Those Orcas Wearing Salmon Hats? It Might Not Be as Cute as You Think

How well have you been following events in physics? There are 20 questions in total: blue is your current question and white means unanswered, with green and red being right and wrong.

16–20 Top quark – congratulations, you’ve hit Einstein level

11–15 Strong force – good but not quite Nobel standard

6–10 Weak force – better interaction needed

0–5 Bottom quark – not even wrong

The post Check your physics knowledge with our bumper end-of-year quiz appeared first on Physics World.

ZAP-X is a next-generation, cobalt-free, vault-free stereotactic radiosurgery system purpose-built for the brain. Delivering highly precise, non-invasive treatments with exceptionally low whole-brain and whole-body dose, ZAP-X’s gyroscopic beam delivery, refined beam geometry and fully integrated workflow enable state-of-the-art SRS without the burdens of radioactive sources or traditional radiation bunkers.

ZAP-X is a next-generation, cobalt-free, vault-free stereotactic radiosurgery system purpose-built for the brain. Delivering highly precise, non-invasive treatments with exceptionally low whole-brain and whole-body dose, ZAP-X’s gyroscopic beam delivery, refined beam geometry and fully integrated workflow enable state-of-the-art SRS without the burdens of radioactive sources or traditional radiation bunkers.

Theresa Hofman is deputy head of medical physics at the European Radiosurgery Center Munich (ERCM), specializing in stereotactic radiosurgery with the CyberKnife and ZAP‑X systems. She has been part of the ERCM team since 2018 and has extensive clinical experience with ZAP‑X, one of the first centres worldwide to implement the technology in 2021. Since then, the team has treated more than 900 patients with ZAP‑X, and she is deeply involved in both clinical use and evaluation of its planning software.

She holds a master’s degree in physics from Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, where she authored two first‑author publications on range verification in carbon‑ion therapy. At ERCM, she has published additional first‑author studies on CyberKnife kidney‑treatment accuracy and on comparative planning between ZAP‑X and CyberKnife. She is currently conducting further research on the latest ZAP‑X planning software. Her work is driven by the goal of advancing high‑quality radiosurgery and ensuring the best possible treatment for every patient.

The post ZAP-X radiosurgery and ZAP-Axon SRS planning: technology overview, workflow and complex case insights from a leading SRS centre appeared first on Physics World.

An Indian LVM3 rocket launched AST SpaceMobile’s next-generation direct-to-device BlueBird satellite Dec. 23, kicking off a rollout of dozens of spacecraft built around the largest commercial communications antenna ever deployed in LEO.

The post Indian rocket launches AST SpaceMobile’s next-gen BlueBird 6 satellite appeared first on SpaceNews.

MILAN — The European Space Agency announced plans to hire approximately 520 new staff members starting in 2026, following decisions approved at ESA’s 342nd Council meeting earlier this month. The recruitment will result in a net increase of about 400 staff, alongside the replacement of roughly 120 positions due to retirements. The move will bring […]

The post ESA to hire 520 new staff as workforce expansion begins in 2026 appeared first on SpaceNews.

In this episode of Space Minds, host David Ariosto speaks with Juan Alonso — CTO and Co-founder of Luminary Cloud and professor at Stanford University — about the rapid transformation underway in aerospace engineering.

The post How physics AI is transforming the future of space engineering appeared first on SpaceNews.

This episode of the Physics World Weekly podcast features Pat Hanrahan, who studied nuclear engineering and biophysics before becoming a founding employee of Pixar Animation Studios. As well as winning three Academy Awards for his work on computer animation, Hanrahan won the Association for Computing Machinery’s A.M. Turing Award for his contributions to 3D computer graphics, or CGI.

Earlier this year, Hanrahan spoke to Physics World’s Margaret Harris at the Heidelberg Laureate Forum in Germany. He explains how he was introduced to computer graphics by his need to visualize the results of computer simulations of nervous systems. That initial interest led him to Pixar and his development of physically-based rendering, which uses the principles of physics to create realistic images.

Hanrahan explains that light interacts with different materials in very different ways, making detailed animations very challenging. Indeed, he says that creating realistic looking skin is particularly difficult – comparing it to the quest for a grand unified theory in physics.

He also talks about how having a background in physics has helped his career – citing his physicist’s knack for creating good models and then using them to solve problems.

The post Oscar-winning computer scientist on the physics of computer animation appeared first on Physics World.

