Viruses on Plastic Pollution May Be Fueling Antibiotic Resistance

China is aiming for a first launch of a reusable, cargo-optimized variant of its new crew launch vehicle in the first half of the year.

The post China to debut reusable Long March 10-derived rocket in first half of 2026 appeared first on SpaceNews.

From cutting onions to a LEGO Jodrell Bank, physics has had its fair share of quirky stories this year. Here is our pick of the best, not in any particular order.

Researchers in the US this year discovered that a tiny jumping worm uses static electricity to increase its chances of attaching to unsuspecting prey. The parasitic roundworm Steinernema carpocapsae can leap some 25 times its body length by curling into a loop and springing in the air. If the nematode lands successfully on a victim, it releases bacteria that kills the insect within a couple of days upon which the worm feasts and lays its eggs. To investigate whether static electricity aids their flight, a team at Emory University and the University of California, Berkeley, used high-speed microscopy to film the worms as they leapt onto a fruit fly that was tethered with a copper wire connected to a high-voltage power supply. The researchers found that a charge of a few hundred volts – similar to that generated in the wild by an insect’s wings rubbing against ions in the air – fosters a negative charge on the worm, creating an attractive force with the positively charged fly. They discovered that without any electrostatics, only 1 in 19 worm trajectories successfully reached their target. The greater the voltage, however, the greater the chance of landing with 880 V resulting in an 80% probability of success. “We’re helping to pioneer the emerging field of electrostatic ecology,” notes Emory physicist Ranjiangshang Ran.

While it is known that volatile chemicals released from onions irritate the nerves in the cornea to produce tears, how such chemical-laden droplets reach the eyes and whether they are influenced by the knife or cutting technique remain less clear. To investigate, Sunghwan Jung from Cornell University and colleagues built a guillotine-like apparatus and used high-speed video to observe the droplets released from onions as they were cut by steel blades. They found that droplets, which can reach up to 60 cm high, were released in two stages – the first being a fast mist-like outburst that was followed by threads of liquid fragmenting into many droplets. The most energetic droplets were released during the initial contact between the blade and the onion’s skin. When they began varying the sharpness of the blade and the cutting speed, they discovered that a greater number of droplets were released by blunter blades and faster cutting speeds. “That was even more surprising,” notes Jung. “Blunter blades and faster cuts – up to 40 m/s – produced significantly more droplets with higher kinetic energy.” Another surprise was that refrigerating the onions prior to cutting also produced an increased number of droplets of similar velocity, compared to room-temperature vegetables.

Students at the University of Manchester in the UK created a 30 500-piece LEGO model of the iconic Lovell Telescope to mark the 80th anniversary of the Jodrell Bank Observatory, which was founded in December 1945. Built in 1957, the 76.2 m diameter telescope was the largest steerable dish radio telescope in the world at the time. The LEGO model has been designed by Manchester’s undergraduate physics society and is based on the telescope’s original engineering blueprints. Student James Ruxton spent six months perfecting the design, which even involved producing custom-designed LEGO bricks with a 3D printer. Ruxton and fellow students began construction in April and the end result is a model weighing 30 kg with 30500 pieces and a whopping 4000-page instruction manual. “It’s definitely the biggest and most challenging build I’ve ever done, but also the most fun,” says Ruxton. “I’ve been a big fan of LEGO since I was younger, and I’ve always loved creating my own models, so recreating something as iconic as the Lovell is like taking that to the next level!” The model has gone on display in a “specially modified cabinet” at the university’s Schuster building, taking pride of place alongside a decade-old LEGO model of CERN’s ATLAS detector.

The curves and curls of leaves and flower petals arise due to the interplay between their natural growth and geometry. Uneven growth in a flat sheet, in which the edges grow quicker than the interior, gives rise to strain and in plant leaves and petals, for example, this can result in a variety of shapes such as saddle and ripple shapes. Yet when it comes to rose petals, the sharply pointed cusps – a point where two curves meet – that form at the edge of the petals set it apart from soft, wavy patterns seen in many other plants.

To investigate this intriguing difference, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem carried out theoretical modelling and conducted a series of experiments with synthetic disc “petals”. They found that the pointed cusps that form at the edge of rose petals are due to a type of geometric frustration called a Mainardi–Codazzi–Peterson (MCP) incompatibility. This type of mechanism results in stress concentrating in a specific area, which goes on to form cusps to avoid tearing or forming unnatural folding. When the researchers suppressed the formation of cusps, they found that the discs revert to being smooth and concave. The researchers say that the findings could be used for applications in soft robotics and even in the deployment of spacecraft components.

