Vue lecture

Post-Maduro, pressure builds on Mexico over Cuba’s new oil lifeline

The Fukushima towns frozen in time: nature has thrived since the nuclear disaster but what happens if humans return?

Fifteen years after a tsunami caused the Fukushima nuclear accident, only bears, raccoons and boar are seen on the streets. But the authorities and some locals want people to move back

Norio Kimura pauses to gaze through the dirt-flecked window of Kumamachi primary school in Fukushima. Inside, there are still textbooks lying on the desks, pencil cases are strewn across the floor; empty bento boxes that were never taken home.

Along the corridor, shoes line the route the children took when they fled, some still in their indoor plimsolls, as their town was rocked by a magnitude-9 earthquake on the afternoon of 11 March 2011 which went on to cause the world’s worst nuclear disaster since Chornobyl.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Kazuma Obara/The Guardian

© Photograph: Kazuma Obara/The Guardian

© Photograph: Kazuma Obara/The Guardian

First of its kind ‘high-density’ hydro system begins generating electricity in Devon

Project employs technology that can be used to store and release renewable energy using even gentle slopes

A hillside “battery” outside Plymouth in Devon has begun generating electricity using a first of a kind hydropower system embedded underground.

The pioneering technology means one of the oldest forms of energy storage, hydropower, can be used to store and release renewable energy using even gentle slopes rather than the steep dam walls and mountains that are usually required.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Taylor Keogh Communications/RheEnergise

© Photograph: Taylor Keogh Communications/RheEnergise

© Photograph: Taylor Keogh Communications/RheEnergise

Scotland-France ferry could relaunch amid £35bn Dunkirk regeneration plan

French port’s green energy push, evoking second world war spirit of resilience, is seen as a testing ground for reindustrialisation

A new cargo and passenger ferry service directly linking Scotland and France could launch later this year as the port of Dunkirk embarks on a €40bn (£35bn) regeneration programme it claims will mirror the second world war resilience for which it is famed.

The plans could include a new service between Rosyth in Fife and Dunkirk, eight years after the last freight ferries linked Scotland to mainland Europe, and 16 years after passenger services stopped.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Andrew Hayes/Alamy

© Photograph: Andrew Hayes/Alamy

© Photograph: Andrew Hayes/Alamy

How Does Climate Change Affect Winter Storms?

© Aristide Economopoulos for The New York Times

Number of people living in extreme heat to double by 2050 if 2C rise occurs, study finds

Scientists expect 41% of the projected global population to face the extremes, with ‘no part of the world’ immune

The number of people living with extreme heat will more than double by 2050 if global heating reaches 2C, according to a new study that shows how the energy demands for air conditioners and heating systems are expected to change across the world.

No region will escape the impact, say the authors. Although the tropics and southern hemisphere will be worst affected by rising heat, the countries in the north will also find it difficult to adapt because their built environments are primarily designed to deal with a cooler climate.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Francisco Seco/AP

© Photograph: Francisco Seco/AP

© Photograph: Francisco Seco/AP

American energy dominance gives us the power to fend off enemies and rescue Venezuela

UK among 10 countries to build 100GW wind power grid in North Sea

Energy secretary Ed Miliband says clean energy project is part of efforts to leave ‘the fossil fuel rollercoaster’

The UK and nine other European countries have agreed to build an offshore wind power grid in the North Sea in a landmark pact to turn the ageing oil basin into a “clean energy reservoir”.

The countries will build windfarms at sea that directly connect to multiple nations through high-voltage subsea cables, under plans that are expected to provide 100GW of offshore wind power, or enough electricity capacity to power 143m homes.

Continue reading...

© Photograph: Nature Picture Library/Alamy

© Photograph: Nature Picture Library/Alamy

© Photograph: Nature Picture Library/Alamy

NASA and DOE to collaborate on lunar nuclear reactor development

NASA and the Department of Energy have agreed to work together on development of nuclear reactors for the moon as industry awaits the release of a final call for proposals.

