OM : “aucun doute que Tochukwu Nnadi gagnera le coeur des supporters”… Qu’attendre de la recrue surprise du mercato ?

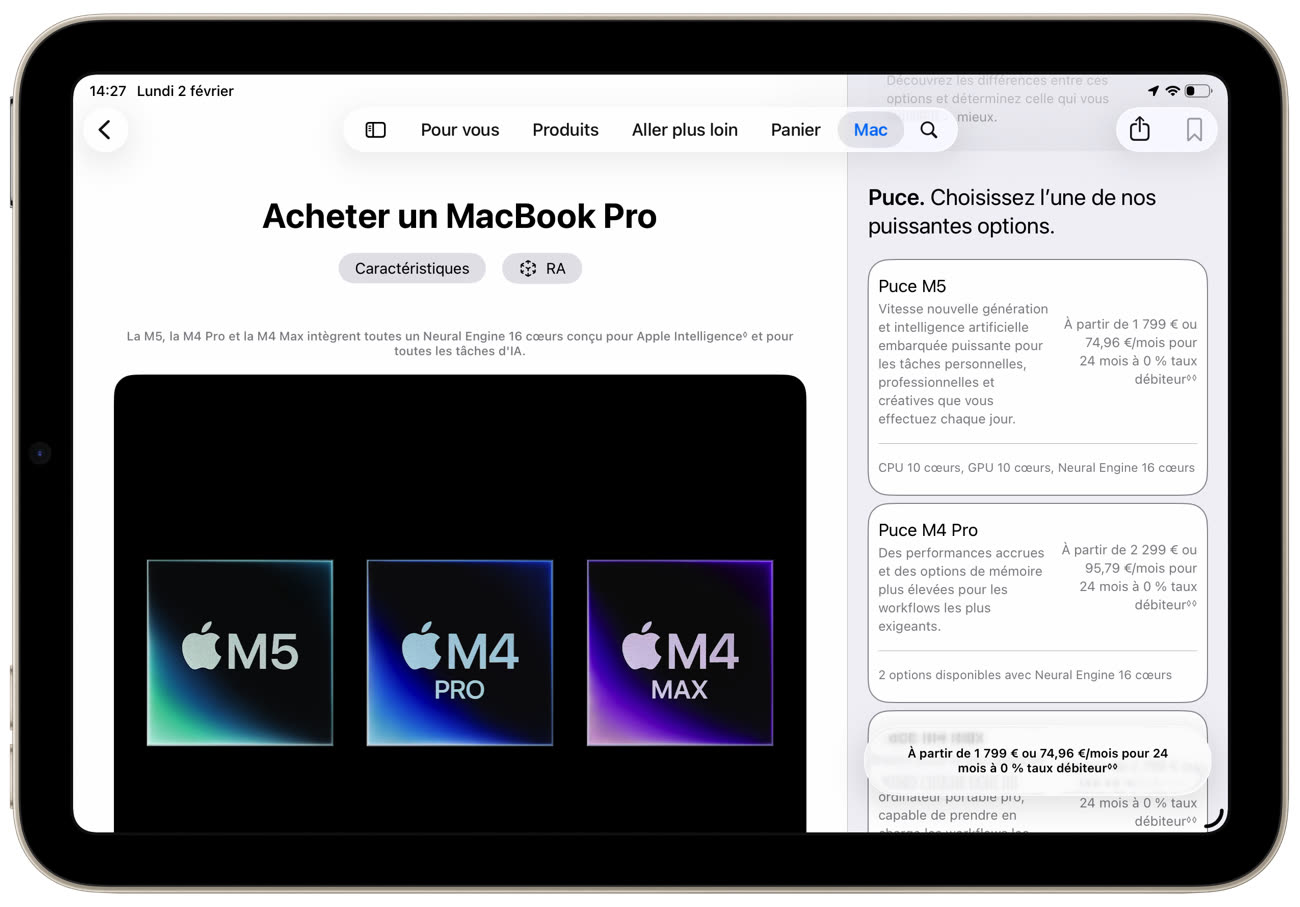

Depuis ce week-end, Apple a complètement revu le processus d’achat d’un Mac sur l’Apple Store. Il n’y a plus de configurations standards, il faut désormais composer soi-même sa machine, de la taille de l’écran jusqu’à la capacité de stockage. Un changement opéré en amont de l’arrivée des MacBook Pro M5 Pro et M5 Max afin d’offrir davantage de souplesse ? Ce n’est qu’une hypothèse, mais elle mérite d’être posée.

Les MacBook Pro M5 Pro et M5 Max pourraient en effet inaugurer des systèmes sur puce plus modulaires. Alors que la M5 standard reste une puce monolithique gravée en 3 nm, ses déclinaisons plus puissantes pourraient exploiter une nouvelle technologie permettant d’assembler au sein d’un même package plusieurs blocs distincts (CPU, GPU…) pas nécessairement gravés selon le même procédé.

Cette architecture modulaire présente plusieurs avantages : elle simplifie la conception, en permettant par exemple de réutiliser ou de dupliquer certains blocs pour créer différentes configurations. Elle améliore aussi les rendements de production et ouvre la voie à une segmentation plus fine de la gamme. De quoi imaginer un éventail de configurations plus large pour ces futures puces.

Avec les M5 Pro, Apple pourrait séparer CPU et GPU dans une conception 3D

Le nouveau configurateur de l’Apple Store semble aller dans ce sens. Plutôt que de pousser quelques modèles prédéfinis, Apple invite désormais les acheteurs à faire leurs propres choix. Pour les prochains MacBook Pro, on peut ainsi imaginer l’apparition d’un sous-menu permettant de sélectionner différents couples CPU/GPU. L’ancienne présentation ne rendait pas cela impossible, mais le nouveau configurateur s’accorde mieux avec cette logique.

