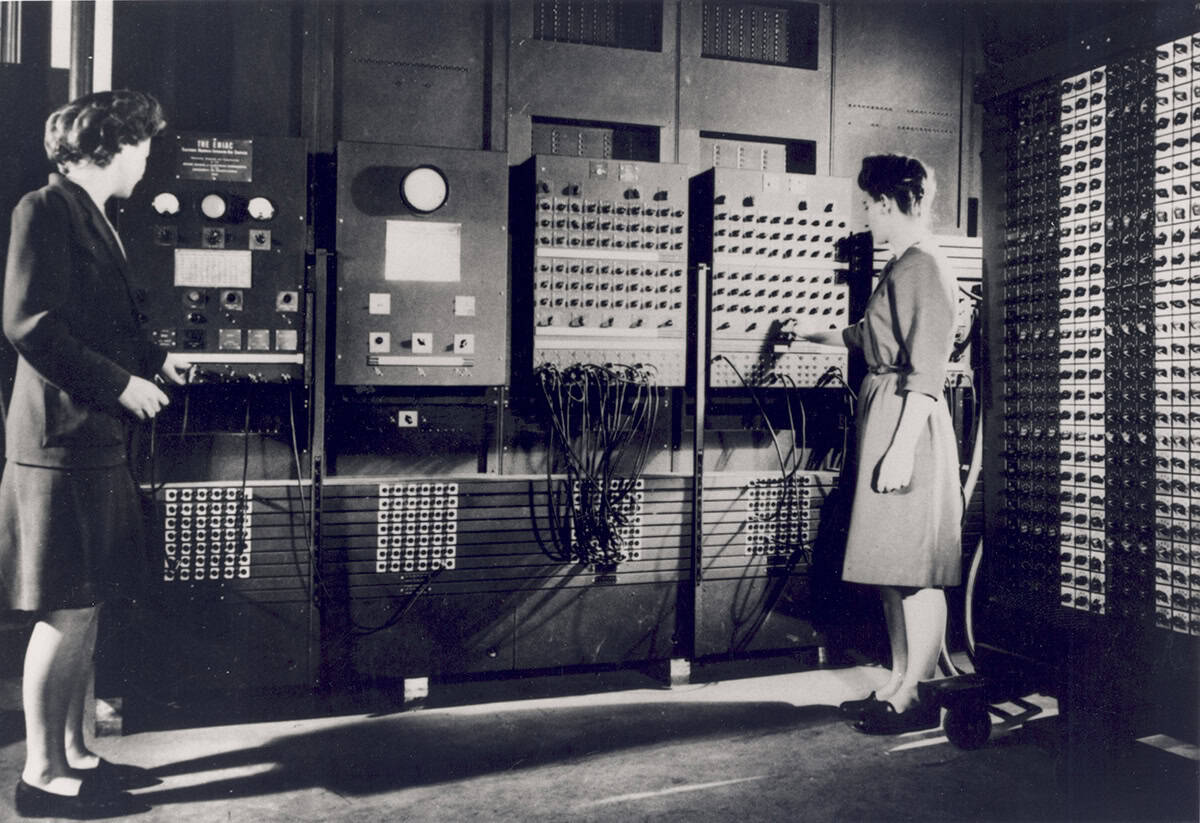

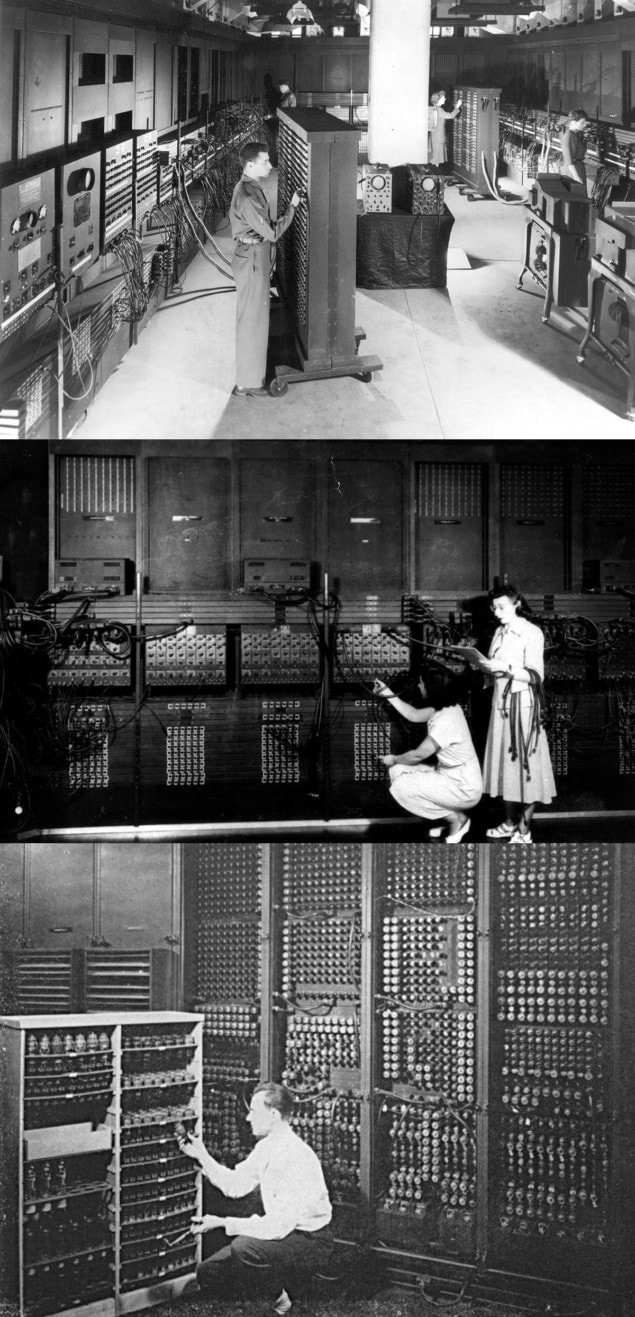

When you look back at the early days of computing, some familiar names pop up, including John von Neumann, Nicholas Metropolis and Richard Feynman. But they were not lonely pioneers – they were part of a much larger group, using mechanical and then electronic computers to do calculations that had never been possible before.

These people, many of whom were women, were the first scientific programmers and computational scientists. Skilled in the complicated operation of early computing devices, they often had degrees in maths or science, and were an integral part of research efforts. And yet, their fundamental contributions are mostly forgotten.

This was in part because of their gender – it was an age when sexism was rife, and it was standard for women to be fired from their job after getting married. However, there is another important factor that is often overlooked, even in today’s scientific community – people in technical roles are often underappreciated and underacknowledged, even though they are the ones who make research possible.

Originally, a “computer” was a human being who did calculations by hand or with the help of a mechanical calculator. It is thought that the world’s first computational lab was set up in 1937 at Columbia University. But it wasn’t until the Second World War that the demand for computation really exploded; with the need for artillery calculations, new technologies and code breaking.

In the US, the development of the atomic bomb during the Manhattan Project (established in 1943) required huge computational efforts, so it wasn’t long before the New Mexico site had a hand-computing group. Called the T-5 group of the Theoretical Division, it initially consisted of about 20 people. Most were women, including the spouses of other scientific staff. Among them was Mary Frankel, a mathematician married to physicist Stan Frankel; mathematician Augusta “Mici” Teller who was married to Edward Teller, the “father of the hydrogen bomb”; and Jean Bacher, the wife of physicist Robert Bacher.