The post NASA and DOE to collaborate on lunar nuclear reactor development appeared first on SpaceNews.

Fuel cell catalyst requirements for heavy-duty vehicle applications

Heavy-duty vehicles (HDVs) powered by hydrogen-based proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells offer a cleaner alternative to diesel-powered internal combustion engines for decarbonizing long-haul transportation sectors. The development path of sub-components for HDV fuel-cell applications is guided by the total cost of ownership (TCO) analysis of the truck.

TCO analysis suggests that the cost of the hydrogen fuel consumed over the lifetime of the HDV is more dominant because trucks typically operate over very high mileages (~a million miles) than the fuel cell stack capital expense (CapEx). Commercial HDV applications consume more hydrogen and demand higher durability, meaning that TCO is largely related to the fuel-cell efficiency and durability of catalysts.

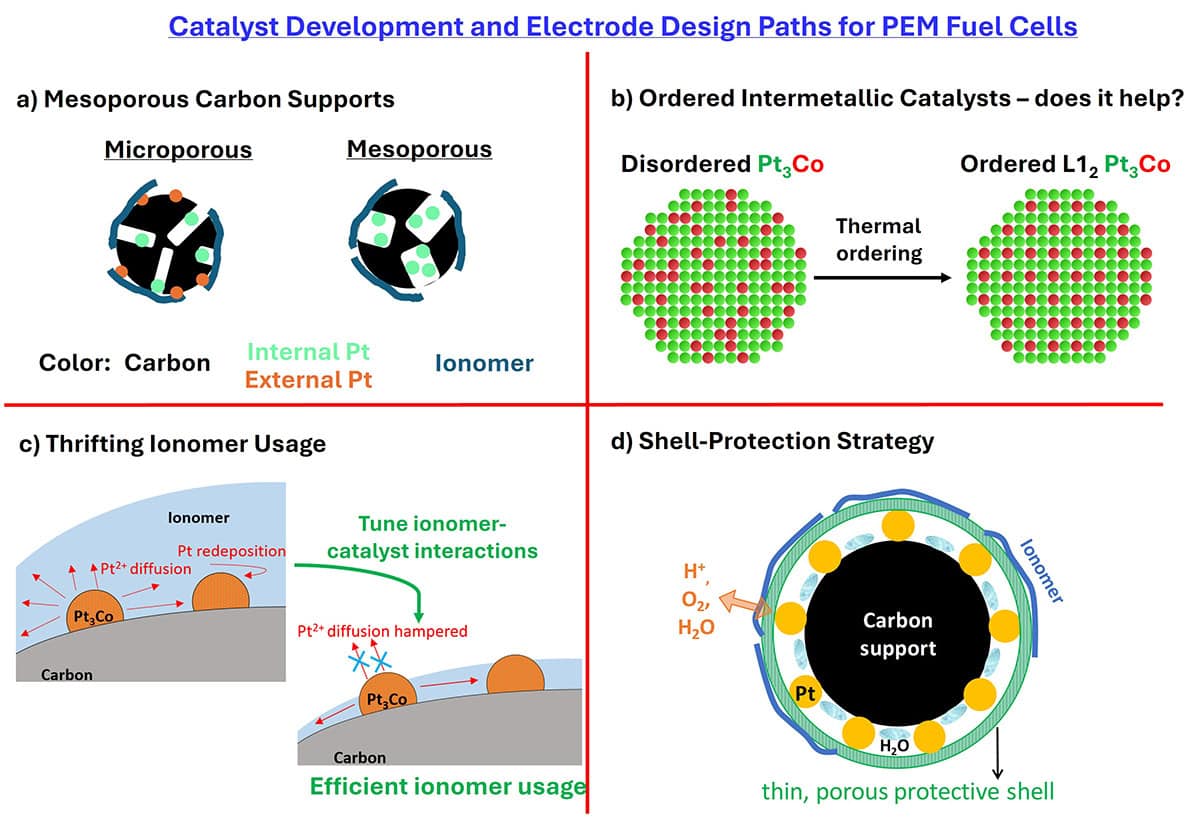

This article is written to bridge the gap between the industrial requirements and academic activity for advanced cathode catalysts with an emphasis on durability. From a materials perspective, the underlying nature of the carbon support, Pt-alloy crystal structure, stability of the alloying element, cathode ionomer volume fraction, and catalyst–ionomer interface play a critical role in improving performance and durability.

We provide our perspective on four major approaches, namely, mesoporous carbon supports, ordered PtCo intermetallic alloys, thrifting ionomer volume fraction, and shell-protection strategies that are currently being pursued. While each approach has its merits and demerits, their key developmental needs for future are highlighted.

Nagappan Ramaswamy joined the Department of Chemical Engineering at IIT Bombay as a faculty member in January 2025. He earned his PhD in 2011 from Northeastern University, Boston specialising in fuel cell electrocatalysis.

He then spent 13 years working in industrial R&D – two years at Nissan North American in Michigan USA focusing on lithium-ion batteries, followed by 11 years at General Motors in Michigan USA focusing on low-temperature fuel cells and electrolyser technologies. While at GM, he led two multi-million-dollar research projects funded by the US Department of Energy focused on the development of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells for automotive applications.

At IIT Bombay, his primary research interests include low-temperature electrochemical energy-conversion and storage devices such as fuel cells, electrolysers and redox-flow batteries involving materials development, stack design and diagnostics.

The post Fuel cell catalyst requirements for heavy-duty vehicle applications appeared first on Physics World.

CERN team solves decades-old mystery of light nuclei formation

