Vue lecture

Staying the course with lockdowns could end future pandemics in months

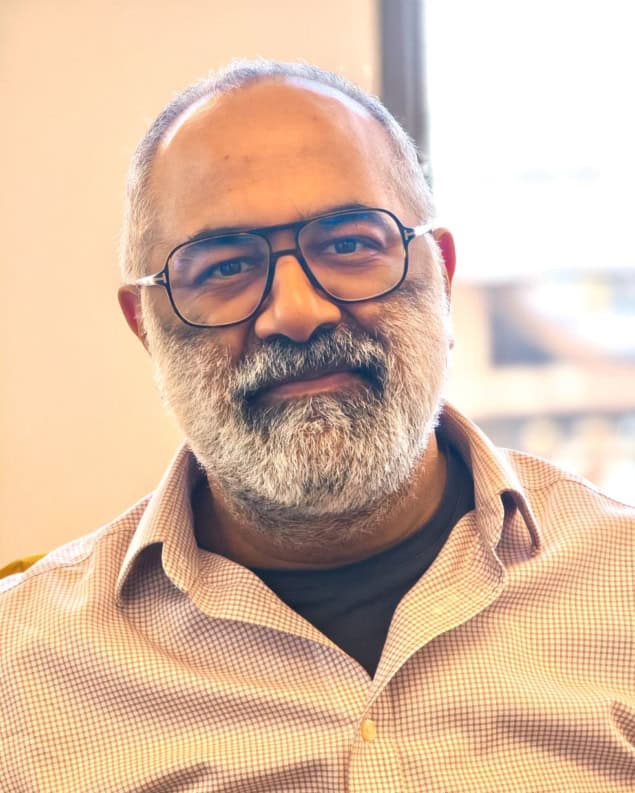

As a theoretical and mathematical physicist at Imperial College London, UK, Bhavin Khatri spent years using statistical physics to understand how organisms evolve. Then the COVID-19 pandemic struck, and like many other scientists, he began searching for ways to apply his skills to the crisis. This led him to realize that the equations he was using to study evolution could be repurposed to model the spread of the virus – and, crucially, to understand how it could be curtailed.

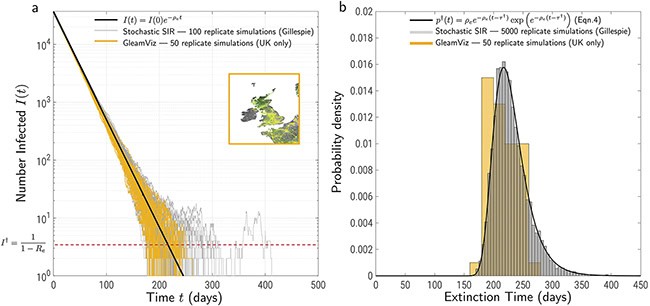

In a paper published in EPL, Khatri models the spread of a SARS-CoV-2-like virus using branching process theory, which he’d previously used to study how advantageous alleles (variations in a genetic sequence) become more prevalent in a population. He then uses this model to assess the duration that interventions such as lockdowns would need to be applied in order to completely eliminate infections, with the strength of the intervention measured in terms of the number of people each infected person goes on to infect (the virus’ effective reproduction number, R).

Tantalizingly, the paper concludes that applying such interventions worldwide in June 2020 could have eliminated the COVID virus by January 2021, several months before the widespread availability of vaccines reduced its impact on healthcare systems and led governments to lift restrictions on social contact. Physics World spoke to Khatri to learn more about his research and its implications for future pandemics.

What are the most important findings in your work?

One important finding is that we can accurately calculate the distribution of times required for a virus to become extinct by making a relatively simple approximation. This approximation amounts to assuming that people have relatively little population-level “herd” immunity to the virus – exactly the situation that many countries, including the UK, faced in March 2020.

Making this approximation meant I could reduce the three coupled differential equations of the well-known SIR model (which models pandemics via the interplay between Susceptible, Infected and Recovered individuals) to a single differential equation for the number of infected individuals in the population. This single equation turned out to be the same one that physics students learn when studying radioactive decay. I then used the discrete stochastic version of exponential decay and standard approaches in branching process theory to calculate the distribution of extinction times.