As the war continued, the T-5 group expanded to include civilian recruits from the nearby towns and members of the Women’s Army Corps. Its staff worked around the clock, using printed mathematical tables and desk calculators in four-hour shifts – but that was not enough to keep up with the computational needs for bomb development. In the early spring of 1944, IBM punch-card machines were brought in to supplement the human power. They became so effective that the machines were soon being used for all large calculations, 24 hours a day, in three shifts.

The computational group continued to grow, and among the new recruits were Naomi Livesay and Eleonor Ewing. Livesay held an advanced degree in mathematics and had done a course in operating and programming IBM electric calculating machines, making her an ideal candidate for the T-5 division. She in turn recruited Ewing, a fellow mathematician who was a former colleague. The two young women supervised the running of the IBM machines around the clock.

The frantic pace of the T-5 group continued until the end of the war in September 1945. The development of the atomic bomb required an immense computational effort, which was made possible through hand and punch-card calculations.

Shortly after the war ended, the first fully electronic, general-purpose computer – the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) – became operational at the University of Pennsylvania, following two years of development. The project had been led by physicist John Mauchly and electrical engineer J Presper Eckert. The machine was operated and coded by six women – mathematicians Betty Jean Jennings (later Bartik); Kathleen, or Kay, McNulty (later Mauchly, then Antonelli); Frances Bilas (Spence); Marlyn Wescoff (Meltzer) and Ruth Lichterman (Teitelbaum); as well as Betty Snyder (Holberton) who had studied journalism.

Polymath John von Neumann also got involved when looking for more computing power for projects at the new Los Alamos Laboratory, established in New Mexico in 1947. In fact, although originally designed to solve ballistic trajectory problems, the first problem to be run on the ENIAC was “the Los Alamos problem” – a thermonuclear feasibility calculation for Teller’s group studying the H-bomb.