When particle colliders smash particles into each other, the resulting debris cloud sometimes contains a puzzling ingredient: light atomic nuclei. Such nuclei have relatively low binding energies, and they would normally break down at temperatures far below those found in high-energy collisions. Somehow, though, their signature remains. This mystery has stumped physicists for decades, but researchers in the ALICE collaboration at CERN have now figured it out. Their experiments showed that light nuclei form via a process called resonance-decay formation – a result that could pave the way towards searches for physics beyond the Standard Model.

Baryon resonance

The ALICE team studied deuterons (a bound proton and neutron) and antideuterons (a bound antiproton and antineutron) that form in experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. Both deuterons and antideuterons are fragile, and their binding energies of 2.2 MeV would seemingly make it hard for them to form in collisions with energies that can exceed 100 MeV – 100 000 times hotter than the centre of the Sun.

The collaboration found that roughly 90% of the deuterons seen after such collisions form in a three-phase process. In the first phase, an initial collision creates a so-called baryon resonance, which is an excited state of a particle made of three quarks (such as a proton or neutron). This particle is called a Δ baryon and is highly unstable, so it rapidly decays into a pion and a nucleon (a proton or a neutron) during the second phase of the process. Then, in the third (and, crucially, much later) phase, the nucleon cools down to a point where its energy properties allow it to bind with another nucleon to form a deuteron.

Smoking gun

Measuring such a complex process is not easy, especially as everything happens on a length scale of femtometres (10-15 meter). To tease out the details, the collaboration performed precision measurements to correlate the momenta of the pions and deuterons. When they analysed the momentum difference between these particle pairs, they observed a peak in the data corresponding to the mass of the Δ baryon. This peak shows that the pion and the deuteron are kinematically linked because they share a common ancestor: the pion came from the same Δ decay that provided one of the deuteron’s nucleons.

Panos Christakoglou, a member of the ALICE collaboration based at the Netherlands’ Maastricht University, says the experiment is special because in contrast to most previous attempts, where results were interpreted in light of models or phenomenological assumptions, this technique is model-independent. He adds that the results of this study could be used to improve models of high energy proton-proton collisions in which light nuclei (and maybe hadrons more generally) are formed. Other possibilities include improving our interpretations of cosmic-ray studies that measure the fluxes of (anti)nuclei in the galaxy – a useful probe for astrophysical processes.