The Wild Cards universe is a series of novels set largely during an alternate history of the US following the Second World War. The series follows events after an extraterrestrial virus, known as the Wild Card virus, has spread worldwide. It mutates human DNA causing profound changes in human physiology. The virus follows a fixed statistical distribution in that 90% of those infected die, 9% become physically mutated (referred to as “jokers”) and 1% gain superhuman abilities (known as “aces”). Such capabilities include the ability to fly as well as being able to move between dimensions. George R R Martin, the author who co-edits the Wild Cards series, co-authored a paper examining the complex dynamics of the Wild Card virus together with Los Alamos National Laboratory theoretical physicist Ian Tregillis, who is also a science-fiction author. The model takes into consideration the severity of the changes (for the 10% that don’t instantly die) and the mix of joker/ace traits. The result is a dynamical system in which a carrier’s state vector constantly evolves through the model space – until their “card” turns. At that point the state vector becomes fixed and its permanent location determines the fate of the carrier. “The fictional virus is really just an excuse to justify the world of Wild Cards, the characters who inhabit it, and the plot lines that spin out from their actions,” says Tregillis.

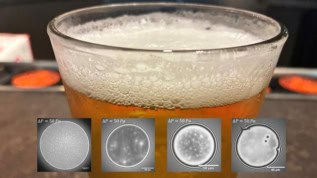

And finally, a clear sign of a good brew is a big head of foam at the top of a poured glass. Beer foam is made of many small bubbles of air, separated from each other by thin films of liquid. These thin films must remain stable, or the bubbles will pop, and the foam will collapse. What holds these thin films together is not completely understood and is likely conglomerates of proteins, surface viscosity or the presence of surfactants – molecules that can reduce surface tension and are found in soaps and detergents. To find out more, researchers from ETH Zurich and Eindhoven University of Technology investigated beer-foam stability for different types of beers at varying stages of the fermentation process. They found that for single-fermentation beers, the foams are mostly held together with the surface viscosity of the beer. This is mostly influenced by the proteins in the beer – the more they contain, the more viscous the film and more stable the foam will be. However, for double-fermented beers, the proteins in the beer are slightly denatured by the yeast cells and come together to form a two-dimensional membrane that keeps the foam intact longer. The head was found to be even more stable for triple-fermented beers, which include Trappist beers. The team says that the work could be used to identify ways to increase or decrease the amount of foam so that everyone can pour a perfect glass of beer every time. Cheers!

You can be sure that 2026 will throw up its fair share of quirky stories from the world of physics. See you next year!

The post The quirkiest stories from the world of physics in 2025 appeared first on Physics World.

China reached 92 orbital launches in 2025 with back-to-back missions this week, capping a record year for both the country and the global space sector.

The post China caps record year for orbital launches with Tianhui-7 and Shijian-29 technology test missions appeared first on SpaceNews.

Space Forge said Dec. 31 it generated plasma aboard its first satellite, a milestone the British startup says shows it can create and maintain conditions needed to produce valuable semiconductor materials in LEO.

The post Space Forge generates plasma for LEO semiconductor material production appeared first on SpaceNews.

Planet, a company best known for providing geospatial intelligence through its constellation of imaging satellites, sees a significant opportunity in developing orbital data centers for artificial intelligence.

The post Planet bets on orbital data centers in partnership with Google appeared first on SpaceNews.

Vandenberg Space Force Base is offering launch providers access to a new site with conditions that could enable flights of SpaceX’s Starship.

The post Space Force offers new Vandenberg launch site appeared first on SpaceNews.

MILAN — The European Space Agency has confirmed a security breach of unclassified material from science servers following reports on social media. A threat actor claimed to have compromised ESA systems and to have leaked roughly 200 gigabytes of data. According to screenshots shared on X by French cybersecurity professional Seb Latom, the actor alleges […]

The post ESA confirms data breach appeared first on SpaceNews.

Popularity isn’t everything. But it is something, so for the second year running, we’re finishing our trip around the Sun by looking back at the physics stories that got the most attention over the past 12 months. Here, in ascending order of popularity, are the 10 most-read stories published on the Physics World website in 2025.

We’ve had quantum science on our minds all year long, courtesy of 2025 being UNESCO’s International Year of Quantum Science and Technology. But according to theoretical work by Partha Ghose and Dimitris Pinotsis, it’s possible that the internal workings of our brains could also literally be driven by quantum processes.

Though neurons are generally regarded as too big to display quantum effects, Ghose and Pinotsis established that the equations describing the classical physics of brain responses are mathematically equivalent to the equations describing quantum mechanics. They also derived a Schrödinger-like equation specifically for neurons. So if you’re struggling to wrap your head around complex quantum concepts, take heart: it’s possible that your brain is ahead of you.

Einstein famously disliked the idea of quantum entanglement, dismissing its effects as “spooky action at a distance”. But would he have liked the idea of an extra time dimension any better? We’re not sure he would, but that is the solution proposed by theoretical physicist Marco Pettini, who suggests that wavefunction collapse could propagate through a second time dimension. Pettini got the idea from discussions with the Nobel laureate Roger Penrose and from reading old papers by David Bohm, but not everyone is impressed by these distinguished intellectual antecedents. In this article, Bohm’s former student and frequent collaborator Jeffrey Bub went on the record to say he “wouldn’t put any money on” Pettini’s theory being correct. Ouch.