Like in the Manhattan Project, several husband-and-wife teams worked on the ENIAC, the most famous being von Neumann and his wife Klara Dán, and mathematicians Adele and Herman Goldstine. Dán von Neumann in particular worked closely with Nicholas Metropolis, who alongside mathematician Stanislaw Ulam had coined the term Monte Carlo to describe numerical methods based on random sampling. Indeed, between 1948 and 1949 Dán von Neumann and Metropolis ran the first series of Monte Carlo simulations on an electronic computer.

Work began on a new machine at Los Alamos in 1948 – the Mathematical Analyzer Numerical Integrator and Automatic Computer (MANIAC) – which ran its first large-scale hydrodynamic calculation in March 1952. Many of its users were physicists, and its operators and coders included mathematicians Mary Tsingou (later Tsingou-Menzel), Marjorie Jones (Devaney) and Elaine Felix (Alei); plus Verna Ellingson (later Gardiner) and Lois Cook (Leurgans).

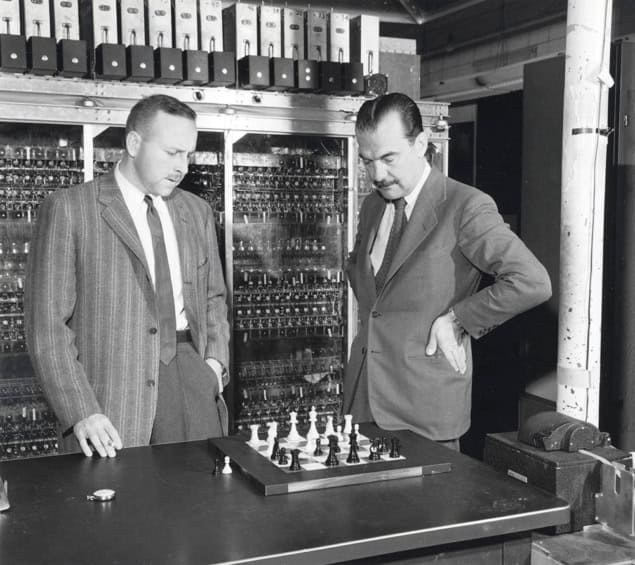

The Los Alamos scientists tried all sorts of problems on the MANIAC, including a chess-playing program – the first documented case of a machine defeating a human at the game. However, two of these projects stand out because they had profound implications on computational science.

In 1953 the Tellers, together with Metropolis and physicists Arianna and Marshall Rosenbluth, published the seminal article “Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines” (J. Chem. Phys. 21 1087). The work introduced the ideas behind the “Metropolis (later renamed Metropolis–Hastings) algorithm”, which is a Monte Carlo method that is based on the concept of “importance sampling”. (While Metropolis was involved in the development of Monte Carlo methods, it appears that he did not contribute directly to the article, but provided access to the MANIAC nightshift.) This is the progenitor of the Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods, which are widely used today throughout science and engineering.

Marshall later recalled how the research came about when he and Arianna had proposed using the MANIAC to study how solids melt (AIP Conf. Proc. 690 22).

Edward Teller meanwhile had the idea of using statistical mechanics and taking ensemble averages instead of following detailed kinematics for each individual disk, and Mici helped with programming during the initial stages. However, the Rosenbluths did most of the work, with Arianna translating and programming the concepts into an algorithm.

The 1953 article is remarkable, not only because it led to the Metropolis algorithm, but also as one of the earliest examples of using a digital computer to simulate a physical system. The main innovation of this work was in developing “importance sampling”. Instead of sampling from random configurations, it samples with a bias toward physically important configurations which contribute more towards the integral.

Furthermore, the article also introduced another computational trick, known as “periodic boundary conditions” (PBCs): a set of conditions which are often used to approximate an infinitely large system by using a small part known as a “unit cell”. Both importance sampling and PBCs went on to become workhorse methods in computational physics.

In the summer of 1953, physicist Enrico Fermi, Ulam, Tsingou and physicist John Pasta also made a significant breakthrough using the MANIAC. They ran a “numerical experiment” as part of a series meant to illustrate possible uses of electronic computers in studying various physical phenomena.

The team modelled a 1D chain of oscillators with a small nonlinearity to see if it would behave as hypothesized, reaching an equilibrium with the energy redistributed equally across the modes (doi.org/10.2172/4376203). However, their work showed that this was not guaranteed for small perturbations – a non-trivial and non-intuitive observation that would not have been apparent without the simulations. It is the first example of a physics discovery made not by theoretical or experimental means, but through a computational approach. It would later lead to the discovery of solitons and integrable models, the development of chaos theory, and a deeper understanding of ergodic limits.