The hunt is on

Intriguingly, Christakoglou suggests that the team’s technique could also be used to search for indirect signs of dark matter. Many models predict that dark-matter candidates such as Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs) will decay or annihilate in processes that also produce Standard Model particles, including (anti)deuterons. “If for example one measures the flux of (anti)nuclei in cosmic rays being above the ‘Standard Model based’ astrophysical background, then this excess could be attributed to new physics which might be connected to dark matter,” Christakoglou tells Physics World.

Michael Kachelriess, a physicist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, Norway, who was not involved in this research, says the debate over the correct formation mechanism for light nuclei (and antinuclei) has divided particle physicists for a long time. In his view, the data collected by the ALICE collaboration decisively resolves this debate by showing that light nuclei form in the late stages of a collision via the coalescence of nucleons. Kachelriess calls this a “great achievement” in itself, and adds that similar approaches could make it possible to address other questions, such as whether thermal plasmas form in proton-proton collisions as well as in collisions between heavy ions.

The post CERN team solves decades-old mystery of light nuclei formation appeared first on Physics World.

Transparent and insulating aerogel could boost energy efficiency of windows

An aerogel material that is more than 99% transparent to light and is an excellent thermal insulator has been developed by Ivan Smalyukh and colleagues at the University of Colorado Boulder in the US. Called MOCHI, the material can be manufactured in large slabs and could herald a major advance in energy-efficient windows.

While the insulating properties of building materials have steadily improved over the past decades, windows have consistently lagged behind. The problem is that current materials used in windows – mostly glass – have an inherent trade-off between insulating ability and optical transparency. This is addressed to some extent by using two or three layers of glass in double- and triple-glazed windows. However, windows remain the largest source of heat loss from most buildings.

A solution to the window problem could lie with aerogels in which the liquid component of a regular gel is replaced with air. This creates solid materials with networks of pores that make aerogels the lightest solid materials ever produced. If the solid component is a poor conductor of heat, then the aerogel will be an extremely good thermal insulator.

“Conventional aerogels, like the silica and cellulose based ones, are common candidates for transparent, thermally insulating materials,” Smalyukh explains. “However, their visible-range optical transparency is intrinsically limited by the scattering induced by their polydisperse pores – which can range from nanometres to micrometres in scale.”

Hazy appearance

While this problem can be overcome fairly easily in thin aerogel films, creating appropriately-sized pores on the scale of practical windows has so far proven much more difficult, leading to a hazy, translucent appearance.

Now, Smalyukh’s team has developed a new fabrication technique involving a removable template. Their approach hinges on the tendency of surfactant molecules called CPCL to self-assemble in water. Under carefully controlled conditions, the molecules spontaneously form networks of cylindrical tubes, called micelles. Once assembled, the aerogel precursor – a silicone material called polysiloxane – condenses around the micelles, freezing their structure in place.

“The ensuing networks of micelle-templated polysiloxane tubes could be then preserved upon the removal of surfactant, and replacing the fluid solvent with air,” Smalyukh describes. The end result was a consistent mesoporous structure, with pores ranging from 2–50 nm in diameter. This is too small to scatter visible light, but large enough to interfere with heat transport.

As a result, the mesoporous, optically clear heat insulator (MOCHI) maintains its transparency even when fabricated in slabs over 3 cm thick and a square metre in area. This suggests that it could be used to create practical windows.

High thermal performance

“We demonstrated thermal conductivity lower than that of still air, as well as an average light transmission above 99%,” Smalyukh says. “Therefore, MOCHI glass units can provide a similar rate of heat transfer to high-performing building roofs and walls, with thicknesses comparable to double pane windows.”