Continuing the theme of intriguing, blue-sky theoretical research, the eighth-most-read article of 2025 describes how two theoretical physicists, Kaden Hazzard and Zhiyuan Wang, proposed a new class of quasiparticles called paraparticles. Based on their calculations, these paraparticles exhibit quantum properties that are fundamentally different from those of bosons and fermions. Notably, paraparticles strikes a balance between the exclusivity of fermions and the clustering tendency of bosons, with up to two paraparticles allowed to occupy the same quantum state (rather than zero for fermions or infinitely many for bosons). But do they really exist? No-one knows yet, but Hazzard and Wang say that experimental studies of ultracold atoms could hold the answer.

The list of early Nobel laureates in physics is full of famous names – Roentgen, Curie, Becquerel, Rayleigh and so on. But if you go down the list a little further, you’ll find that the 1908 prize went to a now mostly forgotten physicist by the name of Gabriel Lippmann, for a version of colour photography that almost nobody uses (though it’s rather beautiful, as the photo shows). This article tells the story of how and why this happened. A companion piece on the similarly obscure 1912 laureate, Gustaf Dalén, fell just outside this year’s top 10; if you’re a member of the Institute of Physics, you can read both of them together in the November issue of Physics World.

Why should physicists have all the fun of learning about the quantum world? This episode of the Physics World Weekly podcast focuses on the outreach work of Aleks Kissinger and Bob Coecke, who developed a picture-driven way of teaching quantum physics to a group of 15-17-year-old students. One of the students in the original pilot programme, Arjan Dhawan, is now studying mathematics at the University of Durham, and he joined his former mentors on the podcast to answer the crucial question: did it work?

Niels Bohr had many good ideas in his long and distinguished career. But he also had a few that didn’t turn out so well, and this article by science writer Phil Ball focuses on one of them. Known as the Bohr-Kramers-Slater (BKS) theory, it was developed in 1923 with help from two of the assistants/students/acolytes who flocked to Bohr’s institute in Copenhagen. Several notable physicists hated it because it violated both causality and the conservation of energy, and within two years, experiments by Walther Boethe and Hans Geiger proved them right. The twist, though, is that Boethe went on to win a share of the 1954 Nobel Prize for Physics for this work – making Bohr surely one of the only scientists who won himself a Nobel Prize for his good ideas, and someone else a Nobel Prize for a bad one.

Black holes are fascinating objects in their own right. Who doesn’t love the idea of matter-swallowing cosmic maws floating through the universe? For some theoretical physicists, though, they’re also a way of exploring – and even extending – Einstein’s general theory of relativity. This article describes how thinking about black hole collisions inspired Jiaxi Wu, Siddharth Boyeneni and Elias Most to develop a new formulation of general relativity that mirrors the equations that describe electromagnetic interactions. According to this formulation, general relativity behaves the same way as the gravitational described by Isaac Newton more than 300 years ago, with the “gravito-electric” field fading with the inverse square of distance.

“Best of” lists are a real win-win. If you agree with the author’s selections, you go away feeling confirmed in your mutual wisdom. If you disagree, you get to have a good old moan about how foolish the author was for forgetting your favourites or including something you deem unworthy. Either way, it’s a success – as this very popular list of the top 5 Nobel Prizes for Physics awarded since the year 2000 (as chosen by Physics World editor-in-chief Matin Durrani) demonstrates.

We’re back to black holes again for the year’s second-most-read story, which focuses on a possible link between gravity and quantum information theory via the concept of entropy. Such a link could help explain the so-called black hole information paradox – the still-unresolved question of whether information that falls into a black hole is retained in some form or lost as the black hole evaporates via Hawking radiation. Fleshing out this connection could also shed light on quantum information theory itself, and the theorist who’s proposing it, Ginestra Bianconi, says that experimental measurements of the cosmological constant could one day verify or disprove it.

