Hidden Underwater Volcanoes May Explain Half of Earth’s Triassic Extinctions

Upcoming tabletop exercise will examine response to weapons of mass destruction in orbit

The post U.S. Space Command to bring commercial firms into classified wargame on nuclear threats in space appeared first on SpaceNews.

Gen. Stephen Whiting: A space becomes a contested military domain, the Pentagon needs not just rockets but also a sustainment and mobility infrastructure to support satellites

The post Space Command’s case for orbital logistics: Why the Pentagon is being urged to think beyond launch appeared first on SpaceNews.

The Space Futures Centre a global independent center established in partnership with the World Economic Forum and the Saudi Space Agency to support the growth of the global space economy […]

The post Space Futures Centre, World Economic Forum Launch Space Debris Insights Report appeared first on SpaceNews.

OQ Technology is preparing to deploy a small satellite to test using C-band to connect smartphones from LEO, joining SpaceX in a push to repurpose part of the spectrum for direct-to-device services.

The post OQ Technology plots smartphone test amid SpaceX’s C-band D2D push appeared first on SpaceNews.

China appears set to accelerate its launch rate this year while also conducting tests key to its crewed lunar ambitions and launching major missions.

The post China set for crewed lunar tests, record launches, moon mission and reusable rockets in 2026 appeared first on SpaceNews.

For more than a decade, the Earth observation industry has insisted that commercial adoption is just around the corner. Yet adoption outside defense remains limited, uneven, and difficult to sustain. The question is no longer whether EO is valuable, but whether the industry is delivering it in a form commercial users can actually use. The […]

The post Earth observation’s adoption gap is a supply design problem appeared first on SpaceNews.

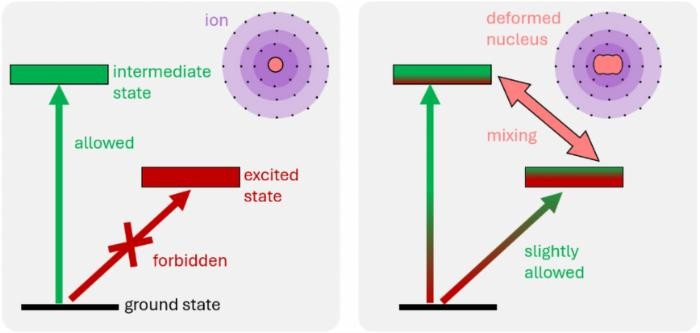

An atomic transition in ytterbium-173 could be used to create an optical multi-ion clock that is both precise and stable. That is the conclusion of researchers in Germany and Thailand who have characterized a clock transition that is enhanced by the non-spherical shape of the ytterbium-173 nucleus. As well as applications in timekeeping, the transition could be used in quantum computing. Furthermore, the interplay between atomic and nuclear effects in the transition could provide insights into the physics of deformed nuclei.

The ticking of an atomic clock is defined by the frequency of the electromagnetic radiation that is absorbed and emitted by a specific transition between atomic energy levels. These clocks play crucial roles in technologies that require precision timing – such as global navigation satellite systems and communications networks. Currently, the international definition of the second is given by the frequency of caesium-based clocks, which deliver microwave time signals.

Today’s best clocks, however, work at higher optical frequencies and are therefore much more precise than microwave clocks. Indeed, at some point in the future metrologists will redefine the second in terms of an optical transition – but the international metrology community has yet to decide which transition will be used.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of optical clock. One uses an ensemble of atoms that are trapped and cooled to ultralow temperatures using lasers; the other involves a single atomic ion (or a few ions) held in an electromagnetic trap. Clocks that use one ion are extremely precise, but lack stability; whereas clocks that use many atoms are very stable, but sacrifice precision.

As a result, some physicists are developing clocks that use multiple ions with the aim of creating a clock that optimizes precision and stability.

Now, researchers at PTB and NIMT (the national metrology institutes of Germany and Thailand respectively) have characterized a clock transition in ions of ytterbium-173, and have shown that the transition could be used to create a multi-ion clock.

“This isotope has a particularly interesting transition,” explains PTB’s Tanja Mehlstäubler – who is a pioneer in the development of multi-ion clocks.

The ytterbium-173 nucleus is highly deformed with a shape that resembles a rugby ball. This deformation affects the electronic properties of the ion, which should make it much easier to use a laser to excite a specific transition that would be very useful for creating a multi-ion clock.

This clock transition can also be excited in ytterbium-171 and has already been used to create a single-ion clock. However, excitation in a ytterbium-171 clock requires an intense laser pulse, which creates a strong electric field that shifts the clock frequency (called the AC Stark effect). This is a particular problem for multi-ion clocks because the intensity of the laser (and hence the clock frequency) can vary across the region in which the ions are trapped.