If rolled out on commercial scales, this could lead to entirely new ways to manage interior heating and cooling. According to the team’s calculations, a building retrofitted with MOCHI windows could boost its energy efficiency from around 6% (a typical value in current buildings) to over 30%, while reducing the heat energy passing through by around 50%.

With its ability to admit light while blocking heat transport, the researchers suggest that MOCHI could unlock entirely new functionalities for conventional windows. “Such transparent insulation also allows for efficient harnessing of thermal energy from unconcentrated solar radiation in different climate zones, promising the use of parts of opaque building envelopes as solar thermal energy generating panels,” Smalyukh adds.

The new material is described in Science.

The post Transparent and insulating aerogel could boost energy efficiency of windows appeared first on Physics World.

So you want to install a wind turbine? Here’s what you need to know

As a physicist in industry, I spend my days developing new types of photovoltaic (PV) panels. But I’m also keen to do something for the transition to green energy outside work, which is why I recently installed two PV panels on the balcony of my flat in Munich. Fitting them was great fun – and I can now enjoy sunny days even more knowing that each panel is generating electricity.

However, the panels, which each have a peak power of 440 W, don’t cover all my electricity needs, which prompted me to take an interest in a plan to build six wind turbines in a forest near me on the outskirts of Munich. Curious about the project, I particularly wanted to find out when the turbines will start generating electricity for the grid. So when I heard that a weekend cycle tour of the site was being organized to showcase it to local residents, I grabbed my bike and joined in.

As we cycle, I discover that the project – located in Forstenrieder Park – is the joint effort of four local councils and two “citizen-energy” groups, who’ve worked together for the last five years to plan and start building the six turbines. Each tower will be 166 m high and the rotor blades will be 80 m long, with the plan being for them to start operating in 2027.

I’ve never thought of Munich as a particularly windy city, but at the height at which the blades operate, there’s always a steady, reliable flow of wind

I’ve never thought of Munich as a particularly windy city. But tour leader Dieter Maier, who’s a climate adviser to Neuried council, explains that at the height at which the blades operate, there’s always a steady, reliable flow of wind. In fact, each turbine has a designed power output of 6.5 MW and will deliver a total of 10 GWh in energy over the course of a year.

Practical questions

Cycling around, I’m excited to think that a single turbine could end up providing the entire electricity demand for Neuried. But installing wind turbines involves much more than just the technicalities of generating electricity. How do you connect the turbines to the grid? How do you ensure planes don’t fly into the turbines? What about wildlife conservation and biodiversity?

At one point of our tour, we cycle round a 90-degree bend in the forest and I wonder how a huge, 80 m-long blade will be transported round that kind of tight angle? Trees will almost certainly have to be felled to get the blade in place, which sounds questionable for a supposedly green project. Fortunately, project leaders have been working with the local forest manager and conservationists, finding ways to help improve the local biodiversity despite the loss of trees.

As a representative of BUND (one of Germany’s biggest conservation charities) explains on the tour, a natural, or “unmanaged”, forest consists of a mix of areas with a higher or lower density of trees. But Forstenrieder Park has been a managed forest for well over a century and is mostly thick with trees. Clearing trees for the turbines will therefore allow conservationists to grow more of the bushes and plants that currently struggle to find space to flourish.

To avoid endangering birds and bats native to this forest, meanwhile, the turbines will be turned off when the animals are most active, which coincidentally corresponds to low wind periods in Munich. Insurance costs have to be factored in too. Thankfully, it’s quite unlikely that a turbine will burn down or get ice all over its blades, which means liability insurance costs are low. But vandalism is an ever-present worry.

In fact, at the end of our bike tour, we’re taken to a local wind turbine that is already up and running about 13 km further south of Forstenrieder Park. This turbine, I’m disappointed to discover, was vandalized back in 2024, which led to it being fenced off and video surveillance cameras being installed.

