Quantum-scale thermodynamics offers a tighter definition of entropy

A new, microscopic formulation of the second law of thermodynamics for coherently driven quantum systems has been proposed by researchers in Switzerland and Germany. The researchers applied their formulation to several canonical quantum systems, such as a three-level maser. They believe the result provides a tighter definition of entropy in such systems, and could form a basis for further exploration.

In any physical process, the first law of thermodynamics says that the total energy must always be conserved, with some converted to useful work and the remainder dissipated as heat. The second law of thermodynamics says that, in any allowed process, the total amount of heat (the entropy) must always increase.

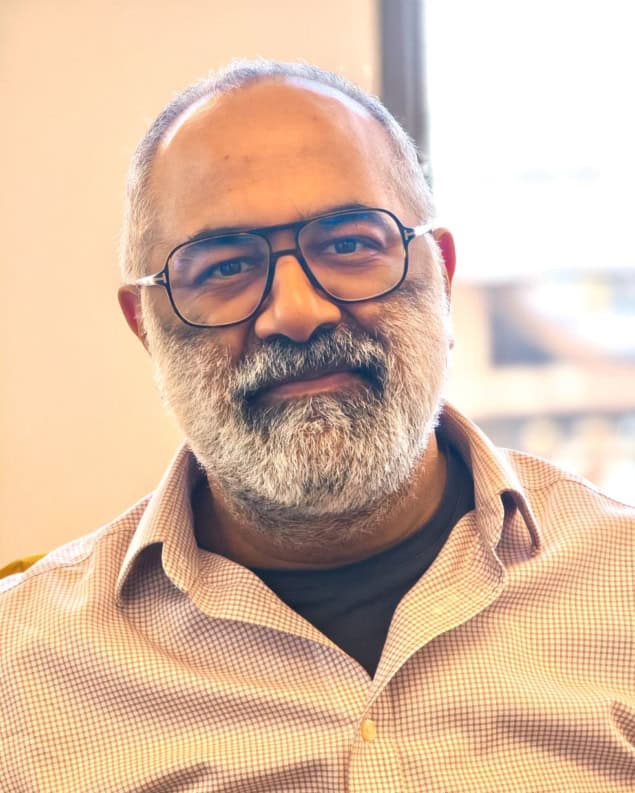

“I like to think of work being mediated by degrees of freedom that we control and heat being mediated by degrees of freedom that we cannot control,” explains theoretical physicist Patrick Potts of the University of Basel in Switzerland. “In the macroscopic scenario, for example, work would be performed by some piston – we can move it.” The heat, meanwhile, goes into modes such as phonons generated by friction.

Murky at small scales

This distinction, however, becomes murky at small scales: “Once you go microscopic everything’s microscopic, so it becomes much more difficult to say ‘what is it that that you control – where is the work mediated – and what is it that you cannot control?’,” says Potts.

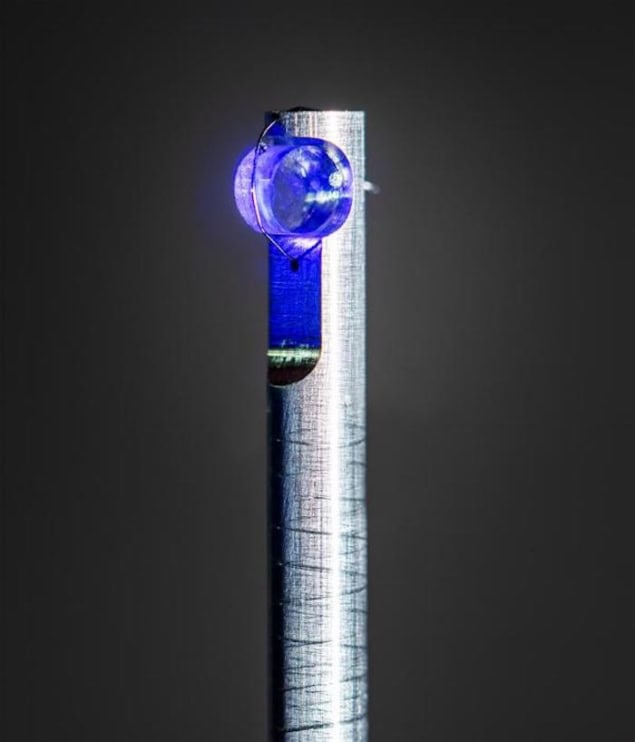

Potts and colleagues in Basel and at RWTH Aachen University in Germany examined the case of optical cavities driven by laser light, systems that can do work: “If you think of a laser as being able to promote a system from a ground state to an excited state, that’s very important to what’s being done in quantum computers, for example,” says Potts. “If you rotate a qubit, you’re doing exactly that.”

The light interacts with the cavity and makes an arbitrary number of bounces before leaking out. This emergent light is traditionally treated as heat in quantum simulations. However, it can still be partially coherent – if the cavity is empty, it can be just as coherent as the incoming light and can do just as much work.

In 2020, quantum optician Alexia Auffèves of Université Grenoble Alpes in France and colleagues noted that the coherent component of the light exiting a cavity could potentially do work. In the new study, the researchers embedded this in a consistent thermodynamic framework. They studied several examples and formulated physically consistent laws of thermodynamics.

In particular, they looked at the three-level maser, which is a canonical example of a quantum heat engine. However, it has generally been modelled semi-classically by assuming that the cavity contains a macroscopic electromagnetic field.

Work vanishes

“The old description will tell you that you put energy into this macroscopic field and that is work,” says Potts, “But once you describe the cavity quantum mechanically using the old framework then – poof! – the work is gone…Putting energy into the light field is no longer considered work, and whatever leaves the cavity is considered heat.”

The researchers new thermodynamic treatment allows them to treat the cavity quantum mechanically and to parametrize the minimum degree of entropy in the radiation that emerges – how much radiation must be converted to uncontrolled degrees of freedom that can do no useful work and how much can remain coherent.

The researchers are now applying their formalism to study thermodynamic uncertainty relations as an extension of the traditional second law of thermodynamics. “It’s actually a trade-off between three things – not just efficiency and power, but fluctuations also play a role,” says Potts. “So the more fluctuations you allow for, the higher you can get the efficiency and the power at the same time. These three things are very interesting to look at with this new formalism because these thermodynamic uncertainty relations hold for classical systems, but not for quantum systems.”

“This [work] fits very well into a question that has been heavily discussed for a long time in the quantum thermodynamics community, which is how to properly define work and how to properly define useful resources,” says quantum theorist Federico Cerisola of the UK’s University of Exeter. “In particular, they very convincingly argue that, in the particular family of experiments they’re describing, there are resources that have been ignored in the past when using more standard approaches that can still be used for something useful.”

Cerisola says that, in his view, the logical next step is to propose a system – ideally one that can be implemented experimentally – in which radiation that would traditionally have been considered waste actually does useful work.

The research is described in Physical Review Letters.

The post Quantum-scale thermodynamics offers a tighter definition of entropy appeared first on Physics World.