Cosmic time capsules: the search for pristine comets

In this episode of Physics World Stories, host Andrew Glester explores the fascinating hunt for pristine comets – icy bodies that preserve material from the solar system’s beginnings and even earlier. Unlike more familiar comets that repeatedly swing close to the Sun and transform, these frozen relics act as time capsules, offering unique insights into our cosmic history.

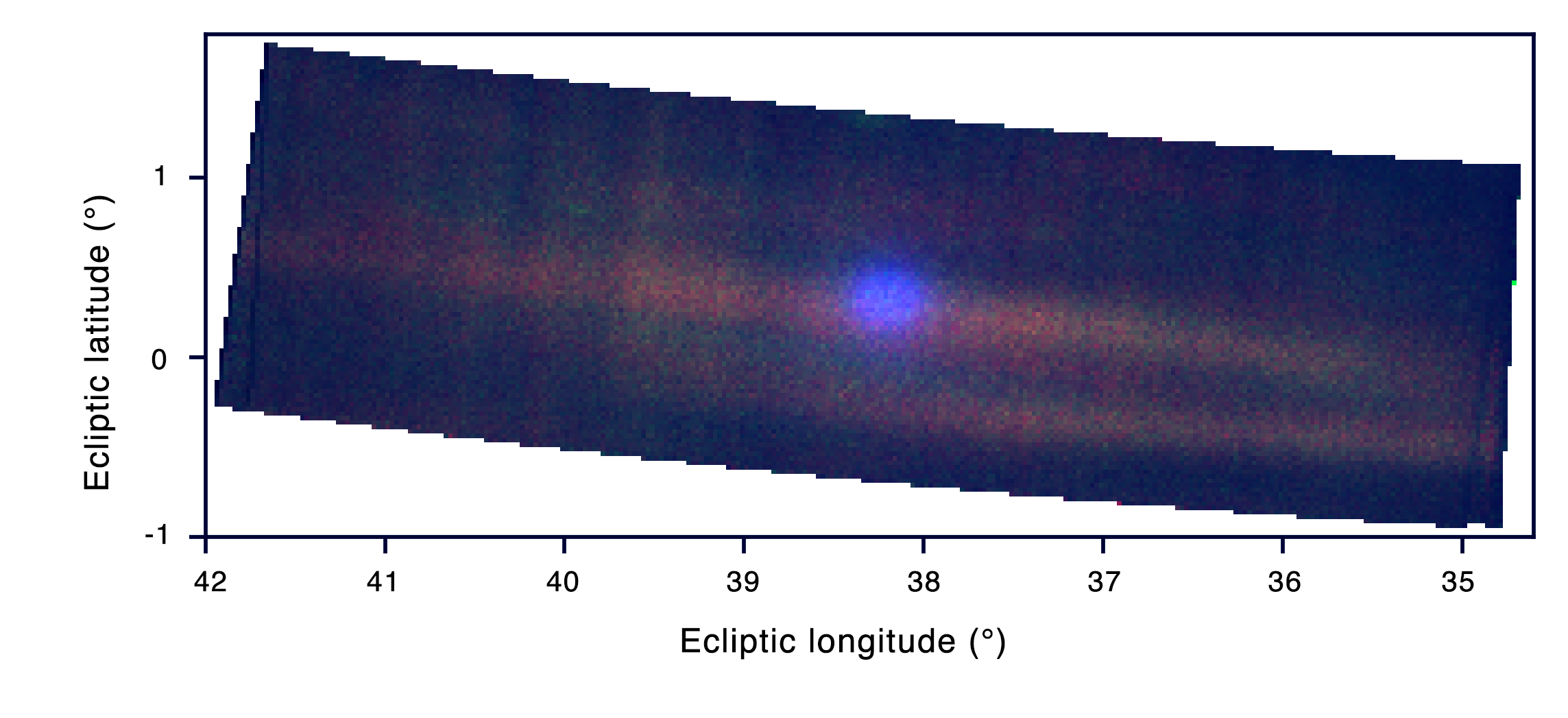

The first guest is Tracy Becker, deputy principal investigator for the Ultraviolet Spectrograph on NASA’s Europa Clipper mission. Becker describes how the Jupiter-bound spacecraft recently turned its gaze to 3I/ATLAS, an interstellar visitor that appeared last July. Mission scientists quickly reacted to this unique opportunity, which also enabled them to test the mission’s instruments before it arrives at the icy world of Europa.

Michael Küppers then introduces the upcoming Comet Interceptor mission, set for launch in 2029. This joint ESA–JAXA mission will “park” in space until a suitable comet arrives from the outer reaches of the solar system. They will deploy two probes to study it from multiple angles – offering a first-ever close look at material untouched since the solar system’s birth.

From interstellar wanderers to carefully orchestrated intercepts, this episode blends pioneering missions and cosmic detective work. Keep up to date with all the latest space and astronomy developments in the dedicated section of the Physics World website.

The post Cosmic time capsules: the search for pristine comets appeared first on Physics World.