But for all the difficulties, I’m excited by the prospect of the wind turbines supporting the local energy needs. I can’t wait for the day when I’m on my balcony, solar panels at my side, sipping a cup of tea made with water boiled by electricity generated by the rotor blades I can see turning round and round on the horizon.

The post So you want to install a wind turbine? Here’s what you need to know appeared first on Physics World.

Galactic gamma rays could point to dark matter

Gamma rays emitted from the halo of the Milky Way could be produced by hypothetical dark-matter particles. That is the conclusion of an astronomer in Japan who has analysed data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The energy spectrum of the emission is what would be expected from the annihilation of particles called WIMPs. If this can be verified, it would mark the first observation of dark matter via electromagnetic radiation.

Since the 1930s astronomers have known that there is something odd about galaxies, galaxy clusters and larger structures in the universe. The problem is that there is not nearly enough visible matter in these objects to explain their dynamics and structure. A rotating galaxy, for example, should be flinging out its stars because it does not have enough self-gravitation to hold itself together.

Today, the most popular solution to this conundrum is the existence of a hypothetical substance called dark matter. Dark-matter particles would have mass and interact with each other and normal matter via the gravitational force, gluing rotating galaxies together. However, the fact that we have never observed dark matter directly means that the particles must rarely, if ever, interact via the other three forces.

Annihilating WIMPs

The weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP) is a dark-matter candidate that interacts via the weak nuclear force (or a similarly weak force). As a result of this interaction, pairs of WIMPs are expected to occasionally annihilate to create high-energy gamma rays and other particles. If this is true, dense areas of the universe such as galaxies should be sources of these gamma rays.

Now, Tomonori Totani of the University of Tokyo has analysed data from the Fermi telescope and identified an excess of gamma rays emanating from the halo of the Milky Way. What is more, Totani’s analysis suggests that the energy spectrum of the excess radiation (from about 10−100 GeV) is consistent with hypothetical WIMP annihilation processes.

“If this is correct, to the extent of my knowledge, it would mark the first time humanity has ‘seen’ dark matter,” says Totani. “This signifies a major development in astronomy and physics,” he adds.

While Totani is confident of his analysis, his conclusion must be verified independently. Furthermore, work will be needed to rule out conventional astrophysical sources of the excess radiation.

Catherine Heymans, who is Astronomer Royal for Scotland told Physics World, “I think it’s a really nice piece of work, and exactly what should be happening with the Fermi data”. The research is described in Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. Heymans describes Totani’s paper as “well written and thorough”.

The post Galactic gamma rays could point to dark matter appeared first on Physics World.

Heat engine captures energy as Earth cools at night

A new heat engine driven by the temperature difference between Earth’s surface and outer space has been developed by Tristan Deppe and Jeremy Munday at the University of California Davis. In an outdoor trial, the duo showed how their engine could offer a reliable source of renewable energy at night.

While solar cells do a great job of converting the Sun’s energy into electricity, they have one major drawback, as Munday explains: “Lack of power generation at night means that we either need storage, which is expensive, or other forms of energy, which often come from fossil fuel sources.”

One solution is to exploit the fact that the Earth’s surface absorbs heat from the Sun during the day and then radiates some of that energy into space at night. While space has a temperature of around −270° C, the average temperature of Earth’s surface is a balmy 15° C. Together, these two heat reservoirs provide the essential ingredients of a heat engine, which is a device that extracts mechanical work as thermal energy flows from a heat source to a heat sink.

Coupling to space

“At first glance, these two entities appear too far apart to be connected through an engine. However, by radiatively coupling one side of the engine to space, we can achieve the needed temperature difference to drive the engine,” Munday explains.

For the concept to work, the engine must radiate the energy it extracts from the Earth within the atmospheric transparency window. This is a narrow band of infrared wavelengths that pass directly into outer space without being absorbed by the atmosphere.