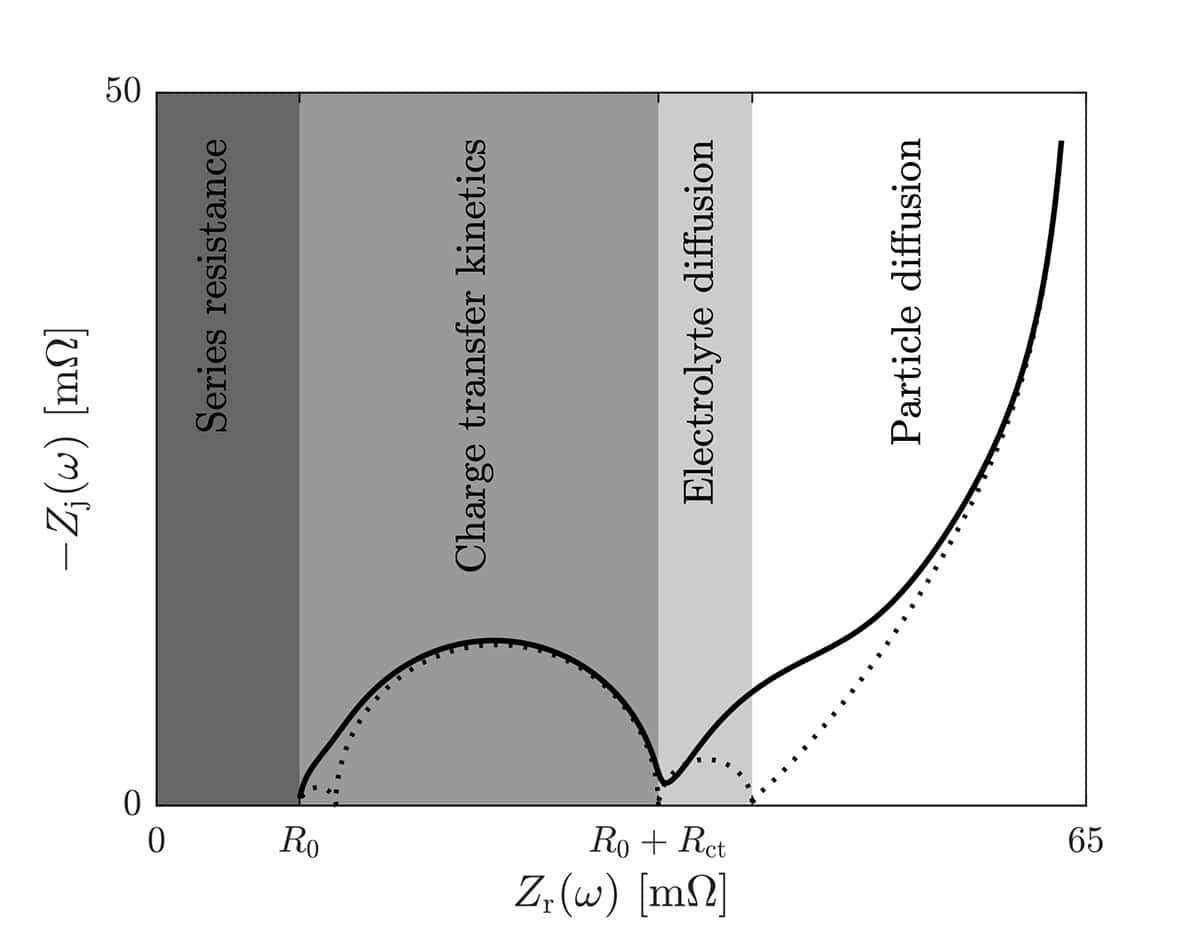

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) provides valuable insights into the physical processes within batteries – but how can these measurements directly inform physics-based models? In this webinar, we present recent work showing how impedance data can be used to extract grouped parameters for physics-based models such as the Doyle–Fuller–Newman (DFN) model or the reduced-order single-particle model with electrolyte (SPMe).

We will introduce PyBaMM (Python Battery Mathematical Modelling), an open-source framework for flexible and efficient battery simulation, and show how our extension, PyBaMM-EIS, enables fast numerical impedance computation for any implemented model at any operating point. We also demonstrate how PyBOP, another open-source tool, performs automated parameter fitting of models using measured impedance data across multiple states of charge.

Battery modelling is challenging, and obtaining accurate fits can be difficult. Our technique offers a flexible way to update model equations and parameterize models using impedance data.

Join us to see how our tools create a smooth path from measurement to model to simulation.

An interactive Q&A session follows the presentation.

Noël Hallemans is a postdoctoral research assistant in engineering science at the University of Oxford, where he previously lectured in mathematics at St Hugh’s College. He earned his PhD in 2023 from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and the University of Warwick, focusing on frequency-domain, data-driven modelling of electrochemical systems.

His research at the Battery Intelligence Lab, led by Professor David Howey, integrates electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) with physics-based modelling to improve understanding and prediction of battery behaviour. He also develops multisine EIS techniques for battery characterisation during operation (for example, charging or relaxation).

The post Physics-based battery model parameterization from impedance data appeared first on Physics World.

A first launch of the Long March 12A Chinese state-owned reusable rocket reached orbit late Monday, but attempted recovery of the first stage downrange failed.

The post Long March 12A reaches orbit in first reusable launch attempt, but landing fails appeared first on SpaceNews.