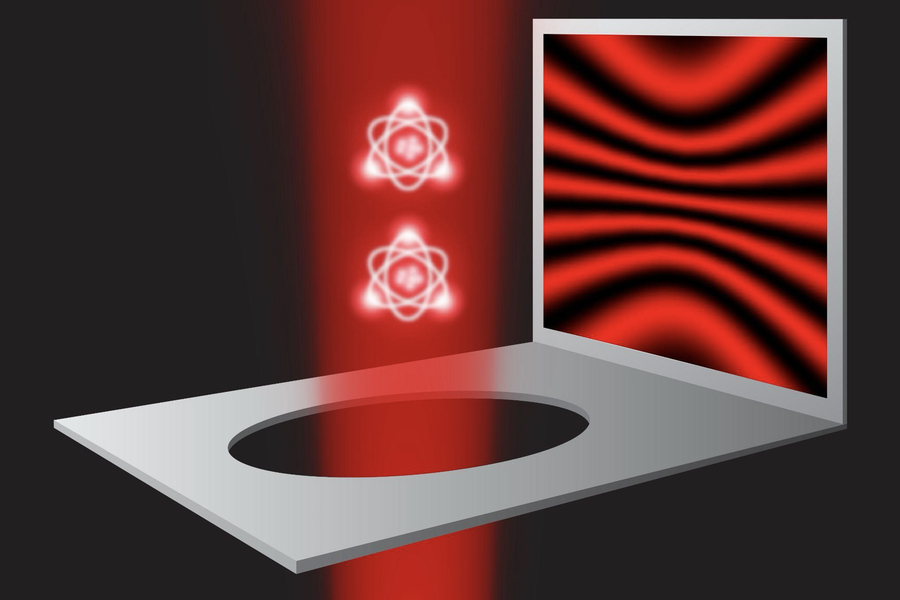

Back in 2002, readers of Physics World voted Thomas Young’s electron double-slit experiment “the most beautiful experiment in physics”. More than 20 years later, it continues to fascinate the physics community, as this, the most widely read article of any that Physics World published in 2025, shows.

Young’s original experiment demonstrated the wave-like nature of electrons by sending them through a pair of slits and showing that they create an interference pattern on a screen even when they pass through the slits one-by-one. In this modern update, physicists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), US, stripped this back to the barest possible bones.

Using two single atoms as the slits, they inferred the path of photons by measuring subtle changes in the atoms’ properties after photon scattering. Their results matched the predictions of quantum theory: interference fringes when they didn’t observe the photons’ path, and two bright spots when they did.

It’s an elegant result, and the fact that the MIT team performed the experiment specifically to celebrate the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology 2025 makes its popularity with Physics World readers especially gratifying.

So here’s to another year full of elegant experiments and the theories that inspire them. Long may they both continue, and thank you, as always, for taking the time to read about them.

The post Winning the popularity contest: the 10 most-read physics stories of 2025 appeared first on Physics World.

In this episode of Space Minds, host Mike Gruss is joined by SpaceNews journalists Jason Rainbow, Sandra Erwin, Jeff Foust and Debra Werner for a wide-ranging conversation on the space stories that will define the year ahead.

The post The space stories that will shape 2026 appeared first on SpaceNews.

Our blue planet is a Goldilocks world. We’re at just the right distance from the Sun that Earth – like Baby Bear’s porridge – is not too hot or too cold, allowing our planet to be bathed in oceans of liquid water. But further out in our solar system are icy moons that eschew the Goldilocks principle, maintaining oceans and possibly even life far from the Sun.