To demonstrate this concept, Deppe and Munday created a Stirling engine, which operates through the cyclical expansion and contraction of an enclosed gas as it moves between hot and cold ends. In their setup, the ends were aligned vertically, with a pair of plates connecting each end to the corresponding heat reservoir.

For the hot end, an aluminium mount was pressed into soil, transferring the Earth’s ambient heat to the engine’s bottom plate. At the cold end, the researchers attached a black-coated plate that emitted an upward stream of infrared radiation within the transparency window.

Outdoor experiments

In a series of outdoor experiments performed throughout the year, this setup maintained a temperature difference greater than 10° C between the two plates during most months. This was enough to extract more than 400 mW per square metre of mechanical power throughout the night.

“We were able to generate enough power to run a mechanical fan, which could be used for air circulation in greenhouses or residential buildings,” Munday describes. “We also configured the device to produce both mechanical and electrical power simultaneously, which adds to the flexibility of its operation.”

With this promising early demonstration, the researchers now predict that future improvements could enable the system to extract as much as 6 W per square metre under the same conditions. If rolled out commercially, the heat engine could help reduce the reliance of solar power on night-time energy storage – potentially opening a new route to cutting carbon emissions.

The research has described in Science Advances.

The post Heat engine captures energy as Earth cools at night appeared first on Physics World.

Reversible degradation phenomenon in PEMWE cells

In proton exchange membrane water electrolysis (PEMWE) systems, voltage cycles dropping below a threshold are associated with reversible performance improvements, which remain poorly understood despite being documented in literature. The distinction between reversible and irreversible performance changes is crucial for accurate degradation assessments. One approach in literature to explain this behaviour is the oxidation and reduction of iridium. Iridium-based electrocatalyst activity and stability in PEMWE hinge on their oxidation state, influenced by the applied voltage. Yet, full-cell PEMWE dynamic performance remains under-explored, with a focus typically on stability rather than activity. This study systematically investigates reversible performance behaviour in PEMWE cells using Ir-black as an anodic catalyst. Results reveal a recovery effect when the low voltage level drops below 1.5 V, with further enhancements observed as the voltage decreases, even with a short holding time of 0.1 s. This reversible recovery is primarily driven by improved anode reaction kinetics, likely due to changing iridium oxidation states, and is supported by alignment between the experimental data and a dynamic model that links iridium oxidation/reduction processes to performance metrics. This model allows distinguishing between reversible and irreversible effects and enables the derivation of optimized operation schemes utilizing the recovery effect.

Tobias Krenz is a simulation and modelling engineer at Siemens Energy in the Transformation of Industry business area focusing on reducing energy consumption and carbon-dioxide emissions in industrial processes. He completed his PhD from Liebniz University Hannover in February 2025. He earned a degree from Berlin University of Applied Sciences in 2017 and a MSc from Technische Universität Darmstadt in 2020.

Alexander Rex is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Electric Power Systems at Leibniz University Hannover. He holds a degree in mechanical engineering from Technische Universität Braunschweig, an MEng from Tongji University, and an MSc from Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). He was a visiting scholar at Berkeley Lab from 2024 to 2025.

The post Reversible degradation phenomenon in PEMWE cells appeared first on Physics World.

Flattened halo of dark matter could explain high-energy ‘glow’ at Milky Way’s heart

Astronomers have long puzzled over the cause of a mysterious “glow” of very high energy gamma radiation emanating from the centre of our galaxy. One possibility is that dark matter – the unknown substance thought to make up more than 25% of the universe’s mass – might be involved. Now, a team led by researchers at Germany’s Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) says that a flattened rather than spherical distribution of dark matter could account for the glow’s properties, bringing us a step closer to solving the mystery.

Dark matter is believed to be responsible for holding galaxies together. However, since it does not interact with light or other electromagnetic radiation, it can only be detected through its gravitational effects. Hence, while astrophysical and cosmological evidence has confirmed its presence, its true nature remains one of the greatest mysteries in modern physics.

