Looking for inconsistencies in the fine structure constant

New high-precision laser spectroscopy measurements on thorium-229 nuclei could shed more light on the fine structure constant, which determines the strength of the electromagnetic interaction, say physicists at TU Wien in Austria.

The electromagnetic interaction is one of the four known fundamental forces in nature, with the others being gravity and the strong and weak nuclear forces. Each of these fundamental forces has an interaction constant that describes its strength in comparison with the others. The fine structure constant, α, has a value of approximately 1/137. If it had any other value, charged particles would behave differently, chemical bonding would manifest in another way and light-matter interactions as we know them would not be the same.

“As the name ‘constant’ implies, we assume that these forces are universal and have the same values at all times and everywhere in the universe,” explains study leader Thorsten Schumm from the Institute of Atomic and Subatomic Physics at TU Wien. “However, many modern theories, especially those concerning the nature of dark matter, predict small and slow fluctuations in these constants. Demonstrating a non-constant fine-structure constant would shatter our current understanding of nature, but to do this, we need to be able to measure changes in this constant with extreme precision.”

With thorium spectroscopy, he says, we now have a very sensitive tool to search for such variations.

Nucleus becomes slightly more elliptic

The new work builds on a project that led, last year, to the worlds’s first nuclear clock, and is based on precisely determining how the thorium-229 (229Th) nucleus changes shape when one of its neutrons transitions from a ground state to a higher-energy state. “When excited, the 229Th nucleus becomes slightly more elliptic,” Schumm explains. “Although this shape change is small (at the 2% level), it dramatically shifts the contributions of the Coulomb interactions (the repulsion between protons in the nucleus) to the nuclear quantum states.”

The result is a change in the geometry of the 229Th nucleus’ electric field, to a degree that depends very sensitively on the value of the fine structure constant. By precisely observing this thorium transition, it is therefore possible to measure whether the fine-structure constant is actually a constant or whether it varies slightly.

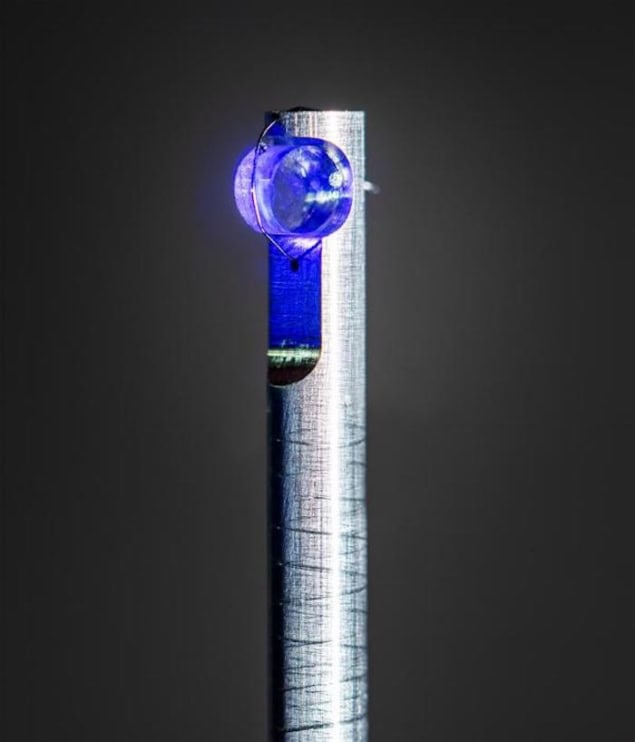

After making crystals of 229Th doped in a CaF2 matrix at TU Wien, the researchers performed the next phase of the experiment in a JILA laboratory at the University of Colorado, Boulder, US, firing ultrashort laser pulses at the crystals. While they did not measure any changes in the fine structure constant, they did succeed in determining how such changes, if they exist, would translate into modifications to the energy of the first nuclear excited state of 229Th.

“It turns out that this change is huge, a factor 6000 larger than in any atomic or molecular system, thanks to the high energy governing the processes inside nuclei,” Schumm says. “This means that we are by a factor of 6000 more sensitive to fine structure variations than previous measurements.”

Increasing the spectroscopic accuracy of the 229Th transition

Researchers in the field have debated the likelihood of such an “enhancement factor” for decades, and theoretical predictions of its value have varied between zero and 10 000. “Having confirmed such a high enhancement factor will now allow us to trigger a ‘hunt’ for the observation of fine structure variations using our approach,” Schumm says.

Andrea Caputo of CERN’s theoretical physics department, who was not involved in this work, calls the experimental result “truly remarkable”, as it probes nuclear structure with a precision that has never been achieved before. However, he adds that the theoretical framework is still lacking. “In a recent work published shortly before this work, my collaborators and I showed that the nuclear-clock enhancement factor K is still subject to substantial theoretical uncertainties,” Caputo says. “Much progress is therefore still required on the theory side to model the nuclear structure reliably.”

Schumm and colleagues are now working on increasing the spectroscopic accuracy of their 229Th transition measurement by another one to two orders of magnitude. “We will then start hunting for fluctuations in the transition energy,” he reveals, “tracing it over time and – through the Earth’s movement around the Sun – space.

The present work is detailed in Nature Communications.

The post Looking for inconsistencies in the fine structure constant appeared first on Physics World.