Si cette évolution se confirme, une autre question se pose : avec un choix plus libre des composants, la distinction entre M5 Pro et M5 Max a-t-elle encore vocation à exister, ou ces deux puces pourraient-elles devenir les déclinaisons d’une même base « pro » hautement personnalisable ? On devrait en savoir plus dans les prochaines semaines, autour de la sortie de macOS 26.3, une version à laquelle les futurs MacBook Pro semblent étroitement liés.

Apple Store : acheter un Mac n’a jamais autant ressemblé à l’achat d’un iPhone

La version rafraichie des processeurs Arrow Lake S fait de nouveau parler d’elle. Cette fois, c’est le potentiel Core Ultra 9 290K qui montre les muscles avec des gains, en monocœur comme en multicœur, supérieurs de plus de 10% avec son grand frère le Core Ultra 9 285K sous Geekbench. Core Ultra 9 290k : […]

L’article Le Core Ultra 9 290K se montre une nouvelle fois en forme est apparu en premier sur Overclocking.com.

© « Le Monde »

© « Le Monde »

© Eric Lee/The New York Times

© Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

Amiens devrait accueillir quatre joueurs ce lundi : après Yoan Koré, Ibou Sané, Samuel Ntamack et Skelly Alvero pourraient être ceux-ci.

Amiens devrait accueillir quatre joueurs ce lundi : après Yoan Koré, Ibou Sané, Samuel Ntamack et Skelly Alvero pourraient être ceux-ci.

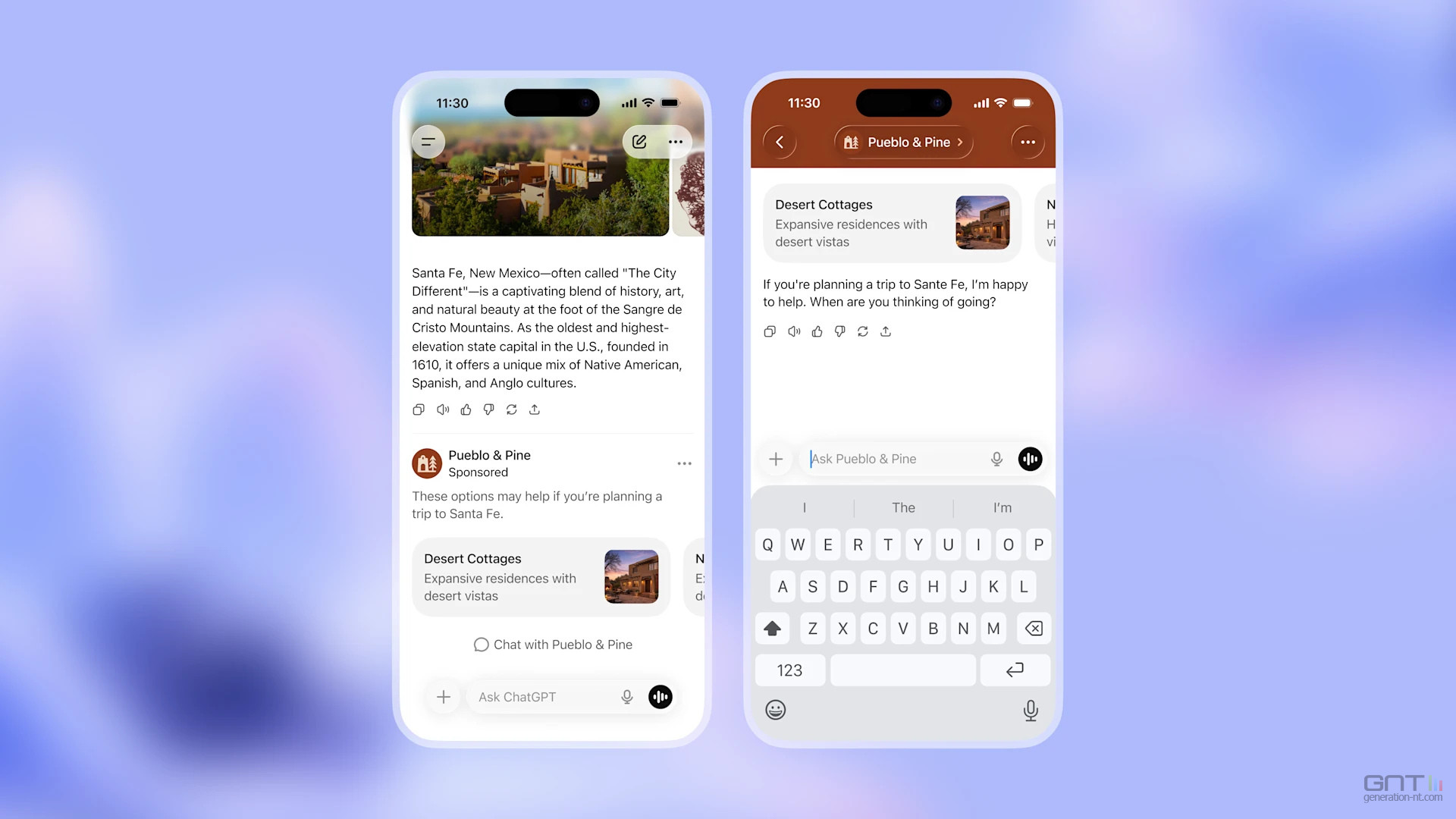

OpenAI a officialisé l'arrivée des publicités dans la version gratuite de ChatGPT et pour l'abonnement ChatGPT Go. Des écrans de présentation cherchent à rassurer les utilisateurs.