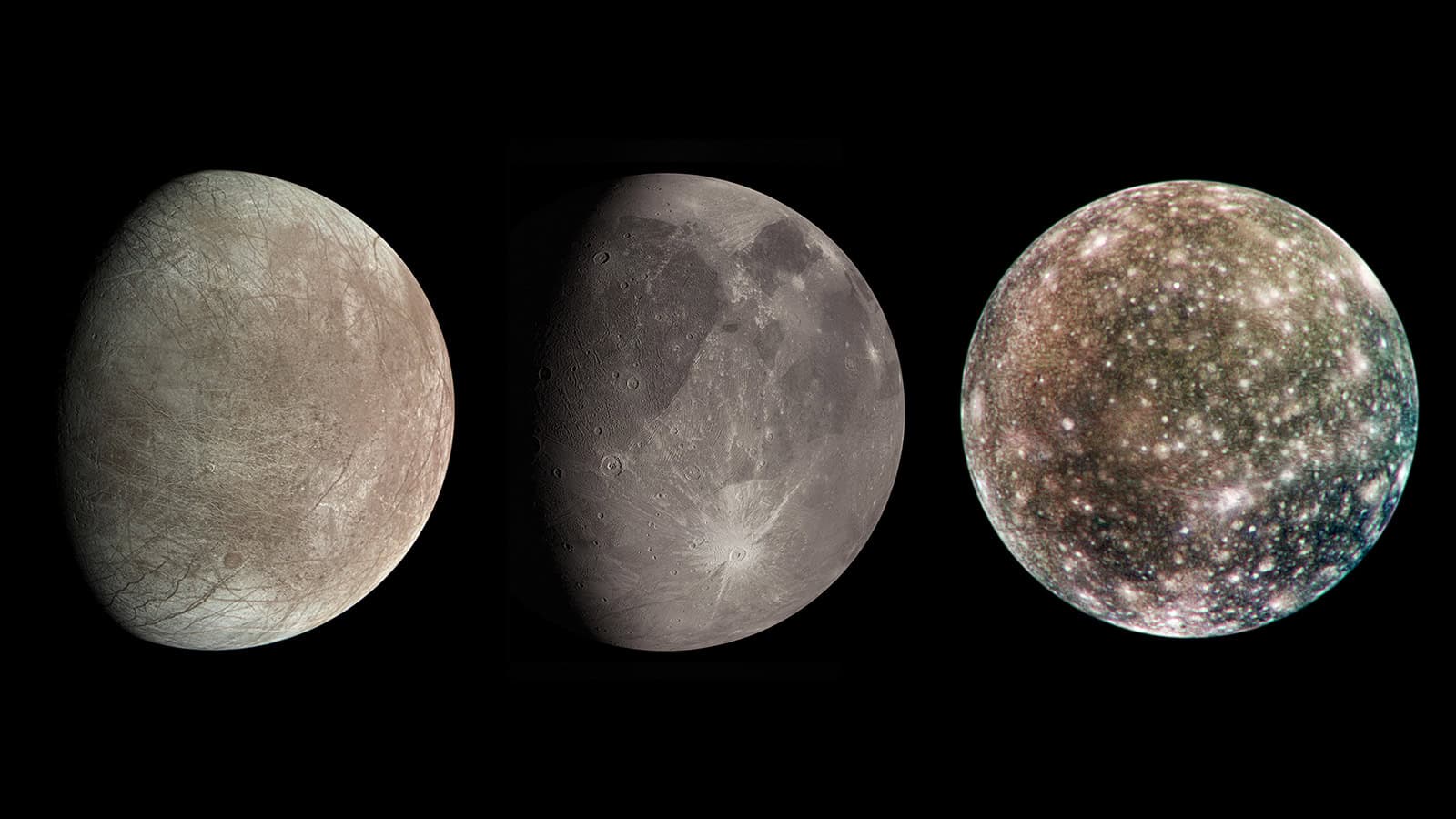

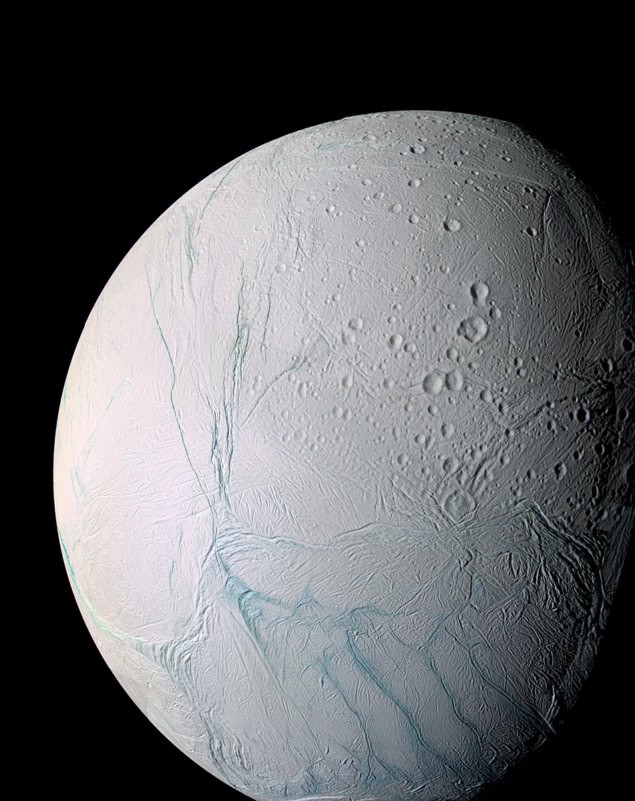

We call them icy moons because their surface, and part of their interior, is made of solid water-ice. There are over 400 icy moons in the solar system – most are teeny moonlets just a few kilometres across, but a handful are quite sizeable, from hundreds to thousands of kilometres in diameter. Of the big ones, the best known are Jupiter’s moons, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, and Saturn’s Titan and Enceladus.

Yet these moons are more than just ice. Deep beneath their frozen shells – some –160 to –200 °C cold and bathed in radiation – lie oceans of water, kept liquid thanks to tidal heating as their interiors flex in the strong gravitational grip of their parent planets. With water being a prerequisite for life as we know it, these frigid systems are our best chance for finding life beyond Earth.

The first hints that these icy moons could harbour oceans of liquid water came when NASA’s Voyager 1 and 2 missions flew past Jupiter in 1979. On Europa they saw a broken and geologically youthful-looking surface, just millions of years old, featuring dark cracks that seemed to have slushy material welling up from below. Those hints turned into certainty when NASA’s Galileo mission visited Jupiter between 1995 and 2003. Gravity and magnetometer experiments proved that not only does Europa contain a liquid layer, but so do Ganymede and Callisto.