Alongside the formal theory, I also used my experience in population genetic theory to develop an intuitive approach for calculating the mean of this extinction time distribution. In population genetics, when a mutation is sufficiently rare, changes in its number of copies in the population are dominated by randomness. This is true even if the mutation has a large selective advantage: it has to grow by chance to sufficient critical size – on the order of 1/(selection strength) – for selection to take hold.

The same logic works in reverse when applied to a declining number of infections. Initially, they will decline deterministically, but once they go below a threshold number of individuals, changes in infection numbers become random. Using the properties of such random walks, I calculated an expression for the threshold number and the mean duration of the stochastic phase. These agree well with the formal branching process calculation.

In practical terms, the main result of this theoretical work is to show that for sufficiently strong lockdowns (where, on average, only one of every two infected individuals goes on to infect another person, R=0.5), this distribution of extinction times was narrow enough to ensure that the COVID pandemic virus would have gone extinct in a matter of months, or at most a year.

How realistic is this counterfactual scenario of eliminating SARS-CoV-2 within a year?

Leaving politics and the likelihood of social acceptance aside for the moment, if a sufficiently strong lockdown could have been maintained for a period of roughly six months across the globe, then I am confident that the virus could have been reduced to very low levels, or even made extinct.

The question then is: is this a stable situation? From the perspective of a single nation, if the rest of the world still has infections, then that nation either needs to maintain its lockdown or be prepared to re-impose it if there are new imported cases. From a global perspective, a COVID-free world should be a stable state, unless an animal reservoir of infections causes re-infections in humans.

As for the practical success of such a strategy, that depends on politics and the willingness of individuals to remain in lockdown. Clearly, this is not in the model. One thing I do discuss, though, is that this strategy becomes far more difficult once more infectious variants of SARS-CoV-2 evolve. However, the problem I was working on before this one (which I eventually published in PNAS) concerned the probability of evolutionary rescue or resistance, and that work suggests that evolution of new COVID variants reduces significantly when there are fewer infections. So an elimination strategy should also be more robust against the evolution of new variants.

What lessons would you like experts (and the public) to take from this work when considering future pandemic scenarios?

I’d like them to conclude that pandemics with similar properties are, in principle, controllable to small levels of infection – or complete extinction – on timescales of months, not years, and that controlling them minimizes the chance of new variants evolving. So, although the question of the political and social will to enact such an elimination strategy is not in the scope of the paper, I think if epidemiologists, policy experts, politicians and the public understood that lockdowns have a finite time horizon, then it is more likely that this strategy could be adopted in the future.

I should also say that my work makes no comment on the social harms of lockdowns, which shouldn’t be minimized and would need to be weighed against the potential benefits.

What do you plan to do next?

I think the most interesting next avenue will be to develop theory that lets us better understand the stability of the extinct state at the national and global level, under various assumptions about declining infections in other countries that adopted different strategies and the role of an animal reservoir.

It would also be interesting to explore the role of “superspreaders”, or infected individuals who infect many other people. There’s evidence that many infections spread primarily through relatively few superspreaders, and heuristic arguments suggest that taking this into account would decrease the time to extinction compared to the estimates in this paper.

I’ve also had a long-term interest in understanding the evolution of viruses from the lens of what are known as genotype phenotype maps, where we consider the non-trivial and often redundant mapping from genetic sequences to function, where the role of stochasticity in evolution can be described by statistical physics analogies. For the evolution of the antibodies that help us avoid virus antigens, this would be a driven system, and theories of non-equilibrium statistical physics could play a role in answering questions about the evolution of new variants.

The post Staying the course with lockdowns could end future pandemics in months appeared first on Physics World.

The EU Space Act: a call for true strategic fairness

Before we start, a caveat: The following opinion is only relevant in a situation where the EU, together with its member states, would eventually decide to invest enough to equip itself with space capabilities commensurate with Europe’s economic importance, the role it wants to play in the world and current security threats (meaning: significantly more […]

The post The EU Space Act: a call for true strategic fairness appeared first on SpaceNews.