To show that a much lower laser intensity can be used to excite the clock transition in ytterbium-173, the team studied a “Coulomb crystal” in which three ions were trapped in a line and separated by about 10 micron. They illuminated the ions with laser light that was not uniform in intensity across the crystal. They were able to excite the transition at a relatively low laser intensity, which resulted in very small AC Stark shifts between the frequencies of the three ions.

According to the team, this means that as many as 100 trapped ytterbium-173 ions could be used to create a clock that could be used as a time standard; to redefine the second; and also to make very precise measurements of the Earth’s gravitational field.

As well as being useful for creating an optical ion clock, this multi-ion capability could also be exploited to create quantum-computing architectures based on multiple trapped ions. And because the observed effect is a result of the shape of the ytterbium-173 nucleus, further studies could provide insights into nuclear physics.

The research is described in Physical Review Letters.

The post Ion-clock transition could benefit quantum computing and nuclear physics appeared first on Physics World.

The Federal Aviation Administration office that regulates commercial spaceflight expects continued growth in launches, despite industry concerns about whether the office can keep pace.

The post FAA projects continuing growth in commercial space transportation appeared first on SpaceNews.

Most researchers know the disappointment of submitting an abstract to give a conference lecture, only to find that it has been accepted as a poster presentation instead. If this has been your experience, I’m here to tell you that you need to rethink the value of a good poster.

For years, I pestered my university to erect a notice board outside my office so that I could showcase my group’s recent research posters. Each time, for reasons of cost, my request was unsuccessful. At the same time, I would see similar boards placed outside the offices of more senior and better-funded researchers in my university. I voiced my frustrations to a mentor whose advice was, “It’s better to seek forgiveness than permission.” So, since I couldn’t afford to buy a notice board, I simply used drawing pins to mount some unauthorized posters on the wall beside my office door.

Some weeks later, I rounded the corner to my office corridor to find the head porter standing with a group of visitors gathered around my posters. He was telling them all about my research using solar energy to disinfect contaminated drinking water in disadvantaged communities in Sub-Saharan Africa. Unintentionally, my illegal posters had been subsumed into the head porter’s official tour that he frequently gave to visitors.

The group moved on but one man stayed behind, examining the poster very closely. I asked him if he had any questions. “No, thanks,” he said, “I’m not actually with the tour, I’m just waiting to visit someone further up the corridor and they’re not ready for me yet. Your research in Africa is very interesting.” We chatted for a while about the challenges of working in resource-poor environments. He seemed quite knowledgeable on the topic but soon left for his meeting.

A few days later while clearing my e-mail junk folder I spotted an e-mail from an Asian “philanthropist” offering me €20,000 towards my research. To collect the money, all I had to do was send him my bank account details. I paused for a moment to admire the novelty and elegance of this new e-mail scam before deleting it. Two days later I received a second e-mail from the same source asking why I hadn’t responded to their first generous offer. While admiring their persistence, I resisted the urge to respond by asking them to stop wasting their time and mine, and instead just deleted it.

So, you can imagine my surprise when the following Monday morning I received a phone call from the university deputy vice-chancellor inviting me to pop up for a quick chat. On arrival, he wasted no time before asking why I had been so foolish as to ignore repeated offers of research funding from one of the college’s most generous benefactors. And that is how I learned that those e-mails from the Asian philanthropist weren’t bogus.

The gentleman that I’d chatted with outside my office was indeed a wealthy philanthropic funder who had been visiting our university. Having retrieved the e-mails from my deleted items folder, I re-engaged with him and subsequently received €20,000 to install 10,000-litre harvested-rainwater tanks in as many primary schools in rural Uganda as the money would stretch to.

About six months later, I presented the benefactor with a full report accounting for the funding expenditure, replete with photos of harvested-rainwater tanks installed in 10 primary schools, with their very happy new owners standing in the foreground. Since you miss 100% of the chances you don’t take, I decided I should push my luck and added a “wish list” of other research items that the philanthropist might consider funding.

The list started small and grew steadily ambitious. I asked for funds for more tanks in other schools, a travel bursary, PhD registration fees, student stipends and so on. All told, the list came to a total of several hundred thousand euros, but I emphasized that they had been very generous so I would be delighted to receive funding for any one of the listed items and, even if nothing was funded, I was still very grateful for everything he had already done. The following week my generous patron deposited a six-figure-euro sum into my university research account with instructions that it be used as I saw fit for my research purposes, “under the supervision of your university finance office”.

In my career I have co-ordinated several large-budget, multi-partner, interdisciplinary, international research projects. In each case, that money was hard-earned, needing at least six months and many sleepless nights to prepare the grant submission. It still amuses me that I garnered such a large sum on the back of one research poster, one 10-minute chat and fewer than six e-mails.

So, if you have learned nothing else from this story, please don’t underestimate the power of a strategically placed and impactful poster describing your research. You never know with whom it may resonate and down which road it might lead you.