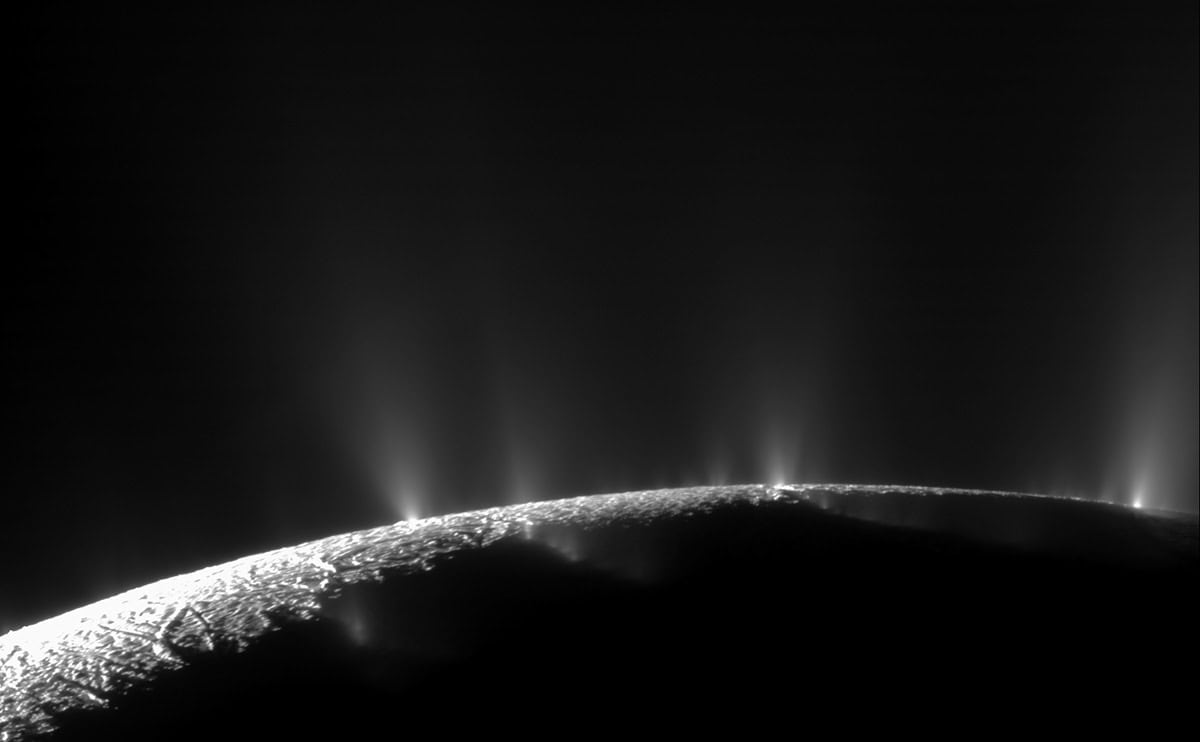

Meanwhile at Saturn, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft (which arrived in 2004) encountered disturbances in the ringed planet’s magnetic field. They turned out to be caused by plumes of water vapour erupting out of giant fractures splitting the surface of Enceladus, and it is believed that this vapour originates from an ocean beneath the moon’s ice shell. Evidence for an ocean on Titan is a little less certain, but gravity and radio measurements performed by Cassini and its European-built lander Huygens point towards the possibility of some liquid or slushy water beneath the surface.

“All of these ocean worlds are going to be different, and we have to go to all of them to understand the whole spectrum of icy moons,” says Amanda Hendrix, director of the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona, US. “Understanding what their oceans are like can tell us about habitability in the solar system and where life can take hold and evolve.”

To that end, an armada of spacecraft will soon be on their way to the icy moons of the outer planets, building on the successes of their predecessors Voyager, Galileo and Cassini–Huygens. Leading the charge is NASA’s Europa Clipper, which is already heading to Jupiter. Clipper will reach its destination in 2030, with the Jupiter Icy moons Explorer (JUICE) from the European Space Agency (ESA) just a year behind it. Europa is the primary target of scientists because it is possibly Jupiter’s most interesting moon as a result of its “astrobiological potential”. That’s the view of Olivier Witasse, who is JUICE project scientist at ESA, and it’s why Europa Clipper will perform nearly 50 fly-bys of the icy moon, some as low as 25 km above the surface. JUICE will also visit Europa twice on its tour of the Jovian system.

The challenge at Europa is that it’s close enough to Jupiter to be deep inside the giant planet’s magnetosphere, which is loaded with high-energy charged particles that bathe the moon’s surface in radiation. That’s why Clipper and JUICE are limited to fly-bys; the radiation dose in orbit around Europa would be too great to linger. Clipper’s looping orbit will take it back out to safety each time. Meanwhile, JUICE will focus more on Callisto and Ganymede – which are both farther out from Jupiter than Europa is – and will eventually go into orbit around Ganymede.

“Ganymede is a super-interesting moon,” says Witasse. For one thing, at 5262 km across it is larger than Mercury, a planet. It also has its own intrinsic magnetic field – one of only three solid bodies in the solar system to do so (the others being Mercury and Earth).

It’s the interiors of these moons that are of the most interest to JUICE and Clipper. That’s where the oceans are, hidden beneath many kilometres of ice. While the missions won’t be landing on the Jovian moons, these internal structures aren’t as inaccessible as we might at first think. In fact, there are three independent methods for probing them.

If a moon’s ocean contains salts or other electrically conductive contaminants, interesting things happen when passing through the parent planet’s variable magnetic field. “The liquid is a conductive layer within a varying magnetic field and that induces a magnetic field in the ocean that we can measure with a magnetometer using Faraday’s law,” says Witasse. The amount of salty contaminants, plus the depth of the ocean, influence the magnetometer readings.

Then there’s radio science – the way that an icy moon’s mass bends a radio signal from a spacecraft to Earth. By making multiple fly-bys with different trajectories during different points in a moon’s orbit around its planet, the moon’s gravity field can be measured. Once that is known to exacting detail, it can be applied to models of that moon’s internal structure.

Perhaps the most remarkable method, however, is using a laser altimeter to search for a tidal bulge in the surface of a moon. This is exactly what JUICE will be doing when in orbit around Ganymede. Its laser altimeter will map the shape of the surface – such as hills and crevasses – but gravitational tidal forces from Jupiter are expected to cause a bulge on the surface, deforming it by 1–10 m. How large the bulge is depends upon how deep the ocean is.

“If the surface ice is sitting above a liquid layer then the tide will be much bigger because if you sit on liquid, you are not attached to the rest of the moon,” says Witasse. “Whereas if Ganymede were solid the tide would be quite small because it is difficult to move one big, solid body.”

As for what’s below the oceans, those same gravity and radio-science experiments during previous missions have given us a general idea about the inner structures of Jupiter’s Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. All three have a rocky core. Inside Europa, the ocean surrounds the core, with a ceiling of ice above it. The rock–ocean interface potentially provides a source of chemical energy and nutrients for the ocean and any life there.

Ganymede’s interior structure is more complex. Separating the 3400 km-wide rocky core and the ocean is a layer, or perhaps several layers, of high-pressure ice, and there is another ice layer above the ocean. Without that rock–ocean interface, Ganymede is less interesting from an astrobiological perspective.

Meanwhile, Callisto, being the farthest from Jupiter, receives the least tidal heating of the three. This is reflected in Callisto’s lack of evolution, with its interior having not differentiated into layers as distinct as Europa and Ganymede. “Callisto looks very old,” says Witasse. “We’re seeing it more or less as it was at the beginning of the solar system.”

Tidal forces don’t just keep the interiors of the icy moons warm. They can also drive dramatic activity, such as cryovolcanoes – icy eruptions that spew out gases and volatile materials like liquid water (which quickly freezes in space), ammonia and hydrocarbons. The most obvious example of this is found on Saturn’s Enceladus, where giant water plumes squirt out through “tiger stripe” cracks at the moon’s south pole.

But there’s also growing evidence of cryovolcanism on Europa. In 2012 the Hubble Space Telescope caught sight of what looked like a water plume jetting out 200 km from the moon. But the discovery is controversial despite more data from Hubble and even supporting evidence found in archive data from the Galileo mission. What’s missing is cast-iron proof for Europa’s plumes. That’s where Clipper comes in.

“We need to find out if the plumes are real,” says Hendrix. “What we do know is if there is plume activity happening on Europa then it’s not as consistent or ongoing as is clearly happening at Enceladus.”

At Enceladus, the plumes are driven by tidal forces from Saturn, which squeeze and flex the 500 km-wide moon’s innards, forcing out water from an underground ocean through the tiger stripes. If there are plumes at Europa then they would be produced the same way, and would provide access to material from an ocean that’s dozens of kilometres below the icy crust. “I think we have a lot of evidence that something is happening at Europa,” says Hendrix.

These plumes could therefore be the key to characterizing the hidden oceans. One instrument on Clipper that will play an important role in investigating the plumes at Europa is an ultraviolet spectrometer, a technique that was very useful on the Cassini mission.

Because Enceladus’ plumes were not known until Cassini discovered them, the spacecraft’s instruments had not been designed to study them. However, scientists were able to use the mission’s ultraviolet imaging spectrometer to analyse the vapour when it was between Cassini and the Sun. The resulting absorption lines in the spectrum showed the plumes to be mostly pure water, ejected into space at a rate of 200 kg per second.

The erupted vapour freezes as it reaches space and some of it snows back down onto the surface. Cassini’s ultraviolet spectrometer was again used, this time to detect solar ultraviolet light reflected and scattered off these icy particles in the uppermost layers of Enceladus’ surface. Scientists found that any freshly deposited snow from the plumes has a different chemistry from older surface material that has been weathered and chemically altered by micrometeoroids and radiation, and therefore a different ultraviolet spectrum.

Another two instruments that Cassini’s scientists adapted to study the plumes were the cosmic dust analyser, and the ion and neutral mass spectrometer. When Cassini flew through the fresh plumes and Saturn’s E-ring, which is formed from older plume ejections, it could “taste” the material by sampling it directly. Recent findings from this data indicate that the plumes are rich in salt as well as organic molecules, including aliphatic and cyclic esters and ethers (carbon-bonded acid-based compounds such as fatty acids) (Nature Astron. 9 1662). Scientists also found nitrogen- and oxygen-bearing compounds that play a role in basic biochemistry and which could therefore potentially be building blocks of prebiotic molecules or even life in Enceladus’ ocean.