The future is now: understanding the once far-off technologies becoming reality

The technologies pushing the boundaries of the space economy sound as if they came from a science fiction novel: reusable rockets, satellite assembly lines, lunar landers and octocopters. On Nov. […]

The post The future is now: understanding the once far-off technologies becoming reality appeared first on SpaceNews.

When is good enough ‘good enough’?

Whether you’re running a business project, carrying out scientific research, or doing a spot of DIY around the house, knowing when something is “good enough” can be a tough question to answer. To me, “good enough” means something that is fit for purpose. It’s about striking a balance between the effort required to achieve perfection and the cost of not moving forward. It’s an essential mindset when perfection is either not needed or – as is often the case – not attainable.

When striving for good enough, the important thing to focus on is that your outcome should meet expectations, but not massively exceed them. Sounds simple, but how often have we heard people say things like they’re “polishing coal”, striving for “gold plated” or “trying to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear”. It basically means they haven’t understood, defined or even accepted the requirements of the end goal.

Trouble is, as we go through school, college and university, we’re brought up to believe that we should strive for the best in whatever we study. Those with the highest grades, we’re told, will probably get the best opportunities and career openings. Unfortunately, this approach means we think we need to aim for perfection in everything in life, which is not always a good thing.

How to be good enough

So why is aiming for “good enough” a good thing to do? First, there’s the notion of “diminishing returns”. It takes a disproportionate amount of effort to achieve the final, small improvements that most people won’t even notice. Put simply, time can be wasted on unnecessary refinements, as embodied by the 80/20 rule (see box).

The 80/20 rule: the guiding principle of “good enough”

Also known as the Pareto principle – in honour of the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto who first came up with the idea – the 80/20 rule states that for many outcomes, 80% of consequences or results come from 20% of the causes or effort. The principle helps to identify where to prioritize activities to boost productivity and get better results. It is a guideline, and the ratios can vary, but it can be applied to many things in both our professional and personal lives.

Examples from the world of business include the following:

Business sales: 80% of a company’s revenue might come from 20% of its customers.

Company productivity: 80% of your results may come from 20% of your daily tasks.

Software development: 80% of bugs could be caused by 20% of the code.

Quality control: 20% of defects may cause 80% of customer complaints.

Good enough also helps us to focus efforts. When a consumer or customer doesn’t know exactly what they want, or a product development route is uncertain, it can be better to deliver things in small chunks. Providing something basic but usable can be used to solicit feedback to help clarify requirements or make improvements or additions that can be incorporated into the next chunk. This is broadly along the lines of a “minimum viable product”.

Not seeking perfection reminds us too that solutions to problems are often uncertain. If it’s not clear how, or even if, something might work, a proof of concept (PoC) can instead be a good way to try something out. Progress can be made by solving a specific technical challenge, whether via a basic experiment, demonstration or short piece of research. A PoC should help avoid committing significant time and resource to something that will never work.

Aiming for “good enough” naturally leads us to the notion of “continuous improvement”. It’s a personal favourite of mine because it allows for things to be improved incrementally as we learn or get feedback, rather than producing something in one go and then forgetting about it. It helps keep things current and relevant and encourages a culture of constantly looking for a better way to do things.

Finally, when searching for good enough, don’t forget the idea of ballpark estimates. Making approximations sounds too simple to be effective, but sometimes a rough estimate is really all you need. If an approximate guess can inform and guide your next steps or determine whether further action will be necessary then go for it.

The benefits of good enough

Being good enough doesn’t just lead to practical outcomes, it can benefit our personal well-being too. Our time, after all, is a precious commodity and we can’t magically increase this resource. The pursuit of perfection can lead to stagnation, and ultimately burnout, whereas achieving good enough allows us to move on in a timely fashion.

A good-enough approach will even make you less stressed. By getting things done sooner and achieving more, you’ll feel freer and happier about your work even if it means accepting imperfection. Mistakes and errors are inevitable in life, so don’t be afraid to make them; use them as learning opportunities, rather than seeing them as something bad. Remember – the person who never made a mistake never got out of bed.

Recognizing that you’ve done the best you can for now is also crucial for starting new projects and making progress. By accepting good enough you can build momentum, get more things done, and consistently take actions toward achieving your goals.