The post The power of a poster appeared first on Physics World.

IRVINE, CA – January 28, 2026 – Terran Orbital proudly announces the Mitsubishi Electric LEO Demo Mission, a state-of-the-art project in collaboration with Mitsubishi Electric Corporation and Mitsubishi Electric US. […]

The post Terran Orbital to Deliver Nebula Bus for Mitsubishi Electric LEO Demo Mission appeared first on SpaceNews.

New study finds the label “commercial” masks sharp differences in risk, ownership and policy goals

The post What ‘commercial space’ really means depends on who’s buying — and why appeared first on SpaceNews.

Researchers at the ATLAS collaboration have been searching for signs of new particles in the dark sector of the universe, a hidden realm that could help explain dark matter. In some theories, this sector contains dark quarks (fundamental particles) that undergo a shower and hadronization process, forming long-lived dark mesons (dark quarks and antiquarks bound by a new dark strong force), which eventually decay into ordinary particles. These decays would appear in the detector as unusual “emerging jets”: bursts of particles originating from displaced vertices relative to the primary collision point.

Using 51.8 fb⁻¹ of proton–proton collision data at 13.6 TeV collected in 2022–2023, the ATLAS team looked for events containing two such emerging jets. They explored two possible production mechanisms, which are a vector mediator (Z′) produced in the s‑channel and a scalar mediator (Φ) exchanged in the t‑channel. The analysis combined two complementary strategies. A cut-based strategy relying on high-level jet observables, including track-, vertex-, and jet-substructure-based selections, enables a straightforward reinterpretation for alternative theoretical models. A machine learning approach employs a per-jet tagger using a transformer architecture trained on low-level tracking variables to discriminate emerging from Standard Model jets, maximizing sensitivity for the specific models studied.

No emerging‑jet signal excess was found, but the search set the first direct limits on emerging‑jet production via a Z′ mediator and the first constraints on t‑channel Φ production. Depending on the model assumptions, Z′ masses up to around 2.5 TeV and Φ masses up to about 1.35 TeV are excluded. These results significantly narrow the space in which dark sector particles could exist and form part of a broader ATLAS programme to probe dark quantum chromodynamics. The work sharpens future searches for dark matter and advances our understanding of how a dark sector might behave.

Search for emerging jets in pp collisions at √s = 13.6 TeV with the ATLAS experiment

The ATLAS Collaboration 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 097801

Dark matter and dark energy interactions: theoretical challenges, cosmological implications and observational signatures by B Wang, E Abdalla, F Atrio-Barandela and D Pavón (2016)

The post ATLAS narrows the hunt for dark matter appeared first on Physics World.

Active matter is matter composed of large numbers of active constituents, each of which consumes chemical energy in order to move or to exert mechanical forces.

This type of matter is commonly found in biology: swimming bacteria or migrating cells are both classic examples. In addition, a wide range of synthetic systems, such as active colloids or robotic swarms, can also fall into this umbrella.

Active matter has therefore been the focus of much research over the past decade, unveiling many surprising theoretical features and a suggesting a plethora of applications.

Perhaps most importantly, these systems’ ability to perform work leads to sustained non-equilibrium behaviour. This is distinctly different from that of relaxing equilibrium thermodynamic systems, commonly found in other areas of physics.

The concept of entropy production is often used to quantify this difference and to calculate how much useful work can be performed. If we want to harvest and utilise this work however, we need to understand the small-scale dynamics of the system. And it turns out this is rather complicated.

One way to calculate entropy production is through field theory, the workhorse of statistical mechanics. Traditional field theories simplify the system by smoothing out details, which works well for predicting densities and correlations. However, these approximations often ignore the individual particle nature, leading to incorrect results for entropy production.

The new paper details a substantial improvement on this method. By making use of Doi-Peliti field theory, they’re able to keep track of microscopic particle dynamics, including reactions and interactions.

The approach starts from the Fokker-Planck equation and provides a systematic way to calculate entropy production from first principles. It can be extended to include interactions between particles and produces general, compact formulas that work for a wide range of systems. These formulas are practical because they can be applied to both simulations and experiments.

The authors demonstrated their method with numerous examples, including systems of Active Brownian Particles, showing its broad usefulness. The big challenge going forward though is to extend their framework to non-Markovian systems, ones where future states depend on the present as well as past states.

Field theories of active particle systems and their entropy production – IOPscience

G. Pruessner and R. Garcia-Millan, 2025 Rep. Prog. Phys. 88 097601

The post How do bacteria produce entropy? appeared first on Physics World.

