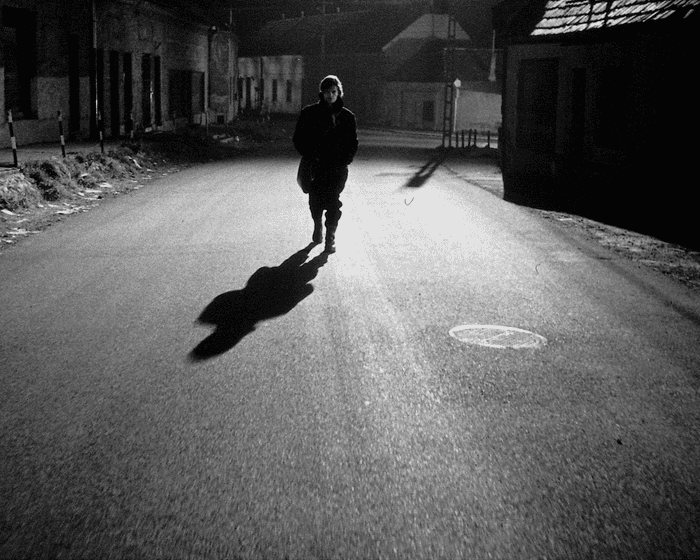

With Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies, Béla Tarr became the vividly disquieting master of spiritual desolation

The Hungarian director’s films moved slowly like vast gothic aircraft carrier-sized ships across dark seas, giving audiences a feeling of drunkenness and hangover at the same time

• Béla Tarr, Hungarian director of Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies, dies aged 70

The semi-official genre of “slow cinema” has been around for decades: glacial pacing, unhurried and unbroken takes, static shooting positions, characters who appear to be looking – often wordlessly and unsmilingly – at people or things off camera or into the lens itself, mimicking the camera’s own calmly relentless gaze, the immobile silence accumulating into a transcendental simplicity. Robert Bresson, Theo Angelopoulos, Joe Weerasethakul, Lav Diaz, Lisandro Alonso; these are all great slow cinema practitioners. But surely no film-maker ever got the speedometer needle further back to the left than the tragicomic master Béla Tarr; his pace was less than zero, a kind of intense and monolithic slowness, an uber-slowness, in films that moved, often almost infinitesimally, like vast gothic aircraft-carrier-sized ships across dark seas.

Audience reactions were often a kind of delirium or incredulity at just how punishing the anti-pace was, but – given sufficient investment of attention – you found yourself responding with awe, but also laughing along to the macabre dark comedy, the parable and the satire. A Béla Tarr movie gave you drunkenness and hangover at the same time. And people were often to be found getting despairingly drunk in his films.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Courtesy: Curzon

© Photograph: Courtesy: Curzon

© Photograph: Courtesy: Curzon