Finally, good enough is also about shared ownership. By inviting someone else to look at what you’ve done, you can significantly speed up the process. In my own career I’ve often found myself agonising over some obscure detail or feeling something is missing, only to have my quandary solved almost instantly simply by getting someone else involved – making me wish I’d asked them sooner.

Caveats and conclusions

Good enough comes with some caveats. Regulatory or legislative requirements means there will always be projects that have to reach a minimum standard, which will be your top priority. The precise nature of good enough will also depend on whether you’re making stuff (be it cars or computers) or dealing with intangible commodities such as software or services.

So what’s the conclusion? Well, in the interests of my own time, I’ve decided to apply the 80/20 rule and leave it to you to draw your own conclusion. As far as I’m concerned, I think this article has been good enough, but I’m sure you’ll let me know if it hasn’t. Consider it as a minimally viable product that I can update in a future column.

The post When is good enough ‘good enough’? appeared first on Physics World.

Looking for inconsistencies in the fine structure constant

New high-precision laser spectroscopy measurements on thorium-229 nuclei could shed more light on the fine structure constant, which determines the strength of the electromagnetic interaction, say physicists at TU Wien in Austria.

The electromagnetic interaction is one of the four known fundamental forces in nature, with the others being gravity and the strong and weak nuclear forces. Each of these fundamental forces has an interaction constant that describes its strength in comparison with the others. The fine structure constant, α, has a value of approximately 1/137. If it had any other value, charged particles would behave differently, chemical bonding would manifest in another way and light-matter interactions as we know them would not be the same.

“As the name ‘constant’ implies, we assume that these forces are universal and have the same values at all times and everywhere in the universe,” explains study leader Thorsten Schumm from the Institute of Atomic and Subatomic Physics at TU Wien. “However, many modern theories, especially those concerning the nature of dark matter, predict small and slow fluctuations in these constants. Demonstrating a non-constant fine-structure constant would shatter our current understanding of nature, but to do this, we need to be able to measure changes in this constant with extreme precision.”

With thorium spectroscopy, he says, we now have a very sensitive tool to search for such variations.

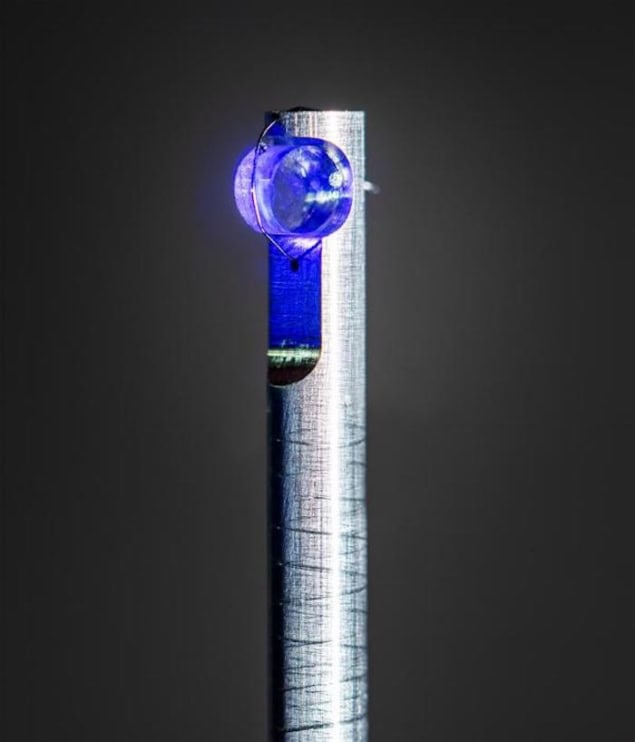

Nucleus becomes slightly more elliptic

The new work builds on a project that led, last year, to the worlds’s first nuclear clock, and is based on precisely determining how the thorium-229 (229Th) nucleus changes shape when one of its neutrons transitions from a ground state to a higher-energy state. “When excited, the 229Th nucleus becomes slightly more elliptic,” Schumm explains. “Although this shape change is small (at the 2% level), it dramatically shifts the contributions of the Coulomb interactions (the repulsion between protons in the nucleus) to the nuclear quantum states.”