While Cassini could only observe Enceladus’ plumes and fresh snow from orbit, astronomers are planning a lander that could let them directly inspect the surface snow. Currently in the technology development phase, it would be launched by ESA sometime in the 2040s to arrive at the moon in 2054, when winter at Enceladus’ southern, tiger stripe-adorned pole turns to spring and daylight returns.

“What makes the mission so exciting to me is that although it looks like every large icy moon has an ocean, Enceladus is one where there is a very high chance of actually sampling ocean water,” says Jörn Helbert, head of the solar system section at ESA, and the science lead on the prospective mission.

The planned spacecraft will fly through the plumes with more sophisticated instruments than Cassini’s, designed specifically to sample the vapour (like Clipper will do at Europa). Yet adding a lander could get us even closer to the plume material. By landing close to the edge of a tiger stripe, a lander would dramatically increase the mission’s ability to analyse the material from the ocean in the form of fresh snow. In particular, it would look for biosignatures – evidence of the ocean being habitable, or perhaps even inhabited by microbes.

However, new research urges caution in drawing hasty conclusions about organic molecules present in the plumes and snow. While not as powerful as Jupiter’s, Saturn also has a magnetosphere filled with high-energy ions that bombard Enceladus. A recent laboratory study, led by Grace Richards of the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziale (IAPS-INAF) in Rome, found that when these ions hit surface-ice they trigger chemical reactions that produce organic molecules, including some that are precursors to amino acids, similar to what Cassini tasted in the plumes.

So how can we be sure that the organics in Enceladus’ plumes originate from the ocean, and not from radiation-driven chemistry on the surface? It is the same quandary for dark patches around cracks on the surface of Europa, which seem to be rich with organic molecules that could either originate via upwelling from the ocean below, or just from radiation triggering organic chemistry. A lander on Enceladus might solve not just the mystery of that particular moon, but provide important pointers to explain what we’re seeing on Europa too.

Enceladus is not Saturn’s only icy moon; there’s Titan too. As the ringed planet’s largest moon at 5150 km across, Titan (like Ganymede) is larger than Mercury. However, unlike the other moons in the solar system, Titan has a thick atmosphere rich in nitrogen and methane. The atmosphere is opaque, hiding the surface from spacecraft in orbit except at infrared wavelengths and radar, which means that getting below the smoggy atmosphere is a must.

ESA did this in 2005 with the Huygens lander, which, as it parachuted down to Titan’s frozen surface, revealed it to be a land of hills and dune plains with river channels, lakes and seas of flowing liquid hydrocarbons. These organic molecules originate from the methane in its atmosphere reacting with solar ultraviolet.

Until recently, it was thought that Titan has a core of rock, surrounded by a shell of high-pressure ice, above which sits a layer of salty liquid water and then an outer crust of water ice. However, new evidence from re-analysing Cassini’s data suggests that rather than oceans of liquid water, Titan has “slush” below the frozen exterior, with pockets of liquid water (Nature 648 556). The team, led by Flavio Petricca from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, looked at how Titan’s shape morphs as it orbits Saturn. There is a several-hour lag between the moon passing the peak of Saturn’s gravitational pull and its shape shifting, implying that while there must be some form of non-solid substance below Titan’s surface to allow for deformation, more energy is lost or dissipated than would be if it was liquid water. Instead, the researchers found that a layer of high-pressure ice close to its melting point – or slush – better fits the data.

To find out more about Titan, NASA is planning to follow in Huygens’ footsteps with the Dragonfly mission but in an excitingly different way. Set to launch in 2028, Dragonfly should arrive at Titan in 2034 where it will deploy a rotorcraft that will fly over the moon’s surface, beneath the smog, occasionally touching down to take readings. Scientists are intending to use Dragonfly to sample surface material with a mass spectrometer to identify organic compounds and therefore better assess Titan’s biological potential. It will also perform atmospheric and geological measurements, even listening for seismic tremors while landed, which could provide further clues about Titan’s interior.

Jupiter and Saturn are also not the only planets to possess icy moons. We find them around Uranus and Neptune too. Even the dwarf planet Pluto and its largest moon Charon have strong similarities to icy moons. Whether any of these bodies, so far out from the Sun, can maintain an ocean is unclear, however.

Recent findings point to an ocean deep inside Uranus’ moon Ariel that may once have been 170 km deep, kept warm by tidal heating (Icarus 444 116822). But over time Ariel’s orbit around Uranus has become increasingly circular, weakening the tidal forces acting on it, and the ocean has partly frozen. Another of Uranus’ moons, Miranda, has a chaotic surface that appears to have melted and refrozen, and the pattern of cracks on its surface strongly suggests that the moon also contains an ocean, or at least did 150 million years ago. A new mission to Uranus is a top priority in the US’s most recent Decadal Review.

It’s becoming clear that icy ocean moons could far outnumber more traditional habitable planets like Earth, not just in our solar system, but across the galaxy (although none have been confirmed yet). Understanding the internal structures of the icy moons in our solar system, and characterizing their oceans, is vital if we are to expand the search for life beyond Earth.

The post Exploring the icy moons of the solar system appeared first on Physics World.