Quantum mechanics famously limits how much information about a system can be accessed at once in a single experiment. The more precisely a particle’s path can be determined, the less visible its interference pattern becomes. This trade-off, known as Bohr’s complementarity principle, has shaped our understanding of quantum physics for nearly a century. Now, researchers in China have brought one of the most famous thought experiments surrounding this principle to the quantum limit, using a single atom as a movable slit.

The thought experiment dates back to the 1927 Solvay Conference, where Albert Einstein proposed a modification of the double-slit experiment in which one of the slits could recoil. He argued that if a photon caused the slit to recoil as it passed through, then measuring that recoil might reveal which path the photon had taken without destroying the interference pattern. Conversely, Niels Bohr argued that any such recoil would entangle the photon with the slit, washing out the interference fringes.

For decades, this debate remained largely philosophical. The challenge was not about adding a detector or a label to track a photon’s path. Instead, the question was whether the “which-path” information could be stored in the motion of the slit itself. Until now, however, no physical slit was sensitive enough to register the momentum kick from a single photon.

To detect the recoil from a single photon, the slit’s momentum uncertainty must be comparable to the photon’s momentum. For any ordinary macroscopic slit, its quantum fluctuations are significantly larger than the recoil, washing out the which-path information. To give a sense of scale, the authors note that even a 1 g object modelled as a 100 kHz oscillator (for example, a mirror on a spring) would have a ground-state momentum uncertainty of about 10-16 kg m s-1, roughly 11 orders of magnitude larger than the momentum of an optical photon (approximately 10-27 kg m s-1).

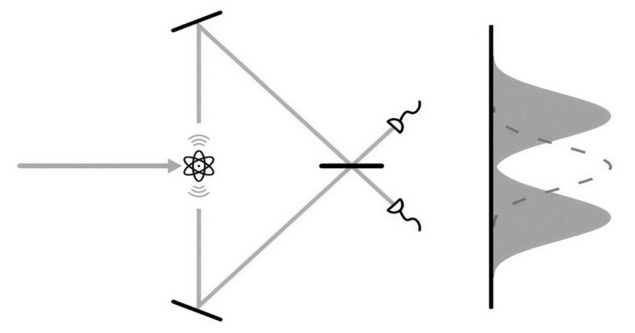

In their study, published in Physical Review Letters, Yu-Chen Zhang and colleagues from the University of Science and Technology of China overcame this obstacle by replacing the movable slit with a single rubidium atom held in an optical tweezer and cooled to its three-dimensional motional ground state. In this regime, the atom’s momentum uncertainty reaches the quantum limit, making the recoil from a single photon directly measurable.

Rather than using a conventional double-slit geometry, the researchers built an optical interferometer in which photons scattered off the trapped atom. By tuning the depth of this optical trap, the researchers were able to precisely control the atom’s intrinsic momentum uncertainty, effectively adjusting how “movable” the slit was.

As the researchers decreased the atom’s momentum uncertainty, they observed a loss of interference in the scattered photons. Increasing the atom’s momentum uncertainty caused the interference to reappear.

This behaviour directly revealed the trade-off between interference and which-path information at the heart of the Einstein–Bohr debate. The researchers note that the loss of interference arose not from classical noise, but from entanglement between the photon and the atom’s motion.

“The main challenge was matching the slit’s momentum uncertainty to that of a single photon,” says corresponding author Jian-Wei Pan. “For macroscopic objects, momentum fluctuations are far too large – they completely hide the recoil. Using a single atom cooled to its motional ground state allows us to reach the fundamental quantum limit.”

Maintaining interferometric phase stability was equally demanding. The team used active phase stabilization with a reference laser to keep the optical path length stable to within a few nanometres (roughly 3 nm) for over 10 h.

Beyond settling a historical argument, the experiment offers a clean demonstration of how entanglement plays a key role in Bohr’s complementarity principle. As Pan explains, the results suggest that “entanglement in the momentum degree-of-freedom is the deeper reason behind the loss of interference when which-path information becomes available”.

This experiment opens the door to exploring quantum measurement in a new regime. By treating the slit itself as a quantum object, future studies could probe how entanglement emerges between light and matter. Additionally, the same set-up could be used to gradually increase the mass of the slit, providing a new way to study the transition from quantum to classical behaviour.

The post Einstein’s recoiling slit experiment realized at the quantum limit appeared first on Physics World.

Mission marks third consecutive GPS launch reassigned from ULA to SpaceX

The post SpaceX launches GPS satellite for U.S. Space Force appeared first on SpaceNews.

BRUSSELS — Exotrail, a French company specializing in multi-orbit satellite mobility and focused on LEO service vehicles, together with Astroscale France, the French subsidiary of the Japan-based on-orbit servicing company, announced Jan. 28 a partnership aimed at testing deorbiting capabilities in low Earth orbit. The mission itself has not yet been fully approved. “We are […]

The post Exotrail and Astroscale France join forces to build deorbiting capability for LEO appeared first on SpaceNews.