The result is a change in the geometry of the 229Th nucleus’ electric field, to a degree that depends very sensitively on the value of the fine structure constant. By precisely observing this thorium transition, it is therefore possible to measure whether the fine-structure constant is actually a constant or whether it varies slightly.

After making crystals of 229Th doped in a CaF2 matrix at TU Wien, the researchers performed the next phase of the experiment in a JILA laboratory at the University of Colorado, Boulder, US, firing ultrashort laser pulses at the crystals. While they did not measure any changes in the fine structure constant, they did succeed in determining how such changes, if they exist, would translate into modifications to the energy of the first nuclear excited state of 229Th.

“It turns out that this change is huge, a factor 6000 larger than in any atomic or molecular system, thanks to the high energy governing the processes inside nuclei,” Schumm says. “This means that we are by a factor of 6000 more sensitive to fine structure variations than previous measurements.”

Increasing the spectroscopic accuracy of the 229Th transition

Researchers in the field have debated the likelihood of such an “enhancement factor” for decades, and theoretical predictions of its value have varied between zero and 10 000. “Having confirmed such a high enhancement factor will now allow us to trigger a ‘hunt’ for the observation of fine structure variations using our approach,” Schumm says.

Andrea Caputo of CERN’s theoretical physics department, who was not involved in this work, calls the experimental result “truly remarkable”, as it probes nuclear structure with a precision that has never been achieved before. However, he adds that the theoretical framework is still lacking. “In a recent work published shortly before this work, my collaborators and I showed that the nuclear-clock enhancement factor K is still subject to substantial theoretical uncertainties,” Caputo says. “Much progress is therefore still required on the theory side to model the nuclear structure reliably.”

Schumm and colleagues are now working on increasing the spectroscopic accuracy of their 229Th transition measurement by another one to two orders of magnitude. “We will then start hunting for fluctuations in the transition energy,” he reveals, “tracing it over time and – through the Earth’s movement around the Sun – space.

The present work is detailed in Nature Communications.

The post Looking for inconsistencies in the fine structure constant appeared first on Physics World.

Japan Rising: Tokyo-Based Axelspace is Making Microsatellites with a Big Impact

Japan is a lion in kittens’ clothing. In both land area and population, it pales in comparison to the likes of the United States, China, India, Brazil, and Russia. In […]

The post Japan Rising: Tokyo-Based Axelspace is Making Microsatellites with a Big Impact appeared first on SpaceNews.

China launches classified Shijian-28 spacecraft, reusable Zhuque-3 rocket faces delay

China launched the latest in a series of experimental, often opaque satellites Sunday, while the debut flight of the commercial Zhuque-3 faces a delay.

The post China launches classified Shijian-28 spacecraft, reusable Zhuque-3 rocket faces delay appeared first on SpaceNews.

China’s Shijian spacecraft separate after pioneering geosynchronous orbit refueling tests

A pair of experimental Shijian satellites have separated in geosynchronous orbit after being docked for months conducting apparent low-profile on-orbit refueling tests.

The post China’s Shijian spacecraft separate after pioneering geosynchronous orbit refueling tests appeared first on SpaceNews.

The Oceans Are Going to Rise—but When?

‘Game changer’: System to track small animals from space takes flight—again

Neptune Is the Furthest Planet From the Sun, But It Still Experiences Auroras

Transporter-15 rideshare mission launches 140 payloads

A Falcon 9 launched 140 payloads on its latest dedicated rideshare mission Nov. 28, ranging from European government spacecraft to a private astronomy satellite.

The post Transporter-15 rideshare mission launches 140 payloads appeared first on SpaceNews.

Baikonur pad damaged in Soyuz launch to ISS

The Baiknour pad used for the launch of the latest crew to the ISS has sustained damage, raising questions about its ability to support upcoming missions to the station.

The post Baikonur pad damaged in Soyuz launch to ISS appeared first on SpaceNews.

Varda Space launches its fifth mission, extends run of AFRL test flights

W-5 is the newest spacecraft in the company’s “W-Series” of free-flying reentry vehicles designed to orbit Earth, conduct on-orbit processing and return space-made materials.