“It’s extremely consequential and we’re desperately thinking all the time of ideas as to how we could detect it,” says Joseph Silk, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University in the US and the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris and Sorbonne University in France who co-led this research together with the AIP’s Moorits Mihkel Muru. “Gamma rays, and specifically the excess light we’re observing at the centre of our galaxy, could be our first clue.”

Models might be too simple

The problem, Muru explains, is that the way scientists have usually modelled dark matter to account for the excess gamma-ray radiation in astronomical observations was highly simplified. “This, of course, made the calculations easier, but simplifications always fuzzy the details,” he says. “We showed that in this case, the details are important: we can’t model dark matter as a perfectly symmetrical cloud and instead have to take into account the asymmetry of the cloud.”

Muru adds that the team’s findings, which are detailed in Phys. Rev. Lett., provide a boost to the “dark matter annihilation” explanation of the excess radiation. According to the standard model of cosmology, all galaxies – including our own Milky Way – are nested inside huge haloes of dark matter. The density of this dark matter is highest at the centre, and while it primarily interacts through gravity, some models suggest that it could be made of massive, neutral elementary particles that are their own antimatter counterparts. In these dense regions, therefore, such dark matter species could be mutually annihilating, producing substantial amounts of radiation.

Pierre Salati, an emeritus professor at the Université Savoie Mont Blanc, France, who was not involved in this work, says that in these models, annihilation plays a crucial role in generating a dark matter component with an abundance that agrees with cosmological observations. “Big Bang nucleosynthesis sets stringent bounds on these models as a result of the overall concordance between the predicted elemental abundances and measurements, although most models do survive,” Salati says. “One of the most exciting aspects of such explanations is that dark matter species might be detected through the rare antimatter particles – antiprotons, positrons and anti-deuterons – that they produce as they currently annihilate inside galactic halos.”

Silvia Manconi of the Laboratoire de Physique Théorique et Hautes Energies (LPTHE), France, who was also not involved in the study, describes it as “interesting and stimulating”. However, she cautions that – as is often the case in science – reality is probably more complex than even advanced simulations can capture. “This is not the first time that galaxy simulations have been used to study the implications of the excess and found non-spherical shapes,” she says, though she adds that the simulations in the new work offer “significant improvements” in terms of their spatial resolution.

Manconi also notes that the study does not demonstrate how the proposed distribution of dark matter would appear in data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope’s Large Area Telescope (LAT), or how it would differ quantitatively from observations of a distribution of old stars. Forthcoming observations with radio telescopes such as MeerKat and FAST, she adds, may soon identify pulsars in this region of the galaxy, shedding further light on other possible contributions to the excess of gamma rays.

New telescopes could help settle the question

Muru acknowledges that better modelling and observations are still needed to rule out other possible hypotheses. “Studying dark matter is very difficult, because it doesn’t emit or block light, and despite decades of searching, no experiment has yet detected dark matter particles directly,” he tells Physics World. “A confirmation that this observed excess radiation is caused by dark matter annihilation through gamma rays would be a big leap forward.”

New gamma-ray telescopes with higher resolution, such as the Cherenkov Telescope Array, could help settle this question, he says. If these telescopes, which are currently under construction, fail to find star-like sources for the glow and only detect diffuse radiation, that would strengthen the alternative dark matter annihilation explanation.

Muru adds that a “smoking gun” for dark matter would be a signal that matches current theoretical predictions precisely. In the meantime, he and his colleagues plan to work on predicting where dark matter should be found in several of the dwarf galaxies that circle the Milky Way.

“It’s possible we will see the new data and confirm one theory over the other,” Silk says. “Or maybe we’ll find nothing, in which case it’ll be an even greater mystery to resolve.”

The post Flattened halo of dark matter could explain high-energy ‘glow’ at Milky Way’s heart appeared first on Physics World.