The post Varda Space launches its fifth mission, extends run of AFRL test flights appeared first on SpaceNews.

Antiviral drug abandoned by pharma shows promise against dengue

Think Pterosaurs and Plesiosaurs Are Dinosaurs? Here's Why These and Other Species Are Not

D-Orbit sends to ION vehicles aloft on SpaceX Transporter-15

SAN FRANCISCO – Italy’s D-Orbit sent satellites and hosted payloads into orbit Nov. 26 aboard two ION orbital transfer vehicles launched on SpaceX’s Transporter-15 rideshare. Italy’s first optical intersatellite link (OISL) mission was onboard the IONs alongside payloads from Spire, Spaceium, Pale Blue, Finland’s Aalto University, Planetek and StardustMe. “With these two missions, we cross […]

The post D-Orbit sends to ION vehicles aloft on SpaceX Transporter-15 appeared first on SpaceNews.

China moves to integrate commercial space into its national space development plan

China’s space administration has published a policy blueprint aimed at accelerating development of commercial space and embedding it within its broader national space ambitions.

The post China moves to integrate commercial space into its national space development plan appeared first on SpaceNews.

Even Chihuahuas Still Have Some Wolf in Them — Here’s How Some Dogs Still Carry This DNA

Icy Moons Orbiting Saturn and Uranus May Hide Boiling Liquid Oceans

Volcanic Activity on Mars Could Help in the Search for Life on Other Planets

Heat engine captures energy as Earth cools at night

A new heat engine driven by the temperature difference between Earth’s surface and outer space has been developed by Tristan Deppe and Jeremy Munday at the University of California Davis. In an outdoor trial, the duo showed how their engine could offer a reliable source of renewable energy at night.

While solar cells do a great job of converting the Sun’s energy into electricity, they have one major drawback, as Munday explains: “Lack of power generation at night means that we either need storage, which is expensive, or other forms of energy, which often come from fossil fuel sources.”

One solution is to exploit the fact that the Earth’s surface absorbs heat from the Sun during the day and then radiates some of that energy into space at night. While space has a temperature of around −270° C, the average temperature of Earth’s surface is a balmy 15° C. Together, these two heat reservoirs provide the essential ingredients of a heat engine, which is a device that extracts mechanical work as thermal energy flows from a heat source to a heat sink.

Coupling to space

“At first glance, these two entities appear too far apart to be connected through an engine. However, by radiatively coupling one side of the engine to space, we can achieve the needed temperature difference to drive the engine,” Munday explains.

For the concept to work, the engine must radiate the energy it extracts from the Earth within the atmospheric transparency window. This is a narrow band of infrared wavelengths that pass directly into outer space without being absorbed by the atmosphere.

To demonstrate this concept, Deppe and Munday created a Stirling engine, which operates through the cyclical expansion and contraction of an enclosed gas as it moves between hot and cold ends. In their setup, the ends were aligned vertically, with a pair of plates connecting each end to the corresponding heat reservoir.

For the hot end, an aluminium mount was pressed into soil, transferring the Earth’s ambient heat to the engine’s bottom plate. At the cold end, the researchers attached a black-coated plate that emitted an upward stream of infrared radiation within the transparency window.

Outdoor experiments

In a series of outdoor experiments performed throughout the year, this setup maintained a temperature difference greater than 10° C between the two plates during most months. This was enough to extract more than 400 mW per square metre of mechanical power throughout the night.

“We were able to generate enough power to run a mechanical fan, which could be used for air circulation in greenhouses or residential buildings,” Munday describes. “We also configured the device to produce both mechanical and electrical power simultaneously, which adds to the flexibility of its operation.”

With this promising early demonstration, the researchers now predict that future improvements could enable the system to extract as much as 6 W per square metre under the same conditions. If rolled out commercially, the heat engine could help reduce the reliance of solar power on night-time energy storage – potentially opening a new route to cutting carbon emissions.

The research has described in Science Advances.

The post Heat engine captures energy as Earth cools at night appeared first on Physics World.

How to Measure the Earth